Memory Project

The Historical Society of Ottawa Memory Project is an initiative designed to preserve and celebrate the history of our community and its members. This project aims to collect, digitize and preserve the personal stories, photographs and documents of those who call, or have called, Ottawa home. As part of doing so, we are committed to highlighting the diverse experiences of BIPOC, disabled, and LGBTQ+ people who continue to enrich our community.

Through this project, we hope to preserve these stories for future generations and to provide accessible, educational resources for all those interested in learning more about the history of our city. By celebrating our shared history, we're building a stronger, more connected community where everyone's story is valued and remembered.

If you have a story you’d like to share, please reach out to This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Completed memory projects can be found below.

Following World War II, approximately 40,000 Holocaust survivors resettled in Canada. Ottawa became home to many of those Holocaust survivors and hundreds of their descendants.

The Ottawa-based Centre for Holocaust Education and Scholarship invited 11 of those survivors to share their stories.

The Historical Society of Ottawa is honoured to link their testimonials to the HSO Memory Project:

Over the past few years, the Historical Society of Ottawa has been privileged to have had the opportunity to collaborate and work closely with the Cumberland Township Historical Society, whose continuing mission is to discover, share and preserve the important history of the former Cumberland Township, now part of the amalgamated City of Ottawa.

Beginning in 1986, a team of forward-thinking CTHS volunteers set out to record interviews with some of Cumberland Township's older residents at the time, capturing priceless accounts of bygone times.

Now, for the first time, the CTHS is sharing all of these recordings on their website.

HSO is pleased to present the link to these precious recorded interviews: www.cths.ca/voices-from-the-past-voix-du-passe

Ottawa’s Camp Woolsey, Guiding, and the Power of its Community

Sadie CannJulie Côté on Ottawa’s Camp Woolsey, Guiding, and the Power of its Community

Could you introduce yourself and tell us how you’re involved with Girl Guides?

My name’s Julie, but a common thing in Girl Guides, especially at Camp Woolsey, was to use fake names or ‘camp names’. So my camp name is Jaf, and that’s what most of the people involved in Guiding in Ottawa would know me as.

I’ve been a member of Girl Guides for basically my whole life. I started in 1997 when my family was posted in Germany. When my family moved back to Canada, I joined as a Brownie. Girl Guides of Canada has recently changed the branch name to Embers, but originally the branch was named after a type of Scottish Fairy. After Brownies I did Guides, Pathfinders, and Rangers but took a break when I went to university. When I came back to Ottawa I became a Guider, and have been a Guider ever since, going on 10 years now.

The biggest reason I stayed as a kid was because of two really good friends, who I met in Guides. They weren’t going to my school, so that was the only time I saw them. The three of us did the leadership training program at Woolsey together, and my first job was working at camp. It was this friendship that kept bringing me back. When I said earlier I took a break from Guides, that was only half true. While technically I wasn’t a member, I still worked at camp. When I got back to Ottawa, the reason I joined again was because some of my friends had a unit and asked me if I could help out. As a kid, I was never interested in working with other kids, but that changed and now I work for the school board.

When I was 12 or 13 there was a big change in the way Girl Guides was run. It became a lot more centralised. No longer did we have “districts” that handle their own affairs, like the Ottawa District for example. It was actually the Ottawa District that first bought and ran Woolsey right from the very start. There have also been program changes and uniform changes. The organisation is always trying to evolve and keep up with the times.

Could you tell me a bit about the camp itself?

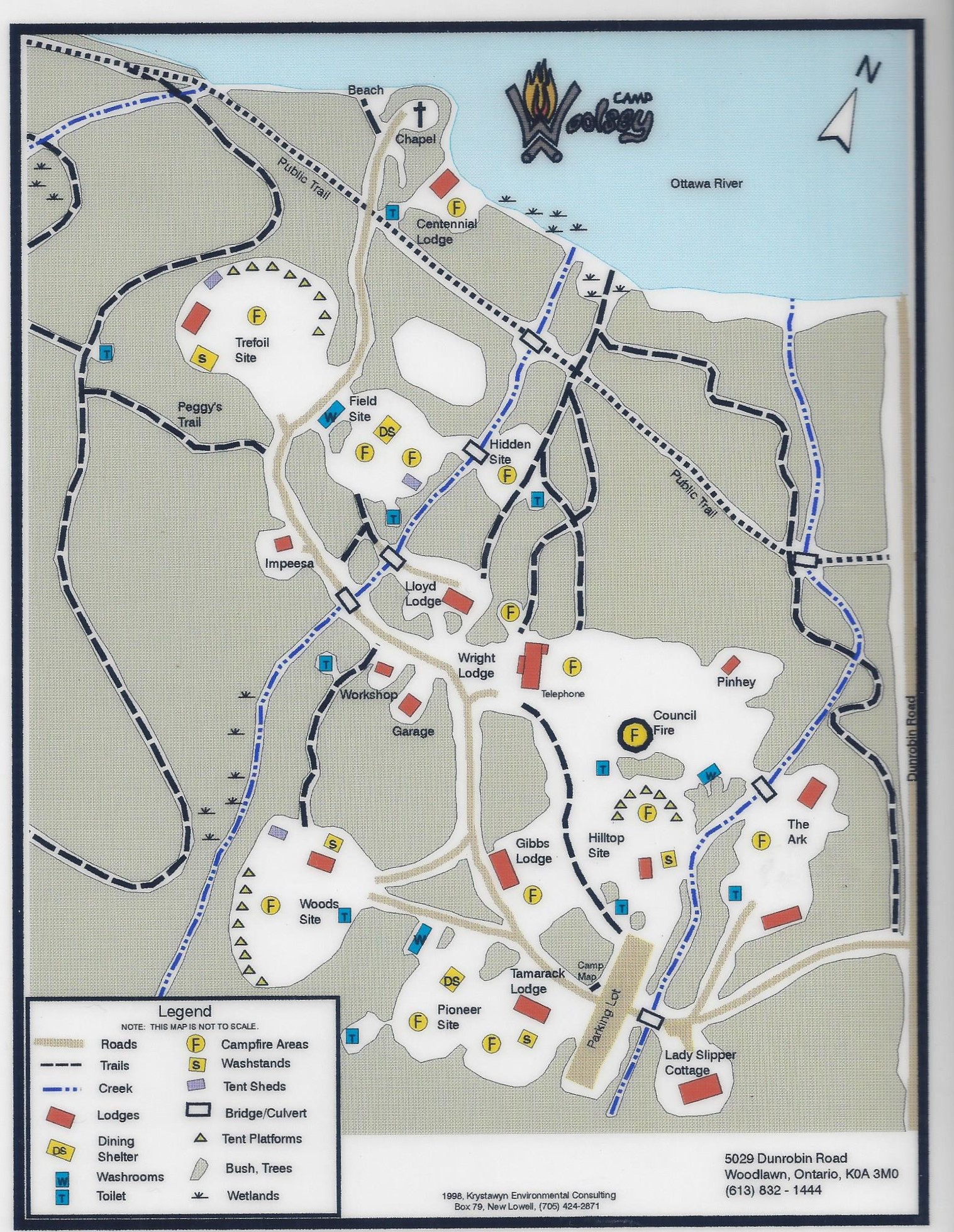

The camp opened in 1937 and ran for 82 years, making it the second oldest Girl Guide camp in Ontario. It was named after Mary Woolsey and her husband Edgar. It was Mary that spearheaded the campaign to raise money for a camp in Ottawa. The property itself is quite old, it was originally a farmer’s field. At the time, there was one farmhouse on the property, which is still standing today. The building is called Pinhey, named after one of the early women, Anna Pinhey, who helped raise money for the camp. It was built in 1824, which makes it 200 years old!

The first building built after the camp was established was Lloyd Hall in 1937. Lloyd Hall named after Wilmont Lloyd. Since Guides was mostly tenting back then, they needed a place to store food and cook. The original building did fall into disrepair, but they’ve since built a new one in its place.

The first time I ever went to Woolsey was 2003. I was really interested in their canoe program, and even did some canoe trips in Algonquin park. In 2007 I did the leadership program and worked at camp from 2008-2017. I had a whole bunch of different jobs during that time. I was a lifeguard at first, and eventually the Day Camp Program Director (2016-17). Those years we ran a day camp and an overnight camp at the same time. My job was overseeing the day camp staff and campers. In 2018 and 2019 I went back to volunteer for a few weeks because I was travelling during the summer, so I wasn’t available to work. Then the camp closed in 2020.

Why did Woolsey close?

I’m not an expert on the behind the scenes part of that, but I can speak to it a little. In 2017, an email was sent around from Girl Guides saying that it was too costly to run the Ontario Girl Guide camps. They said a lot of people weren’t using Girl Guide owned properties. I can’t speak to the rest of Ontario, but in Ottawa, our guides were using Woolsey. However not all the camps ran summer programs and I could see how smaller camps may have been losing money.

Woolsey’s last summer should have been 2020, but the pandemic cancelled the summer season. The camp was then sold in 2021. Throughout this time, we were told there could be ways to save the camps. For example, if the camps could make enough money, or if people had proposals, they’d reconsider. I honestly don’t know how that went. There were a few proposals, but obviously nothing worked. Woolsey’s last major event was a “Thinking Day” event, which happens on February 27 every year. It’s a day we learn about the history of Guiding. We didn’t know the camp was closing at the time, but it was nice to have that final special event.

Camp Woolsey has since become a camp ground called Camp Capital, and I actually got to take one of my units there and wake up in Lloyd Lodge for the first time since 2018.

Woolsey wasn’t the biggest camp in Ontario, but we ran a pretty popular program. Usually we had about 200-250 kids a week, and we ran for eight weeks. One of the things about Woolsey was that you didn’t actually have to be a member of Guiding to go to the camp. So a lot of kids would bring their friends who weren’t in Guides.

Now that Woolsey is closed, each individual unit has a specific place they meet every week. These places could be schools, churches, community centres. We don’t really have a dedicated space in Ottawa anymore. We used to have a Guide Store, but that closed in 2008 or 2009. In terms of my units, my current Spark unit has 20 kids, which is at the limit. My older group, the Trex, is 15 right now, but could be bigger. The older the kids are, the less Guiders you need for the ratio of supervision.

Do you have any fun memories or stories from your time at Woolsey?

When you work with kids, there’ll always be funny memories. Some of my favourite memories from working at the camp in the summer were the traditions we had. I already mentioned camp names, and it became a game for the kids to try and guess what your real name was. Luckily my camp name is kind of vague, and since my real name is Julie, it was really easy to get away with tricking the kids. If I ever needed to initial a form, they both started with J. For some people their camp name might have been their favourite animal, or their favourite character or food. One of my friends actually convinced the kids her real name was Tortillia.

One of the other games we played every week was called counsellor hunt and the idea was the counsellors were all afraid of something, and we’d run away and hide. The kids would have to try to coax us to come back to the main space with them, which was called the Council Fire. Maybe they had to figure out what we were scared of, then draw us back, and then we joined their team. There was a series of little challenges we had to do and the kids could vote on which counsellor they wanted to represent them. So we’d do the silly challenge. One of my favourite parts of it was if you could think of a way to cheat in an entertaining way, you could usually get away with it.

My personal counsellor hunt victory was in a game where we had to stack cups blindfolded. We had to make the biggest tower within a certain amount of time. What we didn’t realize was that there was only one stack of cups available. So I grabbed the stack and hopped away from where everyone else was. What I didn’t know was that I had only left 3 or 4 cups behind. I balanced the cups on my head and sat still while the other three counsellors fought over 4 cups! I won that challenge, and it was my absolute favourite moment of the game.

Another thing I loved about camp was regatta day, where we did a bunch of beach activities. Regatta had this recurring creature called the Swamp Monster, that would show up and try to spook the kids. At the end of Regatta, she would run off the end of our dock and the lifeguards got to chase her. As a kid, I always thought this was really funny, and then I got to participate once I became a lifeguard. I realized quickly it was very difficult to run on our docks because they were floating docks. It was fun to see this happen as a kid, and then participate in it as a counsellor.

Celebrating Camp Woolsey's 80th birthday

Celebrating Camp Woolsey's 80th birthday

Is there anything else you want to share?

My friend Emma Kent and I are currently writing a book about Woolsey. We started the project before we knew the camp was closing, so around 2017. We initially created a Facebook page for people to share memories and that’s how we got the inspiration to turn this story into a book. We’re very very close to finishing, and hoping to have the book out this summer.

The Facebook page is called ‘The History of Camp Woolsey’.

Some historical photos of the camp:

1947 Pinhey

1947 Pinhey

1948 Hilltop Site

1948 Hilltop Site

1948 Lloyd Lodge

1948 Lloyd Lodge

David (Dave) Kent - Beep Ball, Disability, and Sports Memory in Ottawa

In March 2024, the Historical Society of Ottawa sat down with David (Dave) Kent to discuss beep ball, disability and sports memory in Ottawa.

Why don’t we start by telling a bit about yourself and your life?

Dave: Well I was born in Ottawa in the summer of 1951 and did almost all of my schooling, elementary, middle and high school in Ottawa. I went to the University of Ottawa in the early '70s and did an arts degree in Geography. I then went to the University of Manitoba to take a course in data processing, or what they call computer science now. I had normal vision until I was about 8 or 9, when I lost 90% of my sight.

And what was it like attending public school with a visual impairment?

Dave: In the 1960s, it was normal for any kid with any difference to be sent off somewhere, like the Ontario School for the Blind in Brantford or similar schools for deaf children. There were also sunshine classes for the kids in wheelchairs. My parents wanted me to stay in the public school system in Ottawa because they knew I’d have to adjust to this anyways. But there were no organized supports, it often depended on what the teacher thought they could do to help. Sometimes my teacher might copy a test from the blackboard onto paper for me or use the sideboard instead.

The program I took at the University of Manitoba was supported by the CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) and the governments. I think it was called Data Processing for the Blind. The reason I took the course, even though I already had a Bachelor's degree from the University of Ottawa, there weren’t any jobs at the time. So I now worked 35 years in what became information technology, 7 years for the Federal Government and 28 years for the City of Ottawa in their IT team, designing programs and databases. In about 1980, I met my wife. We’ve been together 40 years now and have six kids. We also have a cat named Tintin. So that’s the 5 minute biography.

So can you explain to me what exactly beep ball is and how you became involved? I think I have an idea from my Google searches but I’m not sure.

Dave: So beep ball or beeping baseball has its origins in the US, probably in the early '60s. The culture in the US was that there was really only one sport: baseball. The NFL, NHL, and the NBA were just fledgling organizations. The only real sport was baseball, “America’s game” or “America’s pastime.”

There was a group of former Bell telephone employees called the Bell Pioneers, and they believed every boy in America should be able to play baseball. So they created a baseball the size of a softball with a pin, and inside there’s a device that beeps. When you pull the pin out it starts beeping, and when you put it back in it stops.

In the US, it’s played by someone throwing the ball in the air to a blind batter, hitting it, and then running to a beeping base. That isn’t quite the way we played. We played the more traditional version where the batter would be blindfolded, with six fielders, also blindfolded, but the pitcher and the catcher were sighted. The pitcher would pull the pin to make the ball beep, he or she would say “ball coming” and then roll the ball across the ground. The batter would be kneeling, and sweep their bat across the ground to hit the ball.

The batter would start running towards first base with the assistance of a guide. In the field, when the ball was caught, that ended the play. If the batter made it to the base, they were safe. If they were caught between bases, they were out. Beep ball was also played on grass rather than a baseball surface because quite often, you’re on your hands and knees crawling around and such. In 1992, Maclean-Hunter, a Canadian cable company, actually did a ten minute video for us, so we have that on VHS.

How I became involved was that my wife's father was actually working for CNIB in 1986. At the time, CNIB was trying to put together a summer activity program for their client base. They had a fellow called Murray Thorpe, and he decided to start a beep ball league for the clients with the idea that it promotes physical and social activity. There was a real concern amongst the blind community about physical activity, and of course, blindness can be socially isolating.

So that’s how I first got involved.

How often did you play?

Dave: We used to play on a weekly basis. At the time, there was actually a beep ball tournament in Belleville, and we ended up winning the first couple of years.

After that first summer, the group of us who met one another through beep ball continued to play for the next few years. In 1990, Ottawa was part of the Twinning Games, which involved an exchange of athletes between Ottawa and The Hague. The people from The Hague came here and we wrote to the City of Ottawa saying we’d be interested in meeting some of their blind athletes. A group came over who played Showdown, a game very much like air hockey. If you saw it and didn’t know what it was, you’d think they were just playing air hockey. So it worked out really well because both cities were worried about finding a group on either side who could accommodate their needs.

In 1991, Ken McColm was walking across the country. He was a blind fellow walking across Canada for diabetes because that’s how he had lost his sight. When he got to Ottawa, I got in touch with the Diabetes Association and we put together a beep ball exhibition game against the CJOH NoStars on the main lawn of Parliament Hill. The Diabetes association then asked if we’d be interested in running a tournament next year. This was at a time when Hope Volleyball was really big, so we wanted to create a beep ball tournament. In 1992, we had B.A.T., the Blind Awareness Tournament on Parliament Hill with four teams. In 1993 we had eight teams. In '94 it was 16 teams and we moved to St. Paul’s University. We then got too big for people to run this part-time, so that was the last of the B.A.T. tournaments, but we continued to play after that.

In the city at the time there was a blind sports club called the Capital Eyes, so we used that pun. As the Capital Eyes we were part of the Ottawa disabled sports club, we even had our own shirts!

What other activities did you participate in? Did you engage in politics at all?

Dave: Apart from our normal play, we used it for reverse integration, so we’d take the equipment to schools, guide meetings, and offices to play with sighted folks. This really was reverse integration and it gave those people a chance to see what it would be like to not see or have to rely on other people.

We didn’t do any political lobbying, we were more recreational. But we did have various people come out to see us, like the head of Baseball Canada. We wanted them to know that, hey, we’re out here too and we’re playing too. He had never heard of beep ball, he was fascinated. During one of our tournaments we also commissioned the Dominion Carillon player Gordon Slater to play Take Me Out to the Ball Game on the Peace Tower Carillon.

Throughout your career, have you seen any changes in the way people discuss disability?

Dave: There was certainly a change in attitude between elementary school and high school, and when I got to university. When I went to university, the only thing people cared about was if you could do the work.

When I first entered the workforce there was a reluctance or a concern about hiring an individual who was blind. They were concerned about if you could do the job, so you had to prove you could do it before their concerns were alleviated. I found the people I was working with very supportive. But if you interviewed with people in other organizations, the first thing they’d realize was that this guy has a problem, and did they really want to invite a problem into their workplace. So I suspect I may not have gotten some jobs over my life because of their lack of vision, not my lack of vision.

There were no accommodations when I entered the workforce in 1975, everything was print based, so at one point I did have a manual sent off the CNIB to enlarge it. But really no special accommodations. I’ve now been out of the workforce for 13 or 14 years so I can’t really talk about the present day. Certainly technology has changed a lot. There's a lot of accessibility features built into devices that didn’t exist most of the time I was working.

Listen to Dave explain the origins of beep ball and how it's played in Ottawa.

And, in this linked video, Dave shows us what a beep ball looks and sounds like.

Learn the Beep Ball - Rules of Play.

Further Reading and Resources:

- About the CNIB: https://www.cnib.ca/en?region=on

- About the Bell Pioneers: http://www.telecompioneers.ca/pioneer-links/bellaliant

- Get involved with Ottawa’s Miracle League: https://www.miracleleagueofottawa.com

- About Diabetes Canada: https://guidelines.diabetes.ca/about

-

About Hope Volleyball Ottawa: https://hopehelps.com