James Powell

The Shiners' War

20 October 1835

Bytown, the future Ottawa, was a rough place to live during the early nineteenth century. The combination of French, Irish, English, and Scottish settlers was a combustible mixture, especially when combined with religious differences, historic grievances, discrimination, a rigid social structure, poverty, and alcohol. Mother Mcguinty’s Tavern, which was located in Corktown amidst the shanties that lined the Rideau Canal, and Firth’s Tavern close to the Chaudière Falls, were notorious watering holes. If those didn’t suit, there were dozens of other legal taverns as well as illegal grog houses to patronize. Drunken fights and brawls were commonplace, especially when the lumbermen and raftsmen, the workers who brought the cut logs downriver, were in town to gather supplies for the lumbering season.

Despite being co-religionists, Irish and French Canadians often duked it out on the streets of Bytown. Folklore has it that Joseph Montferrand, big Joe Mufferaw to English-speakers, fought off as many as 150 Irishmen in 1829 standing in the middle of the Union Bridge that linked Bytown in Upper Canada to Hull in Lower Canada across the Chaudière Falls. The story has it that Montferrand, a muscular lumberman of considerable proportions, dumped each Irishman who challenged him into the Ottawa River. Montferrand came to be seen as a defender of French rights.

Matters only got worse after the Rideau Canal was completed in 1832 and work became scarce. Unemployed Irish canal workers looked for jobs in the lumber industry, a business hitherto dominated by French Canadians. Tempers flared and fists flew. The Irish gained the upper hand against their French Canadian neighbours when they found a champion who organized them. That leader was Peter Aylen. Of Irish extraction, he was born Peter Vallely in Liverpool, England. He came to Canada in 1815, reportedly after jumping ship at Quebec. At some point he changed his name to Aylen. Little is known about his early years in Canada, but by the 1830s he had become prominent in the lumber business in the Ottawa Valley. Aylen hired only Irish workers, a fact that endeared him to the Irish community in Lower Bytown. He was very successful, becoming a member of the “Gatineau Privilege” who obtained a monopoly to cut timber in the Gatineau River area. He also had lumber operations in the watersheds of the Bonnechere and Madawaska Rivers. In the 1830s, Aylen built a substantial stone homestead on Richmond Road which still stands today.

Aylen’s Irish followers were called Shiners. The origins of the term is obscure. One explanation is that it’s a corruption of the French word chêneurs, or fellers of oak. Another has it that they considered themselves to be the shining ones who stood out above all others. Yet other explanations have them named for the shiny tall hats that newcomers wore, or the shiny silver half-crown coins with which they were paid. Regardless, the Shiners were hooligans who terrorized Bytown and the environs for years. Many offences were laid at their doorstep including stripping children naked in the snow, fouling wells, accosting women in the street and shattering windows. On one occasion, it is said that they broke up a funeral cortege and threw the coffin off the hearse into the street.

They were also accused of serious crimes such as assault, arson, rape and murder. On one occasion, the pregnant wife of a farmer called Hobbs, who had somehow crossed the Shiners, was attacked while driving home in a sleigh with other female members of the family. Beaten with sticks, Mrs Hobbs tried to jump to safety. But her clothing caught in the sleigh and she was dragged over the frozen ground before coming free. The Shiners cut her team of horses loose from the sleigh and ran them off. The next day, the horses managed to find their way home. Their ears and tails had been mutilated.

Peter Aylen’s House, built circa. 1830, 150 Richmond Road, Ottawa. In 1914, the home’s substantial out-buildings were destroyed by fire. July 2018, by James Powell.

Peter Aylen’s House, built circa. 1830, 150 Richmond Road, Ottawa. In 1914, the home’s substantial out-buildings were destroyed by fire. July 2018, by James Powell.

According to the Capuchin priest, Father Alexis de Barbezieux, people said “Il n’y a pas de Dieu à Bytown.” (There is no God in Bytown.) Families without news of children who had gone to Bytown to work in the lumber camps feared that they had been killed. Many years later, some believed that in the middle of the night at the Chaudière Bridge (the bridge that replaced the Union Bridge) you could hear the cries of drowned French-Canadian voyageurs and Irish Shiners, the victims of desperate fights who had fallen to their deaths into the rapids below.

In 1835, Peter Aylen stepped up his campaign to control the lumber industry. Shiners began interdicting timber rafts owned by French Canadians going down the Ottawa River to Montreal. Aylen also had bigger ideas—taking over Bytown. Beatings and intimidation increased on the town’s streets. Special constables that were supposed to keep the peace looked the other way, or were in Aylen’s pay. If pursued, hooligans simply crossed the border into Lower Canada and evaded arrest. Even if they were captured, they had to be transported to Perth for trial as there was no jail or courthouse in Bytown. Poorly paid constables were loath to make the perilous fifty-mile journey given the many opportunities for ambush along the way.

Commemorative Plaque on Peter Aylen’s house, 150 Richmond Road. The home was later owned by the Heney family. July 2018, by James Powell.

Commemorative Plaque on Peter Aylen’s house, 150 Richmond Road. The home was later owned by the Heney family. July 2018, by James Powell.

Despite the anarchy, the community’s wealthy elite in Upper Bytown didn’t take serious action to suppress the Shiners as long as problems were confined to Lower Town. But when the Irish-French feud disrupted the all-important timber trade, and prices rose as farmers became reluctant to bring provisions to lawless Bytown, the town’s merchants woke up to the risks. In August 1835, Peter Aylen challenged the elites politically when he took over the Bathurst District Agricultural Society, the pinnacle of Bytown society life. Drunken Shiners, furnished by Aylen with the necessary one dollar membership fee, overwhelmed authentic members and voted in Aylen and his friends as directors.

With this, Aylen had gone too far. On 20 October 1835, a group of prominent Bytown householders established the Bytown Association for the Preservation of the Peace. They appealed to town magistrates for one hundred guns to arm citizens. Vigilantes made nightly patrols in an attempt to maintain order. As the army based in Barrick Hill was called out only on rare occasions to quell riots, the town formed a volunteer force, the Bytown Rifles, to combat the Shiners. However, the Rifles quickly disintegrated as nobody was willing to serve under its commander, Captain Baker, who was apparently something of a martinet.

Although the vigilantes had some success in keeping the peace, the Shiners continued to terrorize Bytown citizens. In March 1836, the community’s leading lumbermen founded the Ottawa Lumber Association as a further step in suppressing violence in their industry. However, with Aylen as one of its officers, the first act of the new organization was “to improve the movement of timber” on the Madawaska River where Aylen had operations. This likely meant protecting Aylen’s timber interests from angry French Canadians.

In early January 1837, Aylen and his gang disrupted the election of councillors to the Nepean Township Council held in John Stanley’s Tavern in Bytown. While Aylen was elected as one of the three councillors, he demanded that the other two positions be filled with his cronies. A gang of 40-60 of his men, many of whom had arrived at the tavern walking behind a sleigh bearing a portrait of St Patrick, stormed the meeting room, some entering via a broken window. Several of Aylen’s opponents, including James Johnson the founder of The Bytown Independent and Farmer’s Advocate, Bytown’s first newspaper, were violently beaten with sticks and horse whips in the meeting room and in the tavern’s courtyard. Protests that Aylen’s supporters were not Bytown property owners and hence were ineligible to vote went unheeded. The meeting ended in disarray with legitimate attendees fleeing in panic, and the provincial statutes and other important papers destroyed. Order was only restored by intervention of the military.

An official inquiry into the riot was held ten days later by four Bytown magistrates. Most of the dozen or so witnesses who testified blamed Aylen for the affray. Aylen and his cronies did not testify. The magistrates concluded that vigorous measures needed to be adopted to prevent a recurrence of a similar breach of the Peace. They recommended the establishment of a municipal police force and the building of a courthouse and jail in Bytown.

The Bytown Gazette didn’t comment on what it called the “disturbances” until almost eight weeks after the riot at Stanley’s tavern, and only did so with “a good deal of reluctance.” The newspaper cautiously concluded that “our more intelligent readers will doubtless perceive, that a subject of this nature will be viewed in many different lights by different men, that no detail of occurrences with satisfy every one.” It thought there was enough blame to be shared around. “[A]lthough the disturbances have in general been attributed to the Lumbermen, under the cognomen of shiners, there have been instances in which our yeomanry have been the aggressors.” The newspaper also opined that Bytown was being maligned due to the circulation of untrue or exaggerated stories.

Like the magistrates who held the inquiry, the Gazette thought that part of the problem was the lack of a jail. “A wholesome dread of prompt punishment would deter them from committing [crimes].” The newspaper also argued that there were too many unlicensed “Tippling Houses” where men could obtain alcohol. Legal tavern keepers should form an association to stop illegal drinking establishments. This would be an “effectual means of suppressing these hordes of vice from whence so large a portion of these disorders proceed.”

The Gazette stiffened its resolve against the Shiners when in early March 1837 armed men went to the house of James Johnson who had been beaten in the January riot on the pretense of searching for a man. Shots were fired into the upstairs rooms. Fortunately, nobody was hurt. The Gazette fumed that it was “high time measures were adopted to check them.” Poor James Johnson was to suffer yet another attempt on this life a short time later. This time, his three assailants armed with guns and whips nearly succeeded. Ambushed on Sappers’ bridge that linked Upper Town to Lower Town, Johnson had to jump into deep snow to save himself. He was rescued by passersby, but suffered a fractured skull. Fortunately, he recovered.

Unlike in the past when the Shiners could act with impunity, the three men who committed the outrage were captured and taken to Perth to stand trial. Although Aylen broke them out of jail, they were subsequently recaptured in late 1837 and served three years with hard labour in a penitentiary for attempted murder.

By this time, the age of the Shiners was fading. Bytown citizens were themselves becoming better organized and less likely to be cowed. Aylen, who had been charged with a number of offences over the years without any apparent consequence, either sold or rented out his properties on the Upper Canada side of the Ottawa River, and moved to Aylmer on the Lower Canada side. There, he continued in the lumber business. But in Aylmer, he apparently mellowed, becoming a respected member of the community. He even helped to build the area’s first church. He also became a member of the Hull Township Council in 1846, a Justice of the Peace (no joke) in 1848 and the superintendent of roads in the mid-1850s. He died peacefully in 1868.

The Shiners continued to commit acts of violence into the 1840s. But without Peter Aylen at the helm, they faded into history. Ottawa didn’t get a permanent police force until 1863. The Aylen family remained prominent in the Ottawa area. Five generations of Peter Aylen’s descendants have been lawyers, including H. Aldeous Aylen, Peter Aylen’s great grandson, who was appointed to the Supreme Court of Ontario in 1950. In the year 2000, the legal firm of Scott and Aylen, co-founded by the Aylen family almost fifty years earlier, merged with a number of other firms to create Borden Ladner Gervais LLP, now the largest and oldest law firm in Canada with roots going back almost 200 years.

Sources:

Barbezieux, Alexis de, (Father), 1897. Histoire de la Province Ecclesiastique D’Ottawa et la Colonisation dans la Vallée de l’Ottawa, Vol.1, Ottawa : La Cie d’Imprimerie.

Bytown Gazette (The), 1837. “Reported Disturbances in Bytown,” 23 February.

————————–, 1837. “Untitled,” 2 March.

Cross, Michael S, 1973. “The Shiners’ War: Social Violence in the Ottawa Valley in the 1830s,” The Canadian Historical Review, Vol. LIV, No. 1, March, pp. 1-26.

———————, 1976-2018. “Aylen (Vallely), Peter, Dictionary of Canadian Biography,” http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/aylen_peter_9E.html.

Globe and Mail (The), 2000, “Five law firms wed in cross-country mega-merger, 29 February.

House of Assembly of Upper Canada, 1837. Journal, 1st Session of the 13th Provincial Parliament, Session 1836-37, No. 52 Letter from Magistrates to Mr. Secretary Joseph on the subject of the Bytown Riots, 12 January, W.J. Coates, Printer: Toronto.

———————————————, 1837. “No. 58, Report of the Select Committee on Message of his Excellency the Lieutenant Governor and Documents relative to the Riots at Bytown.” 18 February.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 2014. “John Gordon Aylen, Obituary,” 29 December.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1936. “Christmas In Ottawa One Hundred Years Ago, 19 December.

————————–, 1950. “Name H. Aldous Aylen Supreme Court Justice,” 13 September.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa's Champion Hose Reel Team

2 October 1880

The crowds had started to gather at the train station hours ahead of the arrival of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa Railway train from Prescott, anxious to get a glimpse of their “boys.” On board was the Chaudière No. 1 Hose Reel team, the newly crowned “Champions of America” who were returning from an international meet held in the small town of Malone in upstate New York.

Arriving at 6.30 pm, the team was met by an official welcoming committee that included Fire Chief William Young, head of the Ottawa Fire Brigade. At that time, the Brigade consisted of eighteen professional fire fighters located in five stations, each equipped with a two-wheeled hose reels that could be pulled by one horse, or manually if necessary. Also present were Aldermen Lauzon, Coleman and Heney. Outside of the train station, a hook and ladder truck along with No. 1, 2 and 3 hose reels were drawn up in preparation for the parade through the streets of Ottawa. After the customary greetings, a procession formed up, starting with the team’s reel which was decorated with flags and bore a banner strung between two brooms with the word “Champion” written on it. The time being long past sunset, the parade was lit by torches. On their route to the City Hall on Elgin Street, the “boys” were cheered by crowds of Ottawa residents and supporters.

At City Hall, in the absence of the Mayor, Alderman Lauzon welcomed back the champion hose real team of America. He said that after the team’s earlier defeats at Canton and Potsdam, New York, the victory showed what perseverance can accomplish. The victory was being “hailed with pleasure throughout the Dominion.” Alderman Coleman remarked that the win “added another to the long list of trophies won by Ottawa representatives.” Somewhat more tangibly, Alderman Heney promised that as soon as the City was in better financial shape, the fire brigade would get a pay raise.

Hose reel racing was a very popular activity during the late nineteenth century, with competitions organized among fire departments across North America. Agricultural shows often hosted hose reel races, offering significant prize purses to attract the best teams. With serious money to be had, team members were often professionals selected for their speed or brawn to represent a particular fire hall rather than true fire fighters. Betting on these races was fierce.

In a typical hose reel race, a team of up to 18 men competed to draw a 450-pound reel cart carrying 350 feet of hose yards to a fire hydrant. They would then attach and lay 300 feet of hose, break the couplings and screw on a nozzle. Typically, a total of 400 yards would be run from start to finish. The races were timed. A good team could complete the course in a minute or less. Sometimes, two or more teams would race side by side. In early competitions, a team would push the hose reel cart along the track by hand. In later events, the men were tied to the carts, allowing them to put their entire bodies into the push, leaving their arms free. This was a dangerous sport. If a team member couldn’t keep up, he risked falling and being trampled by his team mates or run over by the hose reel cart. Serious injury could result.

The Chaudière Hose Reel Team, Champions of America, 1880, Topley Studio. Back Row: Cyrille Crappin, W. Cousens, Peter Duffy, “Boston” Ed O’Brien, W. McCullough; Middle Row: Andy Lascelles, Sam Cassidy, Chief William Young, Johnnie Shea; Front Row: J. Newton, Johnnie Raine, and Bob Raine. Missing: W. Grand, B. Leggo, W. Palen, and F. McKnight. Ottawa Citizen, 25 February 1925.

The Chaudière Hose Reel Team, Champions of America, 1880, Topley Studio. Back Row: Cyrille Crappin, W. Cousens, Peter Duffy, “Boston” Ed O’Brien, W. McCullough; Middle Row: Andy Lascelles, Sam Cassidy, Chief William Young, Johnnie Shea; Front Row: J. Newton, Johnnie Raine, and Bob Raine. Missing: W. Grand, B. Leggo, W. Palen, and F. McKnight. Ottawa Citizen, 25 February 1925.

The Chaudière Hose Reel team was formed in LeBreton Flats in 1880. There were in fact at least two hose real teams in Ottawa at this time. At the Fourth Annual Fireman’s Picnic held in early August of that year, the Chaudière Hose Reel team faced the Union Company Hose Real Team which was captained by Cyrille Crappin, a legitimate fire fighter, who belonged to the “Queen Company” stationed at the Nicholas Street Station. At the Fireman’s picnic, organizers had expected that hose real teams from Prescott and Ogdensburg to compete in the same event. But at the last moment, both teams pulled out leaving only the two Ottawa teams in competition. The Chaudière team won the $75 first prize, with the Union team taking home the $30 second prize. Divided among the participants the prizes didn’t amount to much, though it was nice pocket money. This was about to change.

After that early August competition, Crappin joined the Chaudière team. Already a fast team with all its members noted runners—Peter Duffy reportedly ran the 100-yard dash in 9 4/5 seconds—the addition of Crappin took the Chaudières to a new level. He had competed in a number of professional foot races over the previous several years, invariably winning. Most famously, he had defeated a field of a dozen competitors from Montreal, Toronto and the Mohawk First Nation of Caughnawaga in a four-day racing event. Race participants ran continuously for four hours for four consecutive days. Whoever ran the furthest won the competition. The race took place in Powell’s Grove on Bank Street, opposite the Muchmor race track. The hotel located in the Grove sponsored the race. Crappin emerged the victor, having run 119 miles.

With the extra speed and endurance brought by Crappin, the Chaudière Hose Reel team was ready to take on all challengers. Chief Young of the Ottawa Fire Brigade said that he had “from $100 to $1,000 that says that Ottawa can produce a hose reel team…that can beat, and make better time than any hose reel team belonging to any part of the Dominion of Canada.” In September 1880, representatives of the St. Lawrence County Agricultural Society of Canton, New York, who had heard of the Chaudières’ prowess, came to Ottawa to invite the team to compete in Canton’s upcoming hose reel meet. The purse was US$250—a considerable sum of money in those days, equivalent to over US$6,000 today. The Chaudières came in second at the Canton competition behind the Relief Company of Plattsburgh, New York. A few days later, at another meet in Potsdam, New York, the same thing occurred—the Chaudières fell short against the first-place Relief squad. According to hose reel race aficionados, while the team had the necessary speed to win, it lacked an expert coupler. This deficiency was filled by Johnnie Shea who became the new captain of the Chaudière Hose Reel team. Shea hailed from Burlington, Vermont where he had been the coupler for the renowned Barnes Hose Reel team. At Postdam, he asked if he could join the Chaudière team.

After their return to Ottawa with Shea, the Chaudière Hose Reel team practiced on Parliament Hill in front of a large crowd of onlookers and fans to prepare themselves for their next competition to be held in Malone, New York. This time, the purse totalled $450, of which $225 went to the winning team. The Ottawa team arrived two days ahead of the competition which was held on Friday, 1 October on the track of the Franklin County Agricultural Society. They had to borrow all their equipment—the reel from the Blake Hose Company of Swanton, NY, couplings from Chief Engineer Drew of Burlington, Vermont, and the hose from the Blake Hose Company and the Frontier Hose Company of St. Albans, Vermont.

The Ottawa team was met at the Malone train station by the Chief Engineer of the Malone Fire Department and members of the Active Hose Company of Malone. Owing to their late arrival, all the restaurants in the town were closed. Fortunately, the foreman of the Active Hose Company supplied an excellent meal to the hungry Chaudière team who stayed at Hogle House hotel. Owing to rain the next day, the team practiced indoors in a rink. Prior to their arrival, betting had strongly favoured the Relief team. However, once it was known who was on the Chaudière team, the odds shifted heavily in favour of the Ottawa team.

At 10 am Friday morning, six hose reel teams formed up in order of their turn to race—Chaudière Company No.1 of Ottawa, Blake Hose Company of Swanton, NY, the Relief Company No. 2 of Plattsburgh, NY, Washington No. 1 of St. Albans, Vermont, Chamberlin No. 1 of Canton, NY, and the Frontier No.2 of St. Albans, Vermont. The Chaudières and Reliefs came in first tied at 59¼ seconds, necessitating a tie-breaking run. The Ottawa team offered to run the tie-off as a direct race against the Relief squad instead of against the clock. But the Plattsburgh team declined. Betting odds were 2 to 1 on the Ottawa team.

There was considerable excitement among the 8,000 spectators as they waited for the drop of the umpire’s flag. As the Chaudières raced to the finish line, disaster almost happened. A boy who had been running alongside the Ottawa team was apparently pushed “violently” by one of the Relief’s team members into the way of the Ottawa team nearly tripping one of the members. The Ottawa Citizen reported that “fortunately this despicable action did not accomplish what was evidently intended.” Instead, at the finish line, “Shea caught the coupling as it came over the reel…and broke it in a twinkling, with a team member quickly screwing the pipe on “in a masterly and satisfactory manner.” Their time was a phenomenal 58 seconds, easily out classing the Relief Company team who ran next. To great cheers, the Ottawa team drew their reel through the streets of Malone to their hotel. It was reported that the team “carried brooms to show that they had swept the day and also a rake to show the had racked in the cash.”

After their victorious return to Ottawa. Mr. Topley of Topley Studios took the team’s picture in their “full running costume.” Topley had planned to take the picture outside on Parliament Hill, the site of the practice runs. However, inclement weather forced him to take the photograph inside.

The Chaudière Hose Reel team competed the following year in Malone, and won their second American championship, again against the Relief Company of Plattsburgh, NY, taking home the $225 first prize. As a follow-up, the team was slated to race side-by-side with the Wentworth Hose Reel Team of Malone for a $100 prize. Controversially, the Malone team refused to race unless the course was shortened from 400 yards to 300 yards, citing an implicit agreement. The judges ruled against Malone. With the Wentworth Hose Reel team still refusing to run, the $100 was awarded to the Chaudière team. Subsequently, the Franklin Gazette, the Malone newspaper, reported that the Wentworth team was disbanded for their unsporting behaviour.

The success of the Chaudière Hose Reel team may have gone to members’ heads. The Montreal Gazette reported that the team was not willing to compete in any tournament where first prize money was less than $500. By 1882, the Chaudière Hose Reel team appears to have disbanded. In August of that year, Cyrille Crappin, the running star who had helped to bring victory to the Chaudière team in 1880 and 1881, was once again part of the Union Hose Reel Team that was competing in a race for a prize of only $50. There was no mention of the great coupler, Johnnie Shea.

Sources:

Franklin Gazette (Malone), as reprinted in The Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1881. “Hose Reel Racing,” 8 October.

Malone Palladium, as re-printed in The Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1880. “Hose Reel Contests,” 9 October.

Montreal Gazette (The), 1880. “Dominion News, From Ottawa, 3 August.

—————————-, 1880. “Dominion News, From Ottawa,” 24 September.

—————————-, 1880. “Dominion News, From Ottawa,” 28 September.

—————————-, 1881. “Dominion News, From Ottawa,” 16 August.

Ottawa Daily Citizen (The), 1880. “The Firemen’s Picnic,” 6 August.

———————————, 1880. “A Champion Fire Brigade,” 13 August.

———————————, 1880. “The Chaudiere Hose Reel Team,” 28 September.

———————————, 1880. “Return of the Victors,” 4 October.

———————————, 1880. “Photographed,” 5 October.

———————————, 1881. “Hose Reel Competition,” 28 September.

———————————, 1925. “These Were Champions of Champions,” 28 February.

———————————, 1925. “Cyrille Crappin Brought Home The Bacon; Wonderful Distance Runner Of Seventies; Won a Great Victory in Sixteen Hour Race,” 28 February.

———————————, 1925. “Great Pete Duffy In Action,” 25 April.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Great Farini Crosses the Chaudière Falls

9 September 1864

Back in the mid-nineteenth century, the world was wowed by Jean François Gravelet, better known as the Great Blondin. In June 1859, in front of a crowd of 25,000 fascinated and horrified onlookers, Blondin crossed the Niagara Gorge from the United States to Canada on a tightrope. On his return trip, he brought a daguerreotype camera with him to take a photo of the spectators.

One of Blondin’s greatest fans was a young man from Port Hope, Ontario named William Leonard Hunt. Hunt was born in June 1838 in Lockport, New York but grew up close to Port Hope where his parents settled after living for a time in the United States. As a child, he was a daredevil and was fascinated with all things related to the circus—much to his parents’ chagrin who view such activities as dishonourable. Hunt gave his first professional performance as a funambulist (tightrope walker) at age twenty-one by crossing the Ganaraska River in Port Hope on a rope stretched eighty feet high between two buildings, just months after Blondin’s conquest of Niagara Falls. Hunt chose the stage name Signor Guillermo (Italian for William) Farini, or the “Great Farini.”

The Great Farini challenged Blondin to a battle of who would be considered the greatest tightrope walker in the world. Signor Farini matched his idol’s feat by crossing the Niagara Gorge in June 1860. He topped off his performance by hanging from the rope mid-river by one hand, then suspending himself by just his feet. On a subsequent trip, after securing his pole, he climbed down a rope to the tourist boat Maid of the Mist circling below in the Niagara River, drank a glass of wine, and then climbed back up to finish his journey across the Gorge.

The rivalry of the two men took off. Blondin walked across the Falls with his feet in bushel baskets, pushed his manager in a wheel barrow, and even cooked omelettes on a portable stove high above the whirlpools, which he lowered to sightseers on the Maid of the Mist below. Farini responded by carrying his much larger manager across the Falls. Mid-river, Farini somehow unloaded his manager onto the rope, crawled on the underside of the rope beneath his friend to emerge on the other side, and then reloaded him onto his back before finishing the crossing. (Where do you find friends like this?!) Subsequently, Farini washed hankies mid-river using an Empire Washing Machine that he had brought with him across the high wire.

Needless to say, Farini was a sensation. It helped that he was darkly handsome, muscular, with brilliant blue eyes and slicked back black hair. He also worn a goatee with a waxed moustache that extended horizontally several inches on either side of his nose in a style popularized by France’s Napoleon III. He was also extremely articulate and spoke several languages.

After a brief stint in the Union Army in the United States during the American Civil War where he rose to the rank of Captain in the Engineers, he returned to the circus. While performing with his first wife, Mary, in a high wire act above the Plaza de Toros in Havana, Cuba in December 1862, tragedy struck. On their fifth crossing with his wife on his back, Mary unexpectedly waved to cheering spectators. Losing her balance, she fell. Somehow, Farini managed to grab her costume as she tumbled past him, but it was not enough. The fabric ripped and she fell sixty feet in front of a horrified crowd of 15,000 people. She died a few days later.

This catastrophe did not stop his high-wire career. In 1864, he came to Ottawa, which was then in the news owing to negotiations underway in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island among the British colonies in North America on Confederation. If those negotiations were successful, Ottawa would become the capital of a large new nation.

The Chaudière Falls with the Union Suspension Bridge on the right.

The Chaudière Falls with the Union Suspension Bridge on the right.

Circa 1869, Topley Studio, Library and Archives Canada, PA-102695According to Shane Peacock, the author of the definitive biography of the famed tightrope walker, Farini arrived in Ottawa in mid-August, 1864, booking into the Russell House, Ottawa’s premier hotel at the time. His first job was to suss out a likely spot for a high-wire act. He initially thought of crossing the Rideau Canal on a rope strung from Barrick Hill, where the new Parliament buildings were still under construction, to a tower located in what is now Major’s Hill Park. Deciding that such a route was insufficiently death-defying, he chose instead to cross the Ottawa River above the Chaudière Falls. Back in those days, the Chaudière Falls were not the tamed affair they are now but a raging torrent. The Ring Dam that regulates the flow of water over the Falls for the purpose of generating hydro-electricity would not be built for another fifty years. The only way over them at that time, and the only way between Ottawa and Hull, was the Union Suspension Bridge built in 1843. This bridge was later replaced by today’s Chaudière Bridge.

In the days prior to his much advertised crossing, set for Friday, 9 September 1864, work began on suspending a two-inch diameter rope from two heavily-braced wooden towers, one on Table Rock on the Quebec side of the Ottawa River, a short distance upstream from the Union Suspension Bridge, and the other on the Booth lumber mill on Chaudière Island on the Ontario side. The rope was advertised as being 1,000 feet long and 100 feet high. Messrs Perley and Booth along with other mill owners constructed a private viewing stand complete with comfortable seats for the pleasure of Ottawa’s elite. Cost was 25 cents per seat with access to the site provided through the Perley & Company Mill and Brewery or through Mr Booth’s new mill. The general public could watch for free from other vantage points.

The Chaudière Falls stunt wasn’t the only performance planned for Ottawa by the Great Farini. On the Wednesday before his aerial show, Farini gave a charity performance in aid of the new General Hospital, “putting his acrobatic skills at the disposal of the Sisters of Charity.” On the day of his crossing, he also performed at the Theatre Royal where he again demonstrated his gymnastic virtuosity as well as his circus tricks, including the flying trapeze and placing a 400-pound stone on his chest and having somebody smash it with an 18-pound sledge hammer. He also held a man up at arm’s length, a feat that had previously earned him a silver medal from New York gymnasts.

The J.R. Booth Lumber Mill, Chaudière Island, where Farini started his crossing of the Ottawa River. The Prince of Wales Bridge, built in 1880, is in the background.

The J.R. Booth Lumber Mill, Chaudière Island, where Farini started his crossing of the Ottawa River. The Prince of Wales Bridge, built in 1880, is in the background.

Late 19th century, William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, PA-012377.As you can imagine, there was a lot of press hype for Senior Farini’s death-defying tight rope act across the Ottawa River. Half-price trains and excursion boats ran on the Friday of his performance. A special train brought up U.S. spectators from Ogdensburg, New York with extra ferries laid on to take them across the St Lawrence River to meet a special train leaving Prescott for Ottawa at 8am and to return late that night. The Ogdensburg Advance wrote that Farini was “said to excel the great Blondin, not only in hazardous undertakings, by in ease and grace of their accomplishment.” The newspaper also put a plug in for the Russell Hotel saying that its proprietor, “our friend Gouin,” was “always alive to the comfort and convenience of the public,” and dispensed services that “epicures most delight in.” It added that the Russell House ranked among the finest hotels in Canada, and urged excursionists going to Ottawa to “drop in at the Russell House and ‘smile.’”

Monsieur Gouin, of course, hoped they would do more than smile. He advertised first class rooms at only “$4 US currency per day” for visitors to Ottawa to watch Farini cross the Chaudière Falls. This was a real bargain. With the United States in the midst of its Civil War, US$4 was worth much less in Canadian dollar terms. (In mid-July 1864, the U.S. dollar, which was off the gold standard, touched an all-time low against its Canadian counterpart of US$2.78 to one Canadian dollar.) Of course, visitors could also find the best food and drink at the Russell House.

Friday, 9 September 1864 was a perfect day for Farini’s crossings of the Ottawa River. Two performances were organized, with the first beginning at 3pm and the second at 9 pm after his show at the Theatre Royal. Some 15,000 people turned out to watch. Given that the population of Ottawa was less than 15,000 in the 1861 census this is a remarkable number of people, even allowing for population growth and visitors. One of the best vantage points was on the Union Suspension Bridge. However, fearing an accident given the number of people crowding on to it, the bridge keeper closed the gates leading from the Ottawa side.

Advertisement for the Great Farini.

Advertisement for the Great Farini.

The Ottawa Citizen, 6 September 1864Spectators were not disappointed. Farini put on a masterful show. Dressed like a circus acrobat, Farini crossed the Chaudière Falls three times during the one hour-long afternoon show. He crossed with and without a pole, did acrobatics, and hanged upside down from his feet over the raging water. On his second trip, he wore wooden bushel baskets typically used for measuring oats on his feet. For a finale, he crossed in a sack.

As Farini was performing, he was almost upstaged by a young boy, no more than eleven years of age, who managed to climb around a fence that jutted out over the fast-flowing river and cordoned off the eastern side of the reserved area at the Perely and Booth mills. When spectators finally saw what the lad was doing, many rushed over to pull him to safety. But before they could do so, he swung himself around the end of the fence, dangling temporarily over the rapids, before pulling himself to safety and disappearing into the milling crowd.

After talking to the press and well-wishers at the Russell Hotel following his afternoon performance, and giving his evening show at the Theatre Royal—tickets were 25 cents each—Farini repeated his Chaudière Falls crossings at 9pm. As it was well past sunset, he performed to the light of fire-works. According to Shane Peacock, he cut short the evening performance at the request of Ottawa authorities who feared an accident owing to the press of the crowds.

Farini left Ottawa shortly afterwards to perform in Montreal; he never returned. By 1866, he had begun regular performances in England with a young boy, Samuel Wasgatt, whom he later adopted. Called El Niño (the child), young Sam and Farini performed as The Flying Farinis. When El Niño got a bit older, he began performing aerial acrobatics as a woman with long blond hair under the stage name “The Beautiful Lulu, the Circassian Catapultist.” He wasn’t “outed” as a man until 1878.

By this time, the elder Farini, had married an English girl, Alice Carpenter, and had retired his leotards in favour of managing celebrity performers and developing new circus tricks, including the first human cannonball act. For a time, he partnered with the famed P.T. Barnum assembling human oddities, included Krao, a hairy Laotian girl who Farini advertised as The Missing Link. He later adopted the girl. During the mid-1880s, the now divorced Hunt, accompanied by his son Sam, the former Lulu, trekked through southern Africa where they claimed to have discovered the Lost Kingdom of the Kalahari. Photographs taken by Sam and a paper written by Farini, which he presented at the Royal Geographic Society in London, caused a sensation…and sparked a decades’ long quest by explorers. Reportedly, some twenty-five expeditions were launched to find the fabled kingdom which stubbornly remained lost.

In 1886, he married his third wife, German-born Anna Mueller. A man of many parts, he took up horticulture, writing books on New Zealand ferns, and begonias. He later began to paint. In the early 1900s, he and his wife moved back to Canada from England. In Toronto, he apparently dabbled in the stock market, and was involved in a gold mining company. He was also an inventor of some renown, including, among other things, folding theatre seats. Moving to Germany in 1909, Farini spent World War I in that country where he wrote a multi-volume account of the war from a German perspective. In 1920, Farini and his wife returned to North America. After moving around a bit, the couple settled down in Farini’s home town of Port Hope, where he died of the flu in 1929 at the ripe old age of 90.

Sources:

Itchy Feet, Itchy Mind, 2014. The Great Farini, Lulu Farini, And The Lost City Of The Kalahari, 2014, https://itchyfeetandmore.com/2014/12/16/the-farinis-and-the-kalahari-lost-city/.

Ottawa Citizen, 1864. “Signor Farini performing at Theatre Royal,” 9 September.

——————, 1864. “Signor Farini,” 6 September.

——————, 1864, “No title,” 7 October.

Ottawa Journal, 1931. “Signor Farini was a Great Rope Man,” 31 October.

——————, 1950. “340 Years of History Flowed by Chaudiere,” 17 June.

Peacock, Shane, 1995. The Great Farini: The Hire-Wire Life OF William Hunt,” Viking: Toronto.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa's Greatest Store

6 September 1870

Sparks Street used to be the beating heart of Ottawa commerce, home to several major local department stores that had their roots in the late nineteenth century. These included L. N. Poulin’s Dry Goods store, R.J. Devlin & Company, Murphy-Gamble, and Bryson, Graham Ltd. One by one they disappeared into history. Most were bought out by larger chain stores before they too succumbed as shoppers flocked to exciting new suburban shopping centres with ample parking facilities that were closer to where people lived. But back during the early twentieth century when Sparks Street was at its zenith, the place to shop was Bryson, Graham Ltd, then known as “Ottawa’s Greatest Store.”

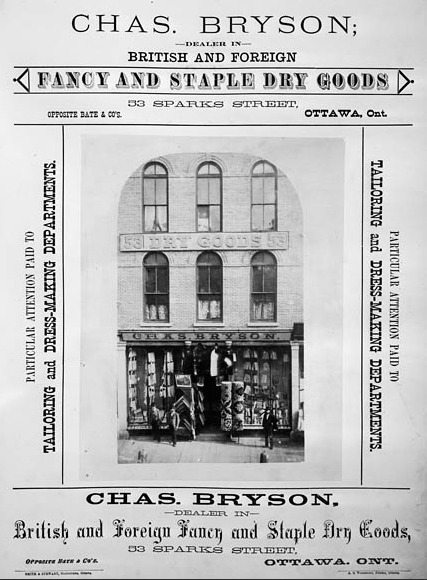

Charles Bryson’s Dry Goods Store, 53 Sparks Street, 1875, William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, PA-002237.It opened for business on 6 September 1870 as Patterson & Bryson at 53 Sparks Street on the south side of the Street (later renumbered as 110 Sparks Street). The firm was named after its two principals, Joseph H. Patterson and Charles B. Bryson. Initially, there wasn’t much going for the modest dry-goods business. With the main commercial streets in Ottawa at that time being Rideau, Sussex and Wellington, the store had an unpromising location. Business was tough during those early years. Indeed, in 1873, the partnership ended, with Patterson decamping to New York City to establish a dry goods business there. Bryson, a country boy from Richmond who had come to Ottawa in 1864 and learnt the dry-good business working at the firm T. Hunt & Sons, soldiered on alone. The split-up appeared to have been relatively amicable, or at least any hard feelings healed over time. On the firm’s silver anniversary in 1895, Patterson sent Bryson from New York a souvenir of their first day in business. Concealed inside twenty-five nested envelopes was the first 5-cent piece the store took in. On one side was engraved “P & B” with “6th Sept., 1870” inscribed on the other.

Charles Bryson’s Dry Goods Store, 53 Sparks Street, 1875, William James Topley, Library and Archives Canada, PA-002237.It opened for business on 6 September 1870 as Patterson & Bryson at 53 Sparks Street on the south side of the Street (later renumbered as 110 Sparks Street). The firm was named after its two principals, Joseph H. Patterson and Charles B. Bryson. Initially, there wasn’t much going for the modest dry-goods business. With the main commercial streets in Ottawa at that time being Rideau, Sussex and Wellington, the store had an unpromising location. Business was tough during those early years. Indeed, in 1873, the partnership ended, with Patterson decamping to New York City to establish a dry goods business there. Bryson, a country boy from Richmond who had come to Ottawa in 1864 and learnt the dry-good business working at the firm T. Hunt & Sons, soldiered on alone. The split-up appeared to have been relatively amicable, or at least any hard feelings healed over time. On the firm’s silver anniversary in 1895, Patterson sent Bryson from New York a souvenir of their first day in business. Concealed inside twenty-five nested envelopes was the first 5-cent piece the store took in. On one side was engraved “P & B” with “6th Sept., 1870” inscribed on the other.

Things began to pick up in the 1880s after Bryson welcomed Frederick Graham into the business which by this point had moved to 152 Sparks Street. Like his colleague, Graham was a country boy. He had come to Ottawa to sell agricultural equipment for William Arnold on Wellington Street. Dissatisfied with his career choice, he joined Bryson in 1880 and very quickly proved his worth. After only a year, he was offered a piece of the business and became a junior partner. Bryson, Graham & Company was born. It was a partnership that was to last close to fifty years. Bryson took charge of the management of the company while Graham took responsibility for buying. In 1882, Graham became part of the family as well, marrying Miss Margaret Bryson, Charles Bryson’s sister.

During the early 1880s, the duo introduced a radical innovation to Ottawa—“One Price for All.” Hitherto, Ottawa residents haggled with merchants for all their purchases, a process that wasted valuable time and typically left somebody dissatisfied. At the same time, Bryson and Graham advertised “Maximum Value for the Money.” Initially, this novel approach to selling cost the partners business, but the general public quickly caught on.

In one possibly apocryphal story set sometime in the 1880s, ten lumbermen entered Bryson Graham to purchase their gear for the coming logging season. They picked out goods worth $650, a very large sum back in those days. The foreman offered to pay $600. The salesman refused. The foreman then asked if he would throw in a vest for each of the workers. Again, the salesman refused. A pair of braces? Again, the answer was no. The group left the store in a huff, repairing to “The Brunswick” for a drink. They later came back, their leader indicating that they would pay the $650 if the salesman threw in a collar button for each of the men. Again, the salesman refused. When called over, Bryson backed up his salesman and explained the store’s pricing policy to the lumbermen. Giving up and paying the full amount, the foreman admitted that he had bet $10 that he could beat down the store. He added that “it was worth more than $10 to find there is one honest price store in Ottawa.”

The reputation of Bryson and Graham for integrity and straight dealing was the backbone of their company. Over the next fifty years, the company prospered mightily. In 1883, the company expanded eastward, leasing the adjoining store. In 1887, the firm added home furnishings when it acquired the stock and premises of Shouldbred & Company, followed by the acquisition of the stock of dress-goods and silks from Mr John Garland. In 1890, John Bryson, the brother of Charles opened a grocery store in the Bryson-Graham premises. This business was later formally consolidated into the family enterprise. This was a gutsy step. The grocery business in Ottawa had previously been an albatross for other department stores. In 1892, the firm bought the china and crockery business of Mr Sam Ashfield in the neighbouring store. Two years later, the company expanded yet again and acquired the entire block when it took over the corset business of yet another neighbour, Mrs Scott. On their silver anniversary in 1895, the firm built a factory extension to Queen Street.

To mark twenty-five years of progress and expansion, the store’s staff gave Charles Bryson a gold-mounted ebony cane. They also presented a testimonial to their boss reading “…under your control, we are happy to labour, and hope that our constant efforts and devotion to business will meet with your appreciation. With great pleasure do we take this opportunity to congratulate you on your past success, and to say that we are proud to see your business house classed amongst the most important and successful houses of the Dominion.”

Innovations and expansion continued during the store’s second twenty-five years. In 1898, Bryson, Graham & Company was the first in Ottawa to use the “comptometer,” the first successful, key-driven, calculating machine. It was used for adding and calculating work, sales checks, statements and invoicing. In 1909, the partnership was transformed into a limited liability company. Two years later, the company erected a large warehouse on Queen Street to store its extensive inventory.

Cover to the Special Supplement in Celebration of Bryson-Graham’s Golden Anniversary, The Ottawa Citizen, 28 February 1920.In 1917, the long and successful partnership of Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham came to an end with the former’s death. Graham became the company’s president, with Mr James B. Bryson, the son of Charles, as vice-president. In 1920, the Ottawa Citizen newspaper celebrated the golden anniversary of the company with a supplement dedicated exclusively to the department store, its history, and its successes. The newspaper opined that the secret of the retailer’s success was the character of Charles Bryson—“his untiring efforts, his forceful personality and his integrity.” The paper also re-published his obituary that stated that Bryson “was a gentleman in business as in his private life; a kind employer, a devoted friend, a real Christian.” The newspaper stated that the many friends of “Ottawa’s Greatest Store” hoped that “the next fifty years will witness an expansion proportionate to that of those gone by.”

Cover to the Special Supplement in Celebration of Bryson-Graham’s Golden Anniversary, The Ottawa Citizen, 28 February 1920.In 1917, the long and successful partnership of Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham came to an end with the former’s death. Graham became the company’s president, with Mr James B. Bryson, the son of Charles, as vice-president. In 1920, the Ottawa Citizen newspaper celebrated the golden anniversary of the company with a supplement dedicated exclusively to the department store, its history, and its successes. The newspaper opined that the secret of the retailer’s success was the character of Charles Bryson—“his untiring efforts, his forceful personality and his integrity.” The paper also re-published his obituary that stated that Bryson “was a gentleman in business as in his private life; a kind employer, a devoted friend, a real Christian.” The newspaper stated that the many friends of “Ottawa’s Greatest Store” hoped that “the next fifty years will witness an expansion proportionate to that of those gone by.”

This wish was not granted. Three years later, in 1923, Frederick Graham died, and the venerable company on Sparks Street passed fully into the hands of the next generation of Brysons and Grahams. James Bryson took over as president and W.M. Graham stepped into the vice-president’s position. For a time, Bryson-Graham continued to do well, but its years of expansion were over. It had apparently transitioned into a comfortable middle age. While it continued to provide a wide range of quality goods to Ottawa customers at reasonable prices, the drive and determination of its founders were gone.

Bryson-Graham’s Last Advertisement, The Ottawa Journal, 17 April 1953Business suffered through the lean years of the Depression and World War II. By the late 1940s, the company was dowdy and old fashioned. In May 1950, Ormie A. Awrey, who had been vice-president and general manager of the firm for the previous eleven years acquired control of the business from the children of the late Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham, buying 85 per cent of the company for $1 million. He later bought the remaining shares. Awrey promised to carry on the traditions of the old firm, but the retailer continued to decline. Parts of the old building were rented out to other retailers, including Bata Shoes, Swears and Wells, and Dolcis. In February 1953, he sold the Bryson-Graham block in February 1953 to J. B. and Archie Dover of Dover’s Ltd for only $310,000. After holding a clearance sale of its stock and fittings, Bryson-Graham, now billed as “Ottawa’s Oldest Department Store,” closed for good on 18 April 1953, ending an 83-year presence on Sparks Street.

Bryson-Graham’s Last Advertisement, The Ottawa Journal, 17 April 1953Business suffered through the lean years of the Depression and World War II. By the late 1940s, the company was dowdy and old fashioned. In May 1950, Ormie A. Awrey, who had been vice-president and general manager of the firm for the previous eleven years acquired control of the business from the children of the late Charles Bryson and Frederick Graham, buying 85 per cent of the company for $1 million. He later bought the remaining shares. Awrey promised to carry on the traditions of the old firm, but the retailer continued to decline. Parts of the old building were rented out to other retailers, including Bata Shoes, Swears and Wells, and Dolcis. In February 1953, he sold the Bryson-Graham block in February 1953 to J. B. and Archie Dover of Dover’s Ltd for only $310,000. After holding a clearance sale of its stock and fittings, Bryson-Graham, now billed as “Ottawa’s Oldest Department Store,” closed for good on 18 April 1953, ending an 83-year presence on Sparks Street.

The Bryson-Graham building today, corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets, July 2017, Nicolle Powell

The Bryson-Graham building today, corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets, July 2017, Nicolle Powell

Today, the Bryson-Graham building at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets still stands. The ground floor is occupied by Nate’s Delicatessen.

Sources:

Elder, Ken, 2009. Bryson, Graham & Co., Ottawa Canada, http://www.eeldersite.com/Bryson-_Graham_-_Co.pdf.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1920. “Bryson-Graham Ltd Celebrates Its Golden Jubilee, 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Silver Anniversary of Store,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Character of Founder Largely Responsible For Store’s Success,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Battery of Comptometers Used in Bryson-Graham’s Stores,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “Hard Work One Secret Of The Success Won By Messrs. Bryson-Graham,” 28 February.

————————-, 1920. “One-Price Policy Was Introduced In Ottawa By Bryson-Graham Co.” 28 February.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1895. “A Five Cents With A History,” 10 September.

————————–, 1935. “The Shops of the Capital, What they Were and Are,” 10 December.

————————–, 1950. “O.A. Awrey Acquires Control of Bryson Graham Ltd,” 5 May.

————————–, 1953. “Dovers Buy Bryson Blok,” 12 February.

————————–, 1953. “$10,000, Bryson-Graham Sale Heads May Property Deals,” 4 July.

Urbsite, 2012, Sparks Street Department Stores: Bryson Graham and Company, http://urbsite.blogspot.ca/2012/10/sparks-department-stores-bryson-graham.html.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The HSO returns–virtually!

Although COVID-19 continues to prevent us from getting together in person, your Society is getting back in action—virtually!

After a successful, virtual, Annual General Meeting held in July, Ben Weiss has organized three fantastic, virtual presentations to kick off our 2020-2021 speakers’ programme. Leading off will be Michael Kent, the curator of the Jacob M. Lowy Collection at Library and Archives Canada. Michael will be speaking to us about Ottawa’s Jewish history on September 16th. Up second on October 14th will be Jo-Anne McCutcheon from the University of Ottawa. Jo-Anne will be examining vintage Ottawa from 1870 to 1920 viewed through today’s digitized lens. Finally, but by no means least, Stephen Jarrett, Project Manager, Archeological Excavation of Parliament Hill 2019, will reveal to us Parliament Hill’s past on November 18th.

The three presentations will be held at 7:00 pm on the dates indicated using the Zoom conferencing system. While we will miss out on the comradery of our in-person get-togethers, one benefit from going virtual is that our members and friends from outside of the Ottawa area will be able to enjoy and participate in the meetings. So, come and enjoy insightful, interesting presentations on Ottawa’s rich heritage and history from the comfort and safety of your own living rooms! All are welcome.

For more details on how to register and watch the presentations, please consult “Upcoming Events.”

Major's Hill: Ottawa's First Park

21 August 1874

One hundred and seventy years ago, Ottawa, was a rude, crude, muddy shanty-town, newly hacked out of the wilderness to be the northern terminus of the Rideau Canal linking Lake Ontario to the Ottawa River. There were few amenities for its roughly ten thousand citizens, many of whom had settled in the area first to build the canal in the late 1820s, and later to exploit the surrounding forests for their valuable lumber for sale to markets in Britain and the United States. But things began to change once Ottawa was selected as the new capital of the Province of Canada in 1857. Lacking the facilities worthy of a capital, work began in 1859 on constructing Canada’s magnificent Gothic-revival parliamentary and governmental buildings on what was then called Barrack Hill, a bluff overlooking the Ottawa River, and is now known as Parliament Hill. Thoughts also turned to beautifying the town, as well as to providing its burgeoning population with satisfactory, outdoor recreational facilities. As early as 1860, a petition was circulated requesting the Provincial Government to convert Major’s Hill, located to the east of Barrack Hill, into a park for Ottawa’s residents. The petition failed. Despite this setback, the hill was unofficially used as a recreational area, hosting weekend concerts by regimental bands. It was also the site for a huge party and bonfire to welcome the birth of the Dominion of Canada on 1 July 1867.

Initially the hill was called Colonel’s Hill, after Col. John By, the supervising engineer responsible for building the Rideau Canal whose residence once stood on the property. (The foundation of the home, which was destroyed by fire in January 1849, is still visible today.) However, after his deputy, Major Daniel Bolton, moved into the home after Col. By was recalled to England in 1832 to answer for cost over-runs in building the canal, the land became known as Major’s Hill. This name stuck. Back in those early years, the hill was thickly forested, and was known for its great flocks of pigeons, most likely the now extinct passenger pigeons. The species migrated in their millions in eastern North America during the nineteenth century, but was sadly exterminated by the early twentieth century through over-hunting and habitat destruction. According to a letter that appeared in the Ottawa Citizen in 1882, sportsmen hunted the pigeons with “every description of flintlock from the Queen Anne to the blunderbuss.”

In 1864, Ottawa’s Mayor Dickenson sounded out the Provincial Government about the city acquiring the land for a public park “for the future Capital of Canada.” (Government—politicians and civil servants alike—was still based in Quebec City awaiting the completion of their new quarters on Parliament Hill.) This petition, like the preceding one, fell on deaf ears. The Provincial Government was not willing to part with Major’s Hill, seeing it as the possible location for the Governor General’s residence. Plans for such a building on that site had been approved in 1859 but ultimately were never used owing to cost over-runs in constructing Canada’s Parliament buildings. Instead, the government chose to rent, and later to buy, Rideau Hall.

In 1873, the Ottawa City Council again approached the now Dominion Government of Prime Minister Alexander Mackenzie about the possibility of acquiring Major’s Hill as the site for a new city hall, or as a public park. The former idea met popular resistance. But this time the idea of a park found traction. On 21 August 1874, the Dominion government accepted a memorial from the City Council under which the city of Ottawa would lease Major’s Hill for the purpose of a public park, agreeing to “protect the trees and shrubberies thereon,” and to “make roads, place seats, plant trees, erect fences” for the duration of the lease. Council also agreed to hire a full-time caretaker for the grounds, and to build and maintain a road, later known as Mackenzie Avenue, between Major’s Hill and the rear line of lots on the western side of Sussex Street (later Drive). The Dominion Government retained its right to tip excavated material from the Parliament grounds into any holes or waste areas on Major’s Hill. As well, the Dominion Government could take back the park at any time should it have need of the land without compensation being paid to the city.

The following year, Ottawa’s City Council set aside $10,000 (a huge sum in those days) for the development of the park under the direction of Robert Surtees, the city engineer, with work beginning in earnest in the summer of 1875 after the city’s plans had received the Dominion Government’s approval. Initial efforts on levelling the Hill actually commenced prior to receiving the official go-ahead. With the economy in recession, City Council authorized Surtees to commence the levelling of Major’s Hill “in order to give employment to our labouring classes, to enable them to prepare for the hard winter, which, to all appearances, is before them.” Subsequently, perimeter fences and gates were erected, and a formal, semi-circular carriage way along with a number of pathways were created inside the park. Low spots were filled in using clay excavated from Parliament Hill, and an artificial pond was created at the northern end of the park. Fountains were installed, and mounted cannon were placed for decoration. On the horticultural side, a variety of trees were planted, including European sycamore, ash, elm, basswood, maple, and tamarack. Flower beds were also laid out.

Major’s Hill Park, May 2015, looking south toward the Château Laurier Hotel.

Major’s Hill Park, May 2015, looking south toward the Château Laurier Hotel.

Major’s Hill Park, sometimes referred to as Dominion Park, became a major attraction. However, it seems vagrancy and vandalism were persistent problems. In 1878, City Council passed a by-law excluding from the Park “all drunken or filthy persons, vagrants and notoriously bad characters.” Other rules including a prohibition against driving or riding any horse at an immoderate rate, playing football, throwing stones, or shooting with bow and arrow or firearm. People were also prohibited from letting animals, including horses, cattle, swine, or goats, to run free or feed in the park. There was also an explicit prohibition against “carrying any dead carcase, ordure, filth, dust, stone, or any offensive matter or substance.” On the positive side, the playing of games and the selling of refreshments were permitted with permission, though the regulations stressed that the latter would not be permitted “on the Sabbath Day on any pretense whatsoever.”

After spending some $35,000 over the ten years, the cost of maintaining the park was deemed too large, leading the City to hand back the land to the Dominion Government in 1885. Fortunately, the Dominion Government conserved the Hill as a park. Since then, it has been maintained by various federal departments or Crown agencies, including the Department of Public Works, the Ottawa Improvement Commission, the Federal District Commission and, today, the National Capital Commission.

Being a valuable piece of real estate located in the heart of the city, stretching originally from Rideau Street in the south to Nepean Point in the north, Major’s Hill Park was coveted by many as a desirable building site. After the aborted attempt by the City of Ottawa to construct a new city hall on Major’s Hill during the 1870s, consideration was given in 1901 to building a national museum there in a style that would “harmonize” with the Parliament buildings a short distance away. Fortunately, this idea was not approved. However, a few years later in 1909, the Dominion Government under Sir Wilfrid Laurier controversially sold the southern portion of the park to the Grand Trunk Railway (GTR) for the then huge sum of $1 million to build a magnificent hotel—the Château Laurier. The hotel and Union Station railway terminal also built by the GTR on the opposite side of Rideau Street were key elements in Prime Minister Laurier’s plan to make Ottawa the “Washington of the North.” The proceeds of the land sale went to the Ottawa Improvement Commission to develop Nepean Point.

In 1888, the park received its first statue, that of a uniformed guardsman wearing a bearskin hat with his head bowed in mourning and his rifle reversed. It was erected to commemorate the deaths of Ottawa-born Privates W.B. Osgood and J. Rogers, members of the Sharpshooter’s Company who were killed at the Battle of Cut Knife Hill three years earlier in the Riel Rebellion in western Canada. This memorial, which was unveiled in the presence of Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald, his Cabinet, as well as Ottawa’s Mayor and other members of city council, was located close to the southern entrance to the park. When that part of the park was sold to the GTR, the statue was relocated to Elgin Street in front of the old city hall that burnt to the ground in 1931. When the National Arts Centre was constructed on that site in the late 1960s, the statue was moved again, this time to outside the Cartier Street Drill Hall where it stands today.

Statue of Colonel By erected in 1971.

Statue of Colonel By erected in 1971.

In 1971, a statue of Colonel By, sponsored by the Historical Society of Ottawa, was erected in the park as a fitting tribute to the man most responsible for the building of the Rideau Canal, and the founding of the city of Ottawa. The statue by the sculptor Joseph-Émile Brunet, which stands on a granite plinth, portrays the man in his Royal Engineer uniform looking over the Rideau Canal towards the Parliament buildings.

Today, Major Hill’s Park remains as integral part of Ottawa life, offering downtown workers and tourists alike a welcome, verdant space in the heart of the city to rest and play. As was the case almost 150 years ago, Major’s Hill continues to be the focus of city events and celebrations, in particular the annual Canada Day festivities.

Sources:

City of Ottawa, 1864. “Council Minutes,” Petition by Mayor M.K. Dickenson address to the Commission of Crown Lands, re: possible acquisition of Major’s Hill for a public park,” 18 June.

——————, 1974. “Memorial presented to His Excellency to take possession of Major’s Hill and covert the Hill into a park for the use of the public,” 21 August.

——————, 1875. “Council Minutes,”16 August.

——————, 1878. “By-Law #439, “To provide for the maintenance and care of Major’s Hill Park,” 8 July. 2015. “Major’s Hill Park,”

National Capital Commission, 2015. “Major’s Hill Park,” ncc-ccn.gc.ca/places/majors-hill-park.

Newton, Michael, 1981. Lower Town Ottawa, Vol. 3, 1854-1900, Manuscript Report #106, Heritage Section, National Capital Commission.

Ryan, Christopher, “Sharpshooters’ Ambulatory Memorial,” The Margins of History, www.historynerd.ca/?p=260.

Sibley, Robert, 2015. “A haunting monument to Col. By,” Ottawa Citizen, www.ottawacitizen.com/pdf/storiesinstone/storiesinstone11.pdf.

The Globe, 1901, “Site For The New Museum? Advantages of Major’s Hill Park,” 26 October.

————-, 1909. “For a Park and Driveway,” 17 June.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1874. “Major’s Hill Park,” 16 February.

Images:

South End of Major’s Hill, circa 1860, looking from the Parliament Hill construction site. Major’s Hill, located, on the far side of the Rideau Canal, has been largely denuded of trees, photo by Samuel McLaughlin, Library and Archives Canada, c-000601.

Major’s Hill Park, May 2015 by Nicolle Powell

Colonel By statue, Historical Society of Ottawa, www.historicalsocietyottawa.ca.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa's Centenary

16 August 1926

In 2026, Ottawa will celebrate its bicentenary, marking two hundred years from when General George Ramsey, 9th Earl of Dalhousie and Governor General of British North America, wrote to Lieutenant-Colonel John By advising By of his purchase of land for the Crown that contained the site of the head locks for the proposed Rideau Canal on the Ottawa river, and the suitability of the locality for the establishment of a village or town to house canal workers. Lord Dalhousie asked Colonel By to survey the land, divide it into 2-4 acre lots and rent them to settlers, with preference to be given to half-pay officers and respectable people. The rough-hewn community, which was subsequently hacked out of a hemlock and cedar forest, was quickly dubbed Bytown. Its name was changed to Ottawa in 1855, and two years later the town was selected as the capital of the Province of Canada by Queen Victoria.

To celebrate the centenary of its founding by Col. By, the City of Ottawa had a week-long, blow-out extravaganza in the summer of 1926. Although the official opening of the celebrations was on Monday, 16 August 1926, the fun actually began two days earlier on the Saturday with a range of sporting events wide enough to please the most die-hard sports fanatic. The Capital Swimming Club staged a centennial regatta in the Rideau Canal opposite the Exhibition Grounds—a daring event given the poor quality of Canal water. Swimmers from across Canada participated with five Dominion championships at stake. At Cartier Square on Elgin Street, four soccer teams competed for the McGiverin Cup with the Ottawa Scottish emerging the victor, beating the Sons of England with a 5-2 score in the finals. Also featured that day were track and field events, cycling, golf, baseball, tennis and a cricket match at the Rideau Hall cricket pitch.

The following day, there was a huge Garrison Church parade involving 3,000 soldiers including local regiments as well as the Queen’s Own Rifles from Toronto and the Royal 22nd Regiment from Quebec City who had been quartered in tents on the grounds of the Normal School on Elgin Street (now the Heritage Building of the Ottawa City Hall). The troops marched from downtown to Lansdowne Park where 15,000 people crowded into the stands for divine services. More than 50,000 people watched the soldiers march through the streets of Ottawa. That evening the band of the “Van Doos” gave a concert that was broadcast from the Château Laurier hotel.

Devlin Furs’ Float, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025130.

Devlin Furs’ Float, Trades & Industry Pageant, August 1926, Samuel J. Jarvis/Library and Archives Canada, PA-025130.

The official opening ceremonies took place on the Monday morning on Parliament Hill in front of cheering thousands and “in the shadow of the nearly completed “‘Victory Tower.’” (The name for the Centre Block didn’t officially become the “Peace Tower” until the following year—the 60th anniversary of Confederation.) After much military pomp and pageantry, Sir Henry Drayton, delivered the opening speech in the absence of the Prime Minister, Arthur Meighan. He welcomed visitors to the Capital in the name of the Dominion of Canada. Mayor John Balharrie also greeted visitors and former Ottawa residents who had come home for the celebrations. To symbolized the granting to them of the “freedom” of the city, he released a coloured balloon that carried aloft a four-foot golden key. Messages of congratulations flooded into Ottawa from near and far. Three Governors General—Aberdeen, Connaught and Byng—sent telegrams, as did the Lord Mayor of London, and Jimmy Walker, the controversial and flamboyant Mayor of New York. Civic, provincial and federal politicians from across Canada did likewise.

After the official opening, sporting events occupied the rest of the day. That night, there was a military display and tattoo involving troops from all services in from of 12,000 spectators at Lansdowne Park. The chief feature of the night was the staging of a mock battle scene. As searchlights played over the field, the soldiers re-enacted the crossing of the “Hindenburg” line by Canadian troops in 1918. The mock machine gun action and field bombardment was apparently very realistic. So much so that many veterans experienced flash-backs of their time in the trenches. Also featured that night was a performance of the 1,000 voice Centenary Choir, platoon drills by the Royal 22nd Regiment, and gymnastics displays by cadets.

A highlight of Tuesday, the second day of the Centenary celebrations, was the unveiling of a stone memorial dedicated to Colonel By in a small a park located on the western side of the Rideau Canal just south of Connaught Square opposite Union Station. To the strains of Handel’s Largo, played by the band of the Governor General’s Foot Guard, the memorial, which was covered by a Union Jack, was unveiled at noon. Mayor Balharrie presided. More than 2,000 people witnessed the solemn event. The bronze plaque on the side of the stone, which was intended to be the cornerstone of a much larger memorial, bore the inscription 1826-1926 In Honour of John By, Lieutenant Colonel of the Royal Engineers. In 1826 he founded Bytown, Destined to Become the City of Ottawa, Capital of the Dominion of Canada. This memorial was unveiled in Centenary Year. (A larger memorial was never built. A statue of Colonel By sculpted by Joseph-Émile Brunet was eventually commissioned by the Historical Society of Ottawa and was erected in Major’s Hill Park in 1971.)

At Lansdowne Park, a multi-day western rodeo and stampede commenced with over 200 horses, 100 cattle, and dozens of cowboys from western Canada and the United States. Log rolling competitions took place on the Canal. That evening, an historical pageant was held involving 2,000 actors from service groups, theatre groups, and drama schools. The pageant began with a prologue depicting Confederation with Miss Canada seated on a throne exchanging greetings with Misses Provinces. After pledges of mutual support and loyalty, the provinces curtsied to Canada. This was followed by tableaux representing scenes from Ottawa’s history, including “The Spirit of the Chaudière,” depicting the region before the arrival of Europeans, “The Coming of the White Man,” “Pioneer Settlers,” “The Lumber Industry,” “Bytown and its Early Inhabitants,” “The First Election,” “Naming of the Capital,” “The Fathers of Confederation,” and, a finale where all joined together with the Centenary Choir to sing a closing anthem. The massed 1,000-member Choir accompanied by the G.G.F.G. band also performed a number of popular songs including, O Canada, Land of Hope and Glory, Alouette, Indian Love Song, and, of course, God Save the King.

The pageant got a mixed review. The Ottawa Citizen opined that it provided a “felicitous treatment of the historical episodes chosen for presentation,” but there was “room for improvement.” However, on balance, the pageant was “stimulating and educative.” The dancing was described as “effective.”

After the performance, street dancing was held from 11pm to 2am on O’Connor Street between Albert Street and Laurier to the tunes of two jazz orchestras. With the crush of people, there was little actual dancing though things got a bit better on subsequent nights. With massive crowds downtown, there was some minor trouble. The police arrested a number of young men for setting off firecrackers in the streets. Some had placed “torpedoes” on the street-car tracks that caused “terrific successive explosions” as the trams went over them. Police also acted to curb dangerous driving on the crowded city thoroughfares. Reportedly, louts also molested young women. Generally speaking, however, the street partying was carried out in good humour. A dozen youths organized an impromptu game of leap frog on Sparks Street between Bank and Elgin Streets.