James Powell

Operation Fish

2 July 1940

When Sidney Perkins left his house on Euclid Avenue in Ottawa South to go to work on the morning of 2 July 1940, he had no notion that he was about to become part of one of the most secretive and daring operations of the Second World War. An operation that, had it failed, would have meant Britain’s almost certain defeat. Perkins worked for the Foreign Exchange Control Board which had been set up by the Bank of Canada at the outset of the war the previous year to husband Canada’s foreign currency resources. Shortly before noon, Perkins was summoned to the office of David Mansur, the Assistant Chairman of the Board and told that he was to make immediate arrangements to fly to Halifax and meet an important shipment. With the only flight to Halifax leaving in thirty minutes via Montreal, Perkins had no time even to pick up his toothbrush, and had to borrow $100 from two colleagues. After touching down in Montreal, Perkins received an urgent call from Bank headquarters, telling him that plans had changed. Bank staff in Halifax had met the shipment, and that he should wait in Montreal for Mansur who was joining him by car. Mansur arrived in time for the two men to meet a mystery train from Halifax. At Bonaventure Station, a team of five tired Bank of England men led by Alexander Craig disembarked. Craig apologized to Perkins and Mansour for their unexpected visit and said they had brought a “load of fish.”

Roughly two weeks earlier, Craig and his colleagues had received a similar summons from Governor Montagu Norman of the Bank of England who enquired if they were willing to embark on a top secret mission. Agreeing, the men were informed that their task was to shepherd the wealth of Britain to safety in Canada. The mission, code name “Operation Fish,” was a bold, but desperate, gamble by the British Government to protect the gold stored at the Bank of England as well as British-owned, marketable, foreign securities from a threatened Nazi invasion, ensuring that the country had the financial resources to prosecute the war from across the Atlantic, if necessary.

Invasion was a very real possibility that mid-June 1940. German armed forces were on the Channel coast, after having brushed aside the British Expeditionary Force in Europe and crushed the French Army. Although more than 300,000 British and French troops had just been heroically and miraculously evacuated from Dunkirk, they had abandoned enough armaments to equip an army of ten divisions. The British Army was virtually powerless to stop an invasion. Britain’s European Allies were also faltering. Netherland and Belgium had already fallen to the Nazis, while France was on the point of capitulation, the German army having entered Paris on 14 June. To make matters worse, Italy had just entered the war on Germany’s side.

It was not an easy decision to send all of Britain’s foreign assets to Canada. The only way to transport the tons of gold and securities was by ship across the U-boat infested, North Atlantic where 100 Allied and neutral merchant ships had been sunk in May 1940 alone. History was also not reassuring. During World War I, the SS Laurentic, carrying 43 tons of gold from Liverpool to Halifax, had been sunk in 1917 by a German U-boat off of Ireland. The loss of even one treasure ship would have major negative consequences. To buy weapons and other war materiel that it sorely needed from neutral United States, Britain has to pay in gold or U.S. dollars; no credit was permitted under the strict Neutrality Act in effect in the United States at that time.

When storm clouds started to gather in 1938, the Bank of England decided to increase its gold reserves held at the Bank of Canada in Ottawa. In May 1939, fifty tons of gold bars, then worth £14 million (roughly US$2 billion at 2014 prices), was brought over on HMS Southampton and HMS Glasgow. The two cruisers had escorted King George VI and his wife, Queen Elizabeth, across the Atlantic on their Royal Tour of Canada and the United States. A few months later after the outbreak of hostilities, a convoy of five ships, led by HMS Emerald captained by Augustus Agar, VC, DSO, each carrying £2 million in bullion, safely made its way to Canada. The Emerald made another “bullion run” in November 1939, as did other ships over the course of the next several months without incident.

With the Emerald and others having successfully tested the waters, and the war situation in Europe turning grave, Prime Minister Winston Churchill gave the green light to “Operation Fish.” With speed of an essence, limits on the amount that could be sent on individual ships were discarded. The battleship HMS Revenge, accompanied by two converted liners, together shipped £60 million in gold to Halifax in early June. But the real “show” had yet to get underway. On 24 June, the Emerald, now under the command of Captain Francis Flynn, was sent to Halifax, packed to the gunnels with £30 million in gold bullion and £200 million in negotiable securities. The gold was stored in ammunition lockers, while boxes of securities were stashed in every conceivable nook and cranny of the ship, including covering the floor of the Captain’s day cabin on which Alexander Craig, the leader of the Bank of England team, had to make his bed. The Emerald crossed the Atlantic in a full gale. So bad were the weather conditions that its two accompanying destroyers were forced to return to Britain while the Emerald raced at full speed for Halifax. It arrived battered but safe on the morning of 1 July. It was met by the Halifax Agent of the Bank of Canada, a CN train, and a large armed guard. During the ship’s unloading, the perimeter of the dock was tightly sealed to prevent anyone getting a peek at its cargo. That night, the heavily-guarded train, stuffed with gold and securities, set off for Montreal where it was met by Sidney Perkins and David Mansur late the next day.

In Montreal, the train was split in two, with the portion carrying the gold headed for Union Station in Ottawa to be meet by Bank of Canada personnel and armed guards for the short journey to the Bank’s headquarters on Wellington Street. The portion carrying the negotiable securities was unloaded at a secluded siding. In the wee hours of morning, with the streets closed to traffic, the precious cargo was delivered by truck to the Sun Life Assurance Company in Montreal. The Sun Life building, chosen earlier by Mansur to house the “United Kingdom Security Deposit,” was the only building with a large enough secure space to store the securities. A special, custom-built vault was subsequently built in its basement. To assist the Bank of England officials in checking, filing, and managing the securities, Mansur hired 130 retired bankers, brokers and secretaries and swore them to total secrecy. Although the UKSD remained in operation throughout the war, the 5,000 member staff of the Sun Life never knew what was going, or what was stored in the vault beneath their feet.

The Bank of Canada, Wellington Street, circa 1940, Bank of Canada Archives.A week after Emerald’s arrival, a convoy left Britain also bound for Halifax, under the command of Admiral Sir Ernest Archer. It consisted of the battleship HMS Revenge, the cruiser HMS Bonaventure, and three converted former passenger liners, the Monarch of Bermuda, the SS Sobieski and the SS Batory. On board these ships was a treasure trove of gold and securities, conservatively valued at £450 million, of which £192 million was in gold ($27 billion at 2014 prices). Again, the trip across the North Atlantic was difficult. The Batory developed engine trouble, forcing it for a time to come to a dead stop while repairs were made. In thick fog, it safely diverted to St John’s under the protection of the Bonaventure while the rest of the convoy raced to Halifax to be met by Sydney Perkins and other Bank of Canada officials. On board the Monarch of Bermuda was another precious cargo—refugee families evacuated to Canada for safety.

The Bank of Canada, Wellington Street, circa 1940, Bank of Canada Archives.A week after Emerald’s arrival, a convoy left Britain also bound for Halifax, under the command of Admiral Sir Ernest Archer. It consisted of the battleship HMS Revenge, the cruiser HMS Bonaventure, and three converted former passenger liners, the Monarch of Bermuda, the SS Sobieski and the SS Batory. On board these ships was a treasure trove of gold and securities, conservatively valued at £450 million, of which £192 million was in gold ($27 billion at 2014 prices). Again, the trip across the North Atlantic was difficult. The Batory developed engine trouble, forcing it for a time to come to a dead stop while repairs were made. In thick fog, it safely diverted to St John’s under the protection of the Bonaventure while the rest of the convoy raced to Halifax to be met by Sydney Perkins and other Bank of Canada officials. On board the Monarch of Bermuda was another precious cargo—refugee families evacuated to Canada for safety.

Following the routine used previously, the gold and securities were unloaded, weighed and checked before being placed on a special CN train protected by more than 300 police and security guards. This was not an easy task as many of the bullion boxes and bags of gold coins had been damaged in shipment. Perkins later commented that “Seeing those tens of millions in gold piled up gave me a cold chill.” To speed up unloading and minimize the risk of detection, Perkins improvised a metal chute made from scrap metal sheeting to slide crates of gold from the ships’ deck to the quay. Once the train was loaded, and Perkins had officially taken delivery, it set off to deliver the securities to Montreal, and the gold to Ottawa. Again, the shipments were made without anybody outside the operation being the wiser; nothing was reported in the nation’s press. At the Wellington Street head office, bullion boxes came in so fast that Bank staff had difficulty finding places to store them. Crates waiting to be processed piled up in basement corridors and in the incinerator room, used for burning old paper money. Men laboured in twelve-hour shifts to unpack the gold bars and bags of coins and store them in the Bank’s 60 by 100 foot vault. Everything had to be meticulously recorded and accounted for. By the end of it, the Bank of Canada was the home to more gold than anywhere in the world outside of Fort Knox in the United States.

The remainder of Britain’s wealth trickled in over subsequent months, with the redoubtable Emerald making yet another crossing in August 1940. In total, more than £470 million in gold was shipped from the Bank of England in London across the Atlantic to the Bank of Canada in Ottawa. (It value today would be about US$67 billion.) The value of the securities stored in the basement of the Sun Life building in Montreal was then estimated at £1,250 million, their value today, incalculable. Against all the odds, of the dozens of ships used to transport Britain’s wealth to Canada, only one, the merchant ship Niagara carrying £2.5 million in gold from New Zealand, was sunk. Its bullion was subsequently recovered. Despite thousands being involved in the mission, Operation Fish remained a secret until after the war.

Sources:

Bank of England, 194?. Unpublished War History, Chapter V, Gold, Bank of England Archives, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk.

Draper, A., 1979. Operation Fish: The Race to Save Europe’s Wealth 1939-1945, Cassell, London.

McDowall, M., 1997. Due Diligence: A Report on the Bank of Canada’s Handling of Foreign Gold During World War II, Bank of Canada, http://www.bankofcanada.ca/publications/books-and-monographs/due-diligence/.

Naval-History.Net, 1998. Campaign Summaries of World War 2, German U-Boats at War, Part 1 of 6, 1939-40, http://www.naval-history.net/WW2CampaignsUboats.htm.

Stowe, L., 1963. How Britain’s Wealth Went West, http://www.defence.gov.au/sydneyii/SUBM/SUBM.001.0323.pdf.

Images, HMS Emerald, Imperial War Museum.

Image, Bank of Canada, Associated Screen News, Bank of Canada Archives, PC 300-5-61.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Villa St-Louis Tragedy

15 May 1956

Tuesday, the 15th of May 1956 was an unremarkable spring day. The Grey Nuns of the Cross who were staying at Villa St-Louis on the bank of the Ottawa River in Orléans a few miles east of Ottawa went about the timeless routine of convent life. After celebrating Compline, the final church service of the day, the thirty-five mostly elderly residents retired to their spartan cells for the night. There should have been more people staying at the 70-room rest and convalescent home built just two years earlier for $1 million. A group of sixteen student nurses who were about to start a two-week vacation at Villa St-Louis had delayed their arrival to see a play in downtown Ottawa.

The CF-100 “Canuck” Mark V, all-weather fighter/interceptor made by Avro Canada, RCAF photo.

The CF-100 “Canuck” Mark V, all-weather fighter/interceptor made by Avro Canada, RCAF photo.

As the nuns slumbered, two CF-100 “Canuck” Mark V interceptor jet fighters from the 445 Air Squadron based at RCAF Station Uplands were in the dark skies above Ottawa. The fighters had been scrambled to seek out and identify an intruder that had entered their operational airspace. The CF-100s were the most sophisticated flying machines in the RCAF arsenal. They were built by A.V. Roe Canada Ltd, also known as the Avro Canada Company, at the time one of the largest corporations in Canada. The company later became famous for the ill-fated Avro Arrow (CF-105), possibly the most advanced fighter aircraft of the age, cancelled by the Diefenbaker government in 1959.

The fighters were scarcely in the air when the intruder was identified as an RCAF North Star cargo airplane, a four-engine propeller aircraft, travelling from Resolute Bay high in the Arctic to St Hubert, near Montreal. Although the airplane had filed a flight plan, the information had not been received at Uplands. So when an unidentified “ping” appeared on the radar screen, the interceptors were sent up, consistent with military protocol at the height of the Cold War.

With the mystery quickly resolved, one CF-100 returned to base. While accounts vary, the other aircraft, number 18367, piloted by Flying Officer (FO) William Schmidt (age 25) with navigator FO Kenneth Thomas (age 20), apparently asked Uplands for permission to join up with two other Canuck fighters that were heading south at 35,000 feet. The request was denied. So, Schmidt continued west to burn off excess fuel before landing. It was the last flight control heard from the aircraft that vanished from the radar screen over Orléans, falling from 33,000 feet in less than a minute. There had been no hint of trouble.

Interior of the Villa St-Louis Chapel, Orléans, circa 1956, City of Ottawa Archives, MG393-NP-31447-001.At 10:17pm, the CF-100 fighter, fully armed with rockets and machine guns, and with its two crew members aboard, plunged into the chapel of the Villa St-Louis rest home at a speed approaching 700 mph. In an instant, the three-storey, brick building was shattered by a thunderous explosion that sent debris and flames hundreds of feet into the air. Eyewitnesses said the jet had plummeted to ground in an almost vertical dive, the airplane spinning in tight circles, its wing lights flashing in the dark.

Interior of the Villa St-Louis Chapel, Orléans, circa 1956, City of Ottawa Archives, MG393-NP-31447-001.At 10:17pm, the CF-100 fighter, fully armed with rockets and machine guns, and with its two crew members aboard, plunged into the chapel of the Villa St-Louis rest home at a speed approaching 700 mph. In an instant, the three-storey, brick building was shattered by a thunderous explosion that sent debris and flames hundreds of feet into the air. Eyewitnesses said the jet had plummeted to ground in an almost vertical dive, the airplane spinning in tight circles, its wing lights flashing in the dark.

The blast could be heard fifteen miles away. A red glow in the sky was seen in distant Richmond and Manotick. A Trans-Canada Airway (TCA) pilot flying from Montreal to Toronto witnessed an orange ball of fire that lit up the whole sky for seconds. The Villa’s neighbours in the nearby residential area known as Hiawatha Park were thrown from their beds by the force of the blast that also shattered twenty-four windows in St Joseph’s School a mile and a half away. The explosion and ensuing fire, stoked by gallons of aviation fuel and tons of coal stored in the convent’s basement, totally destroyed Villa St-Louis. Within five minutes, the roof of the building collapsed. Two hours later, there was virtually nothing left save a forty-foot chimney and steel girders twisted in the white heat of the blaze.

The speed and intensity of the fire left little time for survivors from the crash to escape. Sister Marie des Martyrs recounted that she had gone to bed at about 9.30pm but had trouble falling asleep. Shortly afterwards, she heard the sound of a low flying airplane—not an unusual sound given that Rockcliffe air force base was but a short distance away. Suddenly, the building was shaken by a terrific explosion that sounded like a thunderclap, followed by splintering wood and breaking glass. There was fire everywhere. Putting on her slippers and robe, she joined other nuns making their way to the fire escape. There was no panic. She descended to the bottom of the fire escape but flames had already reached the lower floor, partially blocking her exit. However, she managed to jump clear and landed uninjured. She believed that she was the last to get out alive.

On being awakened by the explosion, neighbours of Villa St-Louis in Hiawatha Park courageously ran across farmers’ fields to the stricken rest home to help. Many were regular attendees at Mass in the convent’s chapel and knew the resident nuns by name. Rhéal (Ray) Rainville, whose home was less than a mile from the Villa, helped a number of sisters escape from the burning convent. He broke the fall of one elderly resident who leapt from the third floor. He also witnessed the death of Father Richard Ward, the chaplain of the Grey Nuns, who had been blown 150 feet from the Villa by the force of the blast. The priest died in the arms of Joseph Potvin, another neighbour. Lorne Barber, who managed to enter the building, tried to force his way into bedrooms but flames turned him back. He could hear the screams of nuns pounding on the walls for help. Meanwhile, others tried to enter the burning building through its ground floor doors.

Rescued nuns, many burnt or with broken bones, huddled together in the nightclothes on the lawn outside of the burning building. The distraught sisters were taken in neighbours’ cars or by ambulance to the hospital or to their mother-house in downtown Ottawa. The first survivors arrived at about midnight. Many of the injured were sent to the Ottawa General Hospital where they were cared for by the student nurses who were to have begun their holiday that evening at the destroyed home.

Three fire departments, Orléans, Gloucester and the Rockcliffe Air Station, responded to the blaze. But there was little that they could do. RCAF personnel set up road blocks in a vain attempt to stop thousands of spectators from approaching the area. People simply climbed over fences and walked through ploughed fields to get a good look. Cars were parked alongside roads for miles before police began turning vehicles away. People stayed until the early hours of the morning before returning home when the blaze was finally extinguished, aided by a light rain. Many were back at first light.

The next day, the grim task of recovering and identifying the bodies began. Of the thirty-five residents of Villa St-Louis, there were thirteen deaths, eleven Grey Nuns, a lay-woman cook, and Father Ward. Also dying in the crash and explosion were the two young flying officers. Many others were injured by the fire or suffered broken bones. As well as looking for human remains, RCAF specialists combed through the debris to recover the unexploded rockets that the CF-100 carried. Within hours, all but one had been safely found. Souvenir hunters were warned that the missing rocket was dangerous in the wrong hands.

The improbability of the disaster shook Ottawa and neighbouring communities. How could an airplane on a routine interception mission fall out of the sky and strike an isolated convent? Even a slight deviation in the airplane’s flight path would have spared the Villa. Why was such pain and suffering inflicted on a religious order devoted to the care of the sick and injured? What was God thinking? There were no answers to these questions.

Despite subsequent inquiries, the cause of the fatal crash was never ascertained. The two flying officers never sent a distress signal, nor did they use their ejector seats that were standard equipment on CF-100 airplanes. The most likely explanation for the crash was a malfunction in their oxygen system that caused the two men to lose consciousness. This would explain the radio silence in the seconds prior to the crash. The accident report also raised two other possibilities. It was conceivable that the pilot had tried to descend through a gap in the cloud cover and experienced a “tuck under” at supersonic speeds. A “tuck under” can occur when the nose of an airplane continues to rotate downward (i.e. tuck under) at an increasing speed during a high-speed dive. This phenomenon has been known to be fatal if the pilot cannot control the descent owing to high stick forces. Alternatively, Schmidt might have lost control of his aircraft in heavy turbulence caused by the wash of the two other CF-100 fighters that were in the area.

The funeral for Father Ward, who in addition to being the chaplain to the Grey Nuns was also assistant Roman Catholic chaplain to the Fleet, was held the Friday after the disaster at St Patrick’s Church. Archbishop Roy of Quebec, the Bishop Ordinary of the Canadian Armed Forces, officiated. Along with the Grey Nuns, representatives of every congregation of nuns in Ottawa attended. He was buried in Toronto. The following day, a joint funeral service was held for the eleven nuns at Notre Dame Basilica. Thousands of Ottawa citizens lined Sussex Street to witness the funeral cortege—eleven coffins covered by simple grey cloths followed by seven hundred mourning Grey Nuns. Archbishop J.M. Lemieux officiated at the funeral Mass. The deceased were buried in Notre Dame Cemetery.

The following week a memorial service was held for FO William Schmidt and FO Kenneth Thomas, the two flying officers who died in the crash, as well as for a third airman, Flight Lieutenant Al Marshall, who had been killed in the crash of another CF-100 Mark V at a U.S. Armed Forces airshow at Sault Ste. Marie, Michigan on the weekend after the Villa St-Louis tragedy.

Memorial Cross at the site of the Villa St-Louis disaster, August 2017 by Nicolle Powell.

Memorial Cross at the site of the Villa St-Louis disaster, August 2017 by Nicolle Powell.

Today, not far from Residence St-Louis, a francophone seniors’ home that replaced the ill-fated Villa St-Louis, a twenty-foot cross embellished with a jet fighter pointing downwards, marks the spot of the tragedy. At its base are fifteen stones, one for each victim, taken from the convent’s rubble. Plaques list the names of the nuns, the priest, the lay cook, and the two flying officers who lost their lives.

In 2016, sixty years after the disaster, sixty veterans and RCAF members, along with friends and family of those who perished, gathered at the site to remember the lives that were lost that dreadful night in 1956. A bagpiper played the Piper’s Lament.

Sources:

Baillie-David, Alexandra, 2016. “RCAF marks 60th anniversary of Canuck 18367 crash,” Royal Canadian Air Force, 15 May, http://www.rcaf-arc.forces.gc.ca/en/news-template-standard.page?doc=rcaf-marks-60th-anniversary-of-canuck-18367-crash/iophk1cm.

CBC News, 2016. Archives of the 1956 plane crash at the Villa St-Louis, http://www.cbc.ca/beta/news/canada/ottawa/archives-of-the-1956-plane-crash-at-the-villa-st-louis-1.3581477.

Disasters of the Century, 20? CF 100 Convent Crash, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7O89MgA0HDY.

Egan, Kelly, 2015. “Ceremony to mark deadly 1956 jet crash that killed 11 nuns in Orléans,” The Ottawa Citizen, 15 May.

King, Andrew, 2016. “When hell fell from the sky: Fighter jet slammed into convent 60 years ago,” Ottawa Rewind, https://ottawarewind.com/2016/05/14/when-hell-fell-from-the-sky/.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1956. “Crashing Jet Kills 15,” 16 May.

————————-, 1956. “Will Conduct Mass Funeral For Eleven Nuns on Saturday,” 17 May.

————————-, 1956. “Thousands In Streets To Witness Funeral Of 11 Nuns Burned In Fire,” 22 May.

Ottawa, City of, 2017, Disasters, Jet Crash at Villa St. Louis, http://ottawa.ca/en/residents/arts-heritage-and-culture/city-ottawa-archives/exhibitions/witness-change-visions-5.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1956. “Jet Explodes Convent. Struck at 10.15 pm,” 16 May.

————————–, 1956. “Thousands Clog Roads Near Fire,” 16 May.

————————–, 1956. “Villa Suddenly Enveloped By Great Cloud of Flames,” 16 May.

————————–, 1956. “Orleans Scene Of Jet Inferno,” 16 May.

————————-, 1956. “Helped Nuns To Safety And Saw Priest Die On Grass,” 16 May.

————————-, 1956. “I Was the Last Out of the Building,” 16 May.

————————-, 1956. “Two Jet Chasing Unknown Aircraft,” 16 May.

————————-, 1956. “TCA Pilot 10 Miles Away Saw ‘Orange Ball of Fire,’” 16 May.

————————-, 1956. “Hunt Unexploded Rocket Warhead,” 18 May.

————————-, 1956. “Memorial Service Held For Air Victims,” 23 May.

Schmidt, Louis V. 1998. Introduction to Aircraft Flight Dynamics, AIAA Education Series, Reston, Virginia.

Sherwin, Fred, 2006. “Ceremony marks 50th anniversary of Villa St-Louis disaster, Orléans Online, http://www.orleansonline.ca/pages/N2006051501.htm.

Skaarup, Harold A. 2009. “1 Canadian Air Group, Canadian Forces Europe,” Military History Books, http://silverhawkauthor.com/1-canadian-air-group-canadian-forces-europe_367.html.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

University of Ottawa’s HSO Initiative – Great Success!

One early April afternoon, Karen Lynn Ouellette and myself had the honour of attending the last class of Dr. Sarah Templier’s Canadian Digital History course at the University of Ottawa. This was a big day for Dr. Templier’s students who in groups of two or three presented their digital history projects. All the projects were related to the Historical Society of Ottawa. Besides enjoying the wonderful presentations, our job was to help Dr. Templier and PhD candidate, Celeste Dagiovanni, to judge the students’ work, and to select the top three projects. Celeste is the student coordinator of the Venture Initiative Program working with Fahd Alhattab who is in charge of the program as the entrepreneur in residence at the Faculties of Arts, and of Social Sciences.

Sarah Templier, University of Ottawa.The idea of partnering with the HSO was the brainchild of Professor Templier. Before the start of the semester, she had contacted Karen Lynn with the idea of involving her fourth-year digital history students with the Society in some fashion. A number of ideas were floated, including going through the Society’s archives held by the City of Ottawa to document and digitize key documents. However, with the City Archives closed owing to Covid, an alternate project was selected under which student teams would develop websites that contributed to the HSO’s mission and online presence in a meaningful way.

Sarah Templier, University of Ottawa.The idea of partnering with the HSO was the brainchild of Professor Templier. Before the start of the semester, she had contacted Karen Lynn with the idea of involving her fourth-year digital history students with the Society in some fashion. A number of ideas were floated, including going through the Society’s archives held by the City of Ottawa to document and digitize key documents. However, with the City Archives closed owing to Covid, an alternate project was selected under which student teams would develop websites that contributed to the HSO’s mission and online presence in a meaningful way.

In teams of two or three students, five website projects were presented—Epidemics in Ottawa by Jessica Barton and Victoria Pope, Ottawa and the Fur Trade by Danny Bengert and Jordan Johnstone, The Rideau Canal by Charles Wickens, Breanna Campbell and Jameson Holdip, The Murder of Thomas D’Arcy McGee and the Fenian Brotherhood by Jack Lapalme and Thomas Wagner, and The Galloping Gourmet by Rowan Moore and Brenna Roblin. The projects were judged on the basis of how the project contributed to the Society’s on-line presence and mission, the team’s research and ability to reach the target audience, their innovative use of visuals and digital tools that would enhance a reader’s experience, and the ability of each team to effectively “pitch” their project in the allotted time and answer questions.

All five presentations were excellent, making the choice of the top three very challenging. After more than thirty minutes, judges agreed that the top three presentations in order of preference were The Galloping Gourmet, The Rideau Canal, and Ottawa and the Fur Trade. Rowan and Brenna’s winning entry on the television show filmed in Ottawa from 1968 to 1971, styled their presentation in the form of a TV Guide. Their presentation featured recipes, a map of the locations Graham Kerr, a.k.a. the galloping gourmet, visited to inspire his recipes, an interview with a participant who viewed the filming of an episode at the Merivale Road studio, fashion in the 1960s, as well as a section on Graham Kerr’s life after the series ended. Their lively and fun presentation helped to bring to life the late 1960s as well as a little-known part of Ottawa’s television history. It is sure to delight Ottawa history buffs.

In second place, Charles Wickens, Breanna Campbell and Jameson Holdip’s presentation on The Rideau Canal had several innovative features. It was bilingual and acknowledged that the Canal cuts through Indigenous territory. The “then and now” feature was well done. In addition to the usual history of the Canal, the website featured sections on the financing of the canal and what the life of a labourer would have been like. The team noted the importance of the HSO highlighting the significance of the Canal for Ottawa’s upcoming bicentennial.

The third-placed presentation on Ottawa and the Fur Trade by Danny Bengert and Jordan Johnstone provided a useful reminder that life existed along the Ottawa River before the establishment of Bytown by European settlers. It filled a big gap in the HSO’s coverage of Ottawa’s history and heritage, highlighting the contribution of the area’s original Indigenous inhabitants to the fur trade in an engaging and informative fashion.

While the final two presentations on Ottawa pandemics from the early 1800s to the present by Jessica Barton and Victoria Pope, and on the assassination of Thomas D’Arcy McGee by Jack Lapalme and Thomas Wagner did not make the top three, they too treated their subjects well and provided useful insights. We wish we could have provided prizes to all the presenters.

After the students complete their projects, the HSO intends to link the Society’s website to the five student websites so that all those interested in Ottawa history and heritage can benefit from them. As thanks for their hard work on behalf of the Society, each student was given a copy of Controversy, Compromise and Celebration: The History of Canada’s National Flag by Glenn Wright, as well as a one-year membership in the Historical Society of Ottawa. The University also gave cash prizes to the top three projects.

We hope all those who participated in this digital history project learnt a lot about Ottawa’s rich history and had fun in the process. The Society would like to thank Dr. Templier for an excellent initiative and looks forward to future collaboration in the years to come.

James Powell, April 2022.

A Free, Public Library

30 April 1906

While libraries have existed since the emergence of writing in Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt more than four thousand years ago, free, public libraries are a recent phenomenon, dating back only to the nineteenth century. Previously, libraries were the preserve of the Church, kings and wealthy private citizens—the small minority who were literate and had the resources to afford books. Mass education was viewed by elites with suspicion. It might lead people to question their station in life. In a largely agrarian society, knowing how to plough fields, grow crops, and raise livestock were deemed far more important skills for the common person than reading and writing.

Ideas became to shift during the industrial revolution. Social reformers started to advocate in favour of educating workers in order to advance science and reduce superstition. Increasingly, an educated workforce was seen as an economic blessing rather than a social curse. With thousands of men and women pouring into the cities seeking employment in those “dark satanic mills,” the Church and temperance supporters hoped that edifying lectures and libraries would reduce crime, and keep people out of bars and brothels during their (limited) time off. Starting from the early nineteenth century, mechanics’ institutes and literary and philosophical societies, often sponsored by wealthy industrialists, began popping up in the major cities of Britain. These institutions provided lectures on scientific subjects to their members, typically industrial workers and clerks, who could join for a small fee. They also operated libraries and reading rooms for the benefit of their members. In Britain, the Museums Act of 1845 allowed boroughs to raise funds to support museums and libraries for the edification of the general public.

Similar developments took place in Bytown, later Ottawa, albeit with a lag. Calls for a library to be established in Bytown started as early as 1837. Four years later, a small, circulating library opened for subscribers out of the offices of Alexander Gray, a jeweller and bookseller. Unfortunately, it apparently failed after only one year. In 1847, the Bytown Mechanics’ Institute was founded by the town’s leading citizens. In addition to uplifting educational lectures, the Institute provided a library for its members. Drawing principally upon the English-speaking community, the Institute was unable to attract sufficient members, and quickly became inactive. It was, however, revived in 1853 as the Bytown Mechanics’ Institute and Athenaeum (BMIA). Area Francophones established their own cultural institution, l’Institut canadien français d’Ottawa in 1852 that still exists today.

The new BMIA, which received an annual grant from the provincial government, did better than its antecedent. It too provided lectures, classes, a reading room and a small circulating library for its members initially out of the basement of the Congregational Church located near Sappers’ Bridge. By 1856, BMIA had a library of roughly 1,000 volumes, mostly academic works though there were a few novels as well. It also subscribed to British, French and American newspapers, journals and periodicals. In 1869, the BMIA merged with the Ottawa Natural History Society to form the Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society (OLSS). While the new organization continued to offer classes, held lectures, and maintained a growing library, its membership was drawn largely from the ranks of civil servants and industrialists rather than mill workers and labourers. Although a fine Parliamentary Library also existed in Ottawa, its use was also largely confined to the town’s elite rather than the working poor. A small lending library was also maintained by Battle Brothers at the corner of Rideau and Sussex Streets. In 1876, the store, which sold cards of various descriptions, advertised its books could be loaned at two cents per day, along with a deposit.

In 1882, the Ontario Government passed the Free Libraries Act, allowing municipalities to establish public libraries funded out of local taxes with the assent of the ratepayers. A number of cities across the province, including Toronto, took advantage of this new legislation and established public libraries for their citizens. In these cases, the libraries of local mechanics’ institutions were transferred to the new municipally-run libraries. In Ottawa, however, the new legislation had little impact.

During the early 1890s, the Ottawa Council of Women began to lobby for the establishment of a free library in the Capital. In February 1895, the Council, chaired by Lady Aberdeen, the wife of the Governor General, issued the following statement:

“Whereas the Local Council of Women of Ottawa feel that the establishment of a Free Library would be a benefit to the city, resolved: That this Council recommend that the subject be brought prominently before the public through the medium of the press and that a petition to the city council in accordance with the terms of the Free Libraries Act, be prepared for circulation by the Women’s Council.”

The Perley mansion at 415 Wellington St was offered to the City as a home for a public library in 1896. Topley Studio Fonds/Library & Archives Canada, PA-027381.

The Perley mansion at 415 Wellington St was offered to the City as a home for a public library in 1896. Topley Studio Fonds/Library & Archives Canada, PA-027381.

In March 1895, the Council of Women submitted its petition to the city with 280 signatures (almost triple the number required by law). The city then prepared a draft by-law establishing a free library to be voted on by Ottawa ratepayers at the upcoming municipal elections. Ratepayers consisted of men over 21 years of age who owned property in excess of $400. Single women and widows who met the property requirement could also vote. The Council of Women then launched an advertising campaign in support of a free library. With the support of Philip Ross, the editor of The Evening Journal, the Council of Woman published the “Woman’s Edition” of the newspaper in April 1895, with all profits of the edition going to a fund for the free library. In this edition, all the articles, stories and letters were written and edited by women. Front and centre were articles in support of a free library. The movement got a further boost when the heirs of William Perley, a lumber baron, offered the Perley mansion on Wellington Street as home for the new library.

However, the efforts of the women came up short. In the vote held in January 1896, the city’s eight wards all decisively turned down the idea of a public library, with the popular vote 1,958 for and 3,429 against. It seemed that cost of running a library, estimated at about $10,000 per year, was too steep for ratepayers. Instead of becoming a library, the Perley mansion became “The Perley Home for Incurables” until the land was expropriated by the Dominion government in 1912. (In the long run, the location did become a library; the site is now the home of Library and Archives Canada.)

The Council of Women did not give up, and continued to press the issue at city council. But councilmen, while supporting the idea of a free library, collectively continued to reject the idea as being too costly. In 1899, a draft by-law was defeated on second reading on a vote of 13-11. By the early 1900s, with over 400 public libraries in Ontario, Ottawa was looking decidedly backward.

Andrew Carnegie, 1835-1919, Theodore C. Moreau, Library of Congress.Salvation came from the United States. In 1901, Otto Klotz, past president of the OLSS and husband of Marie Klotz who was a leading light in the Ottawa Council of Women’s fight for a public library, wrote Andrew Carnegie, the prominent, Scottish-born, American philanthropist for funds to build a free, public library in Ottawa. The day after Klotz sent his letter, Ottawa mayor W. D. Morris also petitioned Carnegie for funds. By this point, Carnegie had funded hundreds of libraries throughout the United States, Canada, and Britain. Within weeks of receiving the letters, Carnegie pledged $100,000 to pay for an Ottawa Public Library, if Ottawa found a site and if it would agree to spend not less than $7,500 per year in upkeep.

Andrew Carnegie, 1835-1919, Theodore C. Moreau, Library of Congress.Salvation came from the United States. In 1901, Otto Klotz, past president of the OLSS and husband of Marie Klotz who was a leading light in the Ottawa Council of Women’s fight for a public library, wrote Andrew Carnegie, the prominent, Scottish-born, American philanthropist for funds to build a free, public library in Ottawa. The day after Klotz sent his letter, Ottawa mayor W. D. Morris also petitioned Carnegie for funds. By this point, Carnegie had funded hundreds of libraries throughout the United States, Canada, and Britain. Within weeks of receiving the letters, Carnegie pledged $100,000 to pay for an Ottawa Public Library, if Ottawa found a site and if it would agree to spend not less than $7,500 per year in upkeep.

It took several years, however, to bring this about. First, the city hoped that the Dominion government would supply land for the library. When that didn’t happen, city council purchased a site at the corner of Laurier Avenue (then called Maria Street) and Metcalfe Street. Second, it took time to select the design by architect E. L. Horwood out of eleven plans submitted. Third, the project was almost derailed following publication of Carnegie’s views that the United States should annex Canada. But work proceeded. In 1905, council approved $15,000 for the purchase of books, of which $3,500 was spent on French books. Lawrence Burpee, former clerk at the Department of Justice, was selected as Librarian. In turn, Burpee hired an assistant librarian, a cataloguer, three assistants for the circulation desk, and a caretaker. To help expedite the huge task of cataloguing books, Burpee purchased ready-made index cards at a penny a card from the U.S. Library of Congress.

Opening day was Monday, 30 April 1906. Carnegie himself was there for the big event. It was the great industrialist and philanthropist’s first visit to Canada. He came the day before via Toronto, where he had given a speech at the Canadian Club. He was met at the train station by Sir Sandford Fleming and the U.S. Consul General who conveyed him to Government House where he stayed on his short trip to Ottawa. The evening before the official opening, Carnegie was the guest of honour at a formal dinner at the Russell House Hotel. With the prime minister, Sir Wilfrid Laurier, at his side, Carnegie spoke extemporaneously about the union of English-speaking countries, especially the United States and Canada—his favourite hobby horse. Calling himself as a “race imperialist,” he dubbed Canada “the Scotland of America,” and disingenuously envisaged Canada annexing her southern neighbour, just as Scotland had “annexed” England, and “afterwards boss it for its own good, as Scotland did also.” [James VI of Scotland became James I of England at the death of Queen Elizabeth I in 1603.] He also praised Laurier for maintaining Canada’s fiscal independence [from Britain] and for not being swept into the vortex of militarism [a dig at the British who were engaged in an arms’ race with Germany]. Despite Carnegie’s annexationist and racial views, Laurier replied graciously saying that he too was a “race imperialist,” and opined that the separation of England from her American colonies had been a “crime,” and hoped for re-union. He added that had he “not been born of French parentage, there was nothing he would have rather been than a Scot.”

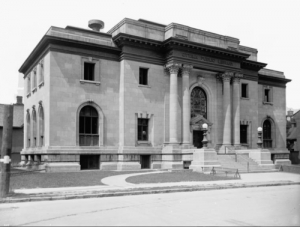

For the official opening the next afternoon, the classical, four-storey library building was clad in Union Jacks, the Stars and Stripes and colourful bunting. Constructed at a cost of slightly less than $100,000, the building was made of Indiana sandstone. The central main entrance was bracketed by four Corinthian columns, two on either side. Above the entrance was a large stained glass window that featured famous authors—William Shakespeare, Lord Byron, Charles Dickens, Thomas Moore, Walter Scott, Lord Tennyson, and the Canadian Confederation poet Archibald Lampman. Overhead, on the lintel of the building, was inscribed the words “Ottawa Public Library” in raised letters. For the official opening, these words were hidden by bunting to avoid embarrassment as the official name of the building was “The Carnegie Library,” a name used by the Ottawa Public Library into the 1950s.

Interior of The Carnegie Library looking towards the main entrance, William James Topley/Library and Archives Canada, PA-009086.The building’s interior walls were clad in Italian marble with beautiful red oak wooden flooring and wainscoting. In front of the entrance hung a portrait of Carnegie painted by Miss V. Fréchette, the daughter of Achille Fréchette the translator of the House of Commons, and Annie Howells Fréchette who edited the “Woman’s Edition” of The Evening Journal in 1895. The basement held classrooms, a newspaper room, a furnace room and the caretaker’s quarters. The ground floor was devoted to reading rooms to the right and left of the large lobby, the librarian’s offices, the stack room as well as the circulation desks. A marble and bronze staircase led upstairs to boardrooms, a reference department, a lecture room for 125 persons, staff offices, and a cloakroom.

Interior of The Carnegie Library looking towards the main entrance, William James Topley/Library and Archives Canada, PA-009086.The building’s interior walls were clad in Italian marble with beautiful red oak wooden flooring and wainscoting. In front of the entrance hung a portrait of Carnegie painted by Miss V. Fréchette, the daughter of Achille Fréchette the translator of the House of Commons, and Annie Howells Fréchette who edited the “Woman’s Edition” of The Evening Journal in 1895. The basement held classrooms, a newspaper room, a furnace room and the caretaker’s quarters. The ground floor was devoted to reading rooms to the right and left of the large lobby, the librarian’s offices, the stack room as well as the circulation desks. A marble and bronze staircase led upstairs to boardrooms, a reference department, a lecture room for 125 persons, staff offices, and a cloakroom.

After the customary welcoming speeches, Carnegie thanked the city and praised it for constructing such a fine building. He then reprised his speech on “race imperialism.” On a tour of the facilities, Carnegie was “waylaid” by a delegation of the St Andrew’s Society who gave the philanthropist an honorary membership to the Sons of Scotland of Canada. After the ceremonies, Carnegie left by train for Montreal, where he was granted an honorary degree at McGill University, and gave yet another speech on race imperialism before returning to New York.

The Carnegie Library was a great success. By the end of 1907, almost 20,000 library cards had been handed out, with an annual circulation of 129,000 books. So successful was it that the old Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society closed for good, its members flocking to the free services provided by the city. Before long, strong demand for the Library led to the establishment of branch operations. In 1916, Carnegie donated an additional $15,000 to build a western branch on Rosemount Avenue. It opened in 1919. This donation was the last Carnegie gave to Canada. He died in 1919 at the age of 83.

Columns salvaged from The Carnegie Library, Rockcliffe Rockeries, 2016, photo by Nicolle Melanson-Powell.

Columns salvaged from The Carnegie Library, Rockcliffe Rockeries, 2016, photo by Nicolle Melanson-Powell.

By the 1960s, the downtown Carnegie library was showing signs of age. Serious cracks had opened up in its walls and ceilings under the weight of the books it contained. In a time when little thought was given to heritage considerations, the beautiful, classic structure was demolished in 1971, a year after the gracious Capitol Theatre also succumbed to the wrecking ball. It was replaced by the current, Brutalist style, concrete building that was completed in 1974. The only thing retained from the old building was the stained glass window. The Library’s Corinthian columns were also saved and were reused as a “folly” in the Rockcliffe Rockeries.

Today, things have gone full circle. Plans have been made to replace the current central library at 140 Metcalfe Street. Also, the aging Rosemount Branch, built a century ago using a Carnegie donation, became too small for current needs; it has been been renovated to increase the public floor space.

Sources:

Bytown Gazette & Ottawa Advertiser (The), 1841, “Circulating Library,” 9 December.

Carnegie Library (The), 1908. 3rd Report, Ottawa: The Ottawa Printing Co. (Limited).

Evening Journal (The), 1895, “Women In Council,” 4 February.

—————————, 1895. “Woman’s Edition,” 13 April.

—————————, 1895, “Free Library Law,”19 December.

—————————, 1896. “Just the Place,” 4 January.

—————————, 1896. “All Jumped On,” 7 January.

—————————, 1899. Free Library By-Law Killed, 5 December.

—————————, 1901. “Free Public Library for City of Ottawa, Carnegie to donate $100,000,” 11 March.

—————————, 1906. “The Program In Ottawa,” 28 April.

—————————, 1906. “The Carnegie Library,” 30 April.

—————————, 1906. “Carnegie Library Formally Opened,” 30 April.

—————————, 1906. “Reception of Library King,” 30 April.

—————————, 1906. “Ceremonies at the Opening,” 1 May.

—————————, 1967. “Old Library to Come Down,” 21 November.

—————————, 1969. “Funds, Weather, Moon Shot Blames for Library Woes,” 12 September.

————————–, 1970. “Library Cracks Up,” 8 August.

—————————, 1971. “Old Building Wrecked by Cohen’s, 24 September.

—————————, 1974. “Salute to the New Central Ottawa Public Library,” 8 May.

Gaizauskas, Barbara, 1990. Feed The Flame: A Natural History of The Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society, Carleton University, M.A. Thesis, https://curve.carleton.ca/b81c434b-04c8-4886-9c97-cfc1a560ff51.

Ottawa Citizen, 1876. “Valentines!”, 2 February.

Jenkins, Phil, 2002. The Library Book: An Overdue History of the Ottawa Public Library, 1906-2001, Ottawa: Ottawa Public Library.

Rush, Anita, 1981. The Establishment of Ottawa’s Public Library, Carleton University.

Urbsite, 2012. Unforgotten Ottawa, The Carnegie Library, http://urbsite.blogspot.ca/2012/09/unforgotten-ottawa-carnegie-library.html?q=Carnegie+library.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The West Block Fire

11 February 1897

When people think of a fire on Parliament Hill, their thoughts likely go to the huge conflagration that destroyed the Centre Block in February 1916. To this day, the cause of that blaze remains unknown; a Royal Commission that investigated it did not come to a conclusion. Some people were convinced, and many still are, that it was an act of war-time German sabotage. Others believed that it was caused by careless smoking in the reading room.

Incredibly, however, the Centre Block fire wasn’t the first major blaze on Parliament Hill. Nineteen years earlier, the West Block, then being used as offices for the federal civil service, was almost consumed by fire.

At approximately 4:15 pm on Thursday, 11 February 1897, when most civil servants had already left for the day, a fire was detected in a small tower room used for storage close to an elevator in the attic storey. An elevator operator tried to extinguish it using a hand-held Babcock fire extinguisher. At the same time, three other men pulled out a fire hose that was installed in the corridor, but when they turned it on the stream of water barely extended three feet owing to low water pressure. Another Babcock extinguisher was brought into play, again without much impact. By this time, the fire was well established in the floor and wall.

At 4:35pm, an alarm was sent in the Central Station of the Ottawa Fire Department located off of Elgin Street. Within minutes, the horse-drawn hose reels arrived and were hooked up to hydrants. Meanwhile, the fire burst through the West Block’s wooden roof about 40 feet south of the Mackenzie Tower. An extension ladder was run up against the western wall of the building where a fireman tried to send a stream of water through an attic window. Unfortunately, only a meager stream came out of the big hose. The city’s low water pressure, made worse by several hoses running from the same Wellington Street water main, was responsible. Flames began to shoot out of a skylight located above the elevator shaft as the fire worked its way southward down the corridor.

In desperation, Fire Chief Young called out the steam-driven fire engines which used coal to heat a boiler to provide water pressure. The Union was stationed at the corner of O’Connor and Wellington Streets, while the Conqueror hooked up to the hydrant located on Parliament Hill at the nearest corner of the West Block. Both engines experienced what a journalist called “exasperating delays” to get water onto the fire. It took the Union almost thirty minutes to get its hose, which extended through the main entrance and up the stairs to the attic, into action owing to valve problems and other malfunctions. Meanwhile, the Conqueror, after failing to get sufficient water from hydrants on the Hill, possibly due to ice, had to be moved to a hydrant at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets. A third fire engine from the E.B. Eddy Company was also brought in to help but to no effect as firemen discovered that its hoses were of a different calibre from that used by the city and couldn’t be coupled to city mains.

Through the evening, fire roared through the upper attic story of the building, fuelled by tinder-dry timbers, a warren of wooden panelled offices and piles of paper—government documents, briefing notes, and memoranda. Flames tore through the roof to the south-west of the Mackenzie Tower and then moved eastward reaching the middle of the Wellington Street side of the building, feeding on flammable materials found in a photographic studio and later in the draughting room of the Marine and Fisheries Department.

By 9:00pm, the whole top storey of the western wing of the building was gone. Shortly afterwards, the top storey of the eastern wing was ablaze. Two hours later, the northern and eastern wings were roofless.

Thousands of spectators, including the Governor General, Lord Aberdeen, and his wife, the Countess of Aberdeen, watched in horror despite the bitter cold; the temperature that evening had dropped to -18 degrees Celsius. It was quite a spectacle. The West Block’s turrets and chimneys were highlighted by the flames with the Mackenzie Tower rearing above the chaos.

While firemen battled the blaze, an army of civil servants and Dominion police worked frantically to empty offices of their documents and other valuables. Even if not immediately threatened with fire, offices on the lower floors were inundated by the water being hosed onto the attic level above. Sleighs of all sorts were pressed into service to evacuate things to the safety of the Langevin Block on the other side of Wellington Street. In the Department of Public Works alone, the Minister and his officials managed to save several tons of books and papers. In the Customs Department, rubber sheets requisitioned from Militia stores were used to protect precious books and papers from water damage.

At 11:00pm, at the height of the fire, Ottawa’s mayor called Montreal for emergency back-up. A detachment of fifteen men from the Montreal Fire Department, equipped with a fire engine and two hose reels answered the call. They immediately set off for Ottawa by train, arriving at 3:00am the next morning. But by this time, the worst was over. The fire had been largely subdued, leaving only glowing embers and smoke.

The next day, Ottawa residents could see for themselves the extent of the damage. Virtually the entire building had lost its top attic floor. The only part of the West Block that was spared was the new wing north of the Mackenzie Tower. This wing, being of more modern construction than the rest of the building, had a metal roof.

The fire continued to smolder despite the deluge of water that had been sprayed onto the building. One fire engine, the Conqueror, was kept pumping water onto the West Block through Friday. However, by 3:00pm, it had to cease operations, having exhausted its stock of hard Welsh coal used to fire its boiler. A switch to ordinary bituminous coal proved unsuccessful in maintaining sufficient pressure to drive the water the long distance from the hydrant at Sparks and O’Connor Streets to the top of the West Block on Wellington Street. The fire revived. An alarm was sounded bringing Chief Young, who had just returned to the station for supper, back on the scene along with another hose reel and two ladder trucks. It wasn’t until 8:00pm that the West Block fire was finally subdued by Ottawa firemen after almost 30 hours of continuous gruelling work in sub-zero temperatures.

The clean-up afterwards was also demanding. Owing to the cold temperatures, hoses were buried under as much as a foot of ice. Even if uncovered, the hoses were frozen stiff, requiring them to be thawed out before being moved. The concrete floor immediately under the attic level was also buried deep in debris.

Even before the fire was out, Cabinet met to discuss rebuilding and to find temporary quarters for affected departments. Only the offices of two departments, Inland Revenue and Railways and Canals remained usable. Space was found in the Nagle building opposite the main entrance to Parliament on Wellington Street for Public Works, Trade and Commerce, Customs and the Public Works departments. The Marine and Fisheries Department moved to offices in the Slater Building on Sparks Street. With more than a foot of water sloshing about in the basement of the West Block where the Dominion Archives were kept, it was imperative to move irreplaceable documents to safety in the Langevin Block. A unit of the Governor General’s Foot Guards stood guard while the papers were transferred.

Amazingly, there were few injuries in the disaster. A fireman suffered a seriously cut finger when a glass skylight fell on him. Another man was hit on the head by a piece of slate thrown from the top of the building during the clean-up; his injury, while painful, was not serious. There were some close calls, however. Four firemen who were fighting the fire in the attic felt the wooden floor beneath them begin to give way. They rushed to a ladder at the window. The first three men made it to safety but the fourth, Harry Walters from the Central Fire Station, had just reached the window when the floor disappeared from under him. He was saved from by William Thompson who managed to grab him.

The official report of the disaster didn’t reach a conclusion about the cause of the fire, though newspaper reports speculated on the possibility of a carelessly discarded cigar or cigarette. Later, a consensus opinion blamed the fire on a “heating apparatus.”

The report did conclude that a doorway cut into a fire wall to permit movement from one office to another helped to spread the blaze. As well, valuable time in fighting the fire was lost owing to firemen being unfamiliar with the layout of office rooms and being unwilling to accept direction from departmental officials. Overall, the report found that officials and workmen had exerted themselves “to the utmost” to prevent the fire from spreading and to save valuable papers and documents. “Nothing which could be done was left undone.”

The cost of the blaze was approximately $200,000. This amount did not, however, include the loss of valuable papers and documents. As the West Block was not insured, the government had to bear the entire cost of reconstruction. The Premier, Wilfrid Laurier, immediately requested a “Governor General’s warrant” to raise $25,000 to cover the initial costs associated with the fire, including the rental of new office accommodations for displaced government offices. The warrant was approved General Alexander Montgomery Moore, Commander of Canada’s Militia, who was acting as the Administrator of Canada on behalf of Lord Aberdeen.

Work on re-building commenced quickly. As a stop gap, a temporary roof, 29,000 square feet in size, was erected at a cost of $4,500. This was later replaced by a fire-proof roof covered with copper. Work also began on the clean-up, the re-building of new offices and the re-furbishing of those offices that managed to survive the blaze but were water damaged. Labourers were paid $1.00 to $1.25 per day. Carpenters and painters received $2.00 per day.

Call for tenders for repairs to West Block, Ottawa Journal, 9 August, 1897.Rebuilding became highly political. The Conservative opposition accused the government of featherbedding and hiring only Hull workers in order to curry favour with Hull voters ahead a forthcoming federal by-election in Wright Country which encompassed Hull. The Liberal candidate, Mr. Louis Napoléon Champagne, was unapologetic saying Hull wasn’t the only city that had obtained patronage as other places got their share of federal business. He added that the Liberals were prepared to do it again “to those who are really friends of Mr. Laurier.” Champagne won the contest. The day after the by-election, 50 of the 313 workers on the West Block were dismissed, with further dismissals expected in order to reduce the size of the work force to what was appropriate.

Call for tenders for repairs to West Block, Ottawa Journal, 9 August, 1897.Rebuilding became highly political. The Conservative opposition accused the government of featherbedding and hiring only Hull workers in order to curry favour with Hull voters ahead a forthcoming federal by-election in Wright Country which encompassed Hull. The Liberal candidate, Mr. Louis Napoléon Champagne, was unapologetic saying Hull wasn’t the only city that had obtained patronage as other places got their share of federal business. He added that the Liberals were prepared to do it again “to those who are really friends of Mr. Laurier.” Champagne won the contest. The day after the by-election, 50 of the 313 workers on the West Block were dismissed, with further dismissals expected in order to reduce the size of the work force to what was appropriate.

Repairs were sufficiently advanced within a year to permit public servants to re-occupy their offices. But work on the West Block was not completed until 1899, more than two years after the fire.

The West Block fire led to considerable reflection on the size of the Ottawa Fire Department and its equipment, and the extent of the fire hazard posed by public buildings, particularly those on Parliament Hill. The Citizen opined that Ottawa was “comparatively helpless in the presence of a major conflagration.” The “noble government structures,” which cost $5-6 million to build, were the “crowing beauty of the Capital of the Dominion.” Yet, the buildings, constructed using wooden beams and partitions and filled with irreplaceable records, papers and documents, were fire traps. The newspaper contended that should fire break out in either the Central Block or the East Block, “the result would be equally bad” as what had just occurred.

It added that the House of Commons was particularly at risk since the Centre Block was built on a higher elevation that the West or East Blocks which meant that water pressure would be even more of a problem. The Library of Parliament was “the most serious case of anxiety,” as it held more than $1 million in books, and contained no dividing walls. Given these risks, the newspaper was appalled that smoking was permitted and argued that smoking should be banned in all public buildings.

These were prophetic words. Virtually nineteen years to the day later, on 3 February 1916, the Centre Block was destroyed by fire. The precious Library of Parliament was the only part of the building saved, owing to the quick thinking of a librarian who had the presence of mind to close an iron fire door that separated the structure from the main part of the building.

Over the decades that followed, the West Block was much altered. In 1911, a new wing was built linking the east and west wings to form an enclosed quadrangle. During the mid-1950s, the West Block suffered from extensive renovations which were unsympathetic to the original design. However, this was better than the alternative. In 1956, the St. Laurent government almost manage to achieve which the 1897 fire had failed to do—the complete destruction of the beautiful and historic Gothic-revival building. The Federal District Commission, the fore-runner of the National Capital Commission, wanted to replace it with a modern office tower. But after a nation-wide protest, wiser heads prevailed and the building was saved. However, the neighbouring Supreme Court building was not so lucky. It was destroyed to make way for a parking lot.

Today, the enclosed quadrangle in the middle of the West Block, now covered by a glass ceiling, is the temporary home of the House of Commons while the Centre Block undergoes much needed restoration and renovation.

Sources:

Ottawa Daily Citizen, 1897. “The Western Block in a Blaze,” 12 February.

————————-, 1897. “The Second Alarm,” 13 February.

————————-, 1897. “A Present Danger,” 13 February.

————————-, 1897. “After The Fire,” 15 February.

————————-, 1897. “Their Usefulness Done,” 25 March.

————————-, 1897. “West Block Blaze,” 24 June.

————————-, 1898. “West Block Fire,” 24 March.

Ottawa Evening Journal, 1897. “The Talk of Today,” 13 February.

——————————, 1897. “The Official Report,” 17 February.

—————————–, 1897. “The Wright Campaign,” 17 March.

—————————–, 1897. “An Insult To Hull,” 18 March.

—————————–, 1897. “One Million Dollars,” 27 March.

—————————–, 1899. “West Block Repairs,” 9 August.

Privy Council Office, 1897, “Special Warrant $56,000 [sic] [$25,000], Fire, Western Departmental Buildings – Minister of Public Works,” 17 February, Library and Archives Canada.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Poulins: Ottawa's Store of Satisfaction

2 February 1929

L. N. Poulin, Ltd, known to all as simply Poulin’s, ranked among the finest retail stores in Ottawa during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. It was known for excellent service, fair dealing, innovative advertising methods, and low prices. During its early years it billed itself as “Ottawa’s most progressive store.” Later, it styled itself as “Ottawa’s store of satisfaction.”

For forty years, the store stood at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets in the heart of the capital’s business district. Then, out of the blue, L. N. Poulin, its founder, announced in late 1928 that he was retiring and that the store would close. Within two months, the grand retailer was gone, shutting its doors for the last time on 2 February 1929 after a month-long “Retiring from Business Sale.” Other than his retirement—L. N. Poulin was 70 years of age at the time—no other reason was cited for the closure. Poulin rented his building on a long-term lease to Schulte-United Corporation of 485 Fifth Avenue New York, a thrusting, new firm that was opening “five and dime” stores across North America.

Poulin’s was started in 1889 by Louis Napoleon Poulin and his wife Mary Poulin (née McEvoy). Mme Poulin is given little credit for starting the firm in contemporaneous accounts (not surprisingly given the times) but her obituary noted that she was a considerable businessperson in her own right. L. N. Poulin was born in 1858 in a log home in Addison, Ontario, near Brockville. At age thirteen, he got a taste of retail selling by doing chores and odd jobs at Messrs. Nichols and Parker in the nearby town of Toledo. At sixteen, he took a train to Ottawa to make his fortune. Apparently, he had a return ticket to Brockville in his pocket should things go wrong. He didn’t need it.

In Ottawa, he found employment with Russell, Gardiner & Legatt, one of the largest merchant firms in the capital. He worked there, and at another firm, Stitt & Company, for eleven years before he and his wife struck out on their own in 1889; the couple had married in 1884. Most accounts of Poulin’s early years place his store in a small frame building at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets, a location that he occupied in bigger and bigger establishments for the next 40 years. However, there are newspaper references to a L.N. Poulin dry goods store at 99 Bank Street through the 1889-90 period. The company ran an advertisement for a “removals sale” in the Ottawa Evening Journal in early April 1890. This suggests that it was about then that the Poulins made the move to their permanent home at the corner of Sparks and O’Connor Streets.

Mr. L. N. Poulin, Ottawa Citizen, 18 June 1923. Poulin, aided by two assistants, rented 600 square feet on the ground floor of the building from John A. Brouse for $50 per month. The budding dry goods firm only had $4,000 worth of stock. One of his first customers was reportedly Lady Macdonald, the wife of Sir John A. Macdonald.

Mr. L. N. Poulin, Ottawa Citizen, 18 June 1923. Poulin, aided by two assistants, rented 600 square feet on the ground floor of the building from John A. Brouse for $50 per month. The budding dry goods firm only had $4,000 worth of stock. One of his first customers was reportedly Lady Macdonald, the wife of Sir John A. Macdonald.

The firm was a success. In 1892, Poulin bought the Brouse property which also housed the Dymond shirt factory and the YMCA. Two years later, he took over two buildings to the west on Spark Street (the Bush-Bonbright store and National Manufacturing Company) and purchased a milk factory at the rear on O’Connor Street. In 1902, Poulin bought more property on Spark Street giving him 132 feet of frontage. In 1906, he expanded further, buying the Mills Hotel from the Misses Piggott to the rear of his property which gave him a uniform depth of almost 100 feet. Two years later he acquired the J.M. Garland property on O’Connor Street with a view to future expansion. In 1915, this became the store’s house furnishings annex.

By 1923, the store had more than 73,000 square feet of floor space, with stock valued at close to $500,000. It employed 245 people. That year, the enterprise expanded for the last time, demolishing the old annex and erecting a four-storey extension which added an additional 18,000 square feet of floor space. This new structure was integrated with the original main building. Looking to the future, it was constructed in a fashion that allowed for six more storeys to be added at a later date.

The store was noted for its innovative approach to advertising. One spectacular example of this occurred during the summer of 1904. Poulin’s announced its “Lucky Money Back Sale.” A date during a six-week period was selected at random by Mayor Ellis and place in a sealed envelope in the vault of the Bank of Ottawa. Neither the Mayor, the bank manager, or Mr. Poulin knew the selected date. All sales on that date would be refunded in full. Poulin advised customers to shop at his store every day of the sale to ensure being a winner. At the end of the sale, the sealed enveloped was open and the lucky date revealed—23 August, 1904. All customers on that date were given three days to return to the store with their sales receipts to “receive “the full amount of your checks in NEW, CRISP MONEY.”

Poulin’s Sale, Ottawa Citizen, 9 July 1924.It was innovations like this, along with every-day good value and courteous service, that made the store an Ottawa landmark. So, imagine the feelings when Poulin announced that he was retiring and the store would close. The Ottawa Citizen described it as the passing of an institution. “It did not seem right nor did it seem natural.” It was not as if the store was unprofitable, or there were no heirs to carry on the family name. Indeed, the Poulins’ four sons, Edmond, Gidias, Fabien and Clement, all worked in the family firm. The closure also meant that almost three hundred employees lost their jobs. At a farewell dinner dance held for his workers a few days after the store’s shut its doors for good, Poulin said that his employees would be able to find new careers if they did their best.

Poulin’s Sale, Ottawa Citizen, 9 July 1924.It was innovations like this, along with every-day good value and courteous service, that made the store an Ottawa landmark. So, imagine the feelings when Poulin announced that he was retiring and the store would close. The Ottawa Citizen described it as the passing of an institution. “It did not seem right nor did it seem natural.” It was not as if the store was unprofitable, or there were no heirs to carry on the family name. Indeed, the Poulins’ four sons, Edmond, Gidias, Fabien and Clement, all worked in the family firm. The closure also meant that almost three hundred employees lost their jobs. At a farewell dinner dance held for his workers a few days after the store’s shut its doors for good, Poulin said that his employees would be able to find new careers if they did their best.

If the rationale for the closure appears somewhat mystifying, Poulin’s timing was impeccable. Less than nine months after the store went out of business, the Great Depression began. The Schulte-United Corporation, which had moved into the former premises of Poulin’s department store, failed two years later, a casualty of the economic catastrophe.

Closing out sale, Ottawa Citizen, 30 January 1929.

Closing out sale, Ottawa Citizen, 30 January 1929.

Another person who had impeccable timing was Walter P. Zeller of Kitchener, Ontario. In 1928, he had sold his small chain of Zeller’s department stores located mostly in southern Ontario to the Schulte-United Corporation which wanted to expand into Canada. When Schulte-United failed three years later, Walter Zeller bought the Canadian wing of the operations. These comprised his original Zeller’s stores and ten other outlets that Schulte-United had established in the interim, including the former Poulin’s department store location on Sparks Street.

Zeller’s became a fixture on Spark Street for more than seventy years. The very profitable chain of bargain stores was bought by the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1978. Growing to roughly 350 stores by the year 2000, the Zeller’s chain began to lose ground to competitors. Profitability declined. In 2011, the U.S. department store chain Target bought the leases of most Zellers stores for $1.825 billion in its ill-fated effort to break into the Canadian retail market. It promised to run them under the Zeller’s brand for a “period of time.” The larger Zeller’s branches were eventually remodelled and converted into Target outlets. Smaller ones, like the elderly store on Spark Street, did not fit the Target style. It closed its doors in 2013. Two years later, Target closed all of its 133 Canadian stores after a disastrous foray into Canada.

The distinctive building once owned by L. N. Poulin was almost demolished in the early 1980s as part of a high-rise development plan. Notwithstanding a demolition permit granted by Ottawa’s City Council, the building was saved at the last minute, in part by a campaign orchestrated by Heritage Ottawa. It was sympathetically renovated by its then owners, the Hudson Bay Company. Consistent with its long heritage as a discount retail store, the edifice that was once Poulin’s Department Store, and later Zeller’s, now houses a Winners outlet.

As for the Poulins, after their retirement, the couple moved to a home at cottage community of Britannia. Louis Napoleon Poulin stayed active in Ottawa’s commercial life as a director of the electric and gas companies. He died at the age of 85 in 1941. His wife, Mary Poulin, died in 1949.

Sources:

Heritage Ottawa, 2017. Poulin’s Dry Good Store| Zellers Department Store, https://heritageottawa.org/50years/poulins-dry-goods-zellers-department-store.

Ottawa Citizen, 1904. “Thousands of Dollars in Cash Refunded to Our Customers,” 11 July.

——————, 1904. “Your Money Back,” 2 September.

——————-, 1923. “Rebuilding of L.N. Poulin, Limited, Store To Add Another Chapter To Fascinating Story of Expansion Of An Ottawa Firm,” 19 June.