Super User

Lord Stanley’s Cup

18 March 1892

Each spring as winter’s snows begin to recede, the thoughts of Canadians turn to the Stanley Cup. One of the oldest sporting trophies in the world, the Cup is the symbol of hockey supremacy in North America. Its provenance is well known; it was purchased and given to the hockey community by Lord Stanley of Preston, Canada’s Governor General, in 1892. What is less well known is that Ottawa featured prominently in the Cup’s story. It was in Ottawa that Stanley let it be known his intention to provide a championship trophy. As well, during his vice-regal tenure in the nation’s capital, the Governor General, an avid hockey fan, and his equally hockey-mad children, did much to make hockey Canada’s national game. The Ottawa Hockey Club also played in the first Stanley Cup championship game.

The sport of ice hockey has a long history. It probably originated in “ball and stick” games played by both Europeans and natives peoples in North America. Shinny, an early form of ice hockey, was played on rivers or ponds in Nova Scotia during the early nineteenth century. Shinny could involve scores of players on each team, using a wooden puck, one-piece hockey sticks and hockey skates. Modern ice hockey dates from early 1875 when Halifax native James Creighton organized an indoor game at the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal. Given the constrained skating surface, teams were limited to nine per side (reduced to seven in 1880). Played with a flat wooden disk using hockey sticks made by Mi’kmaq carvers from Nova Scotia, the game used “Halifax Rules” that included a prohibition on the puck leaving the ice and no shift changes. The match was an overwhelming success for both its participants and its appreciative audience.

In response to growing interest in the sport in central Canada, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC) was formed in 1886 with five teams, four from Montreal (the Victorias, the Crystals, the Montreal Hockey Club, and McGill College) and one from Ottawa, the Ottawa Hockey Club, known as the Ottawas. The Ottawas were established in 1883 and were a frequent participant in hockey games held during the Montreal Winter Carnival during the 1880s.

Lord Stanley of Preston arrived in Canada in 1888 to take up his position as the Dominion’s sixth Governor General. An avid sportsman, he was introduced to the game of ice hockey in February 1889 when he and members of his family, including his eldest son Edward and daughter Isobel, visited the Montreal Winter Carnival. Arriving while a hockey game was in progress—play was temporarily halted on his arrival—the Governor General, his family and friends watched the Montreal Victorias defeat the Montreal Hockey Club.

Lord Stanley was instantly hooked on the game. He quickly built an outdoor rink at Rideau Hall, his Ottawa residence, for the use of his family and staff. He took to the ice himself, though he apparently got into some trouble for skating on the Sabbath. In March 1889, his Rideau Hall rink was the site of what is believed to be the first woman’s hockey match between a Government House team on which Isobel Stanley played, and a Rideau ladies team. Her brothers, Edward, Arthur, Victor and Algernon, were also keen hockey players. They played with various official aides, MPs and senators on a team dubbed the “Rideau Rebels,” but more formally known as the Vice-Regal and Parliamentary Hockey Club. The Rebels played exhibition games throughout eastern Ontario including Kingston and Toronto that helped to popularize the game. The fact that Lord Stanley had placed his vice-regal stamp of approval on the game was another important factor in hockey’s rapid acceptance as Canada’s national winter sport.

In 1890, Lord Stanley’s son, Arthur, along with two team mates from the Rideau Rebels, helped create the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA), composed of thirteen teams from Toronto, Kingston and Ottawa, later joined by a team from Lindsay. Today, the OHA oversees junior hockey in Ontario. During the late nineteenth century, long before there was a National Hockey League and professional players, OHA teams represented the cream of Ontario hockey. The Ottawa Hockey Club team played in both the OHA and the AHAC centred in Montreal.

The Stanley Cup dates from 18 March 1892. That night, a celebratory dinner for members of the Ottawa Hockey Club was held at the Russell House Hotel. The Russell House was Ottawa’s top watering hole at the time, standing at the north-eastern corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets, roughly between today’s National War Memorial and the National Arts Centre. The Ottawas had just finished a championship year, winning the Cosby Cup of the OHA and holding the AHAC championship from January to early March before losing it to the Montreal Hockey Club. The Ottawa Evening Journal noted that the back of the dinner’s menu cards recorded the achievements of the team: nine championship matches won to only a single defeat, during which the team scored 53 goals “against the best teams in Canada,” allowing only 19 goals the other way.

Accounts differ on the number of people at the dinner. The Journal reported that there were between 70 and 80 present, while the Montreal Gazette said that about 200 admirers attended. The latter, larger number probably reflected the addition of the ladies who joined the men after the dinner for “ices.” Mr J.W. McRae, president of the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association, the senior umbrella sporting association to which the Ottawa Hockey Club was affiliated, presided over the soirée, while the band of Governor General’s Foot Guards provided suitable musical entertainment.

At about 10pm, after the loyal toast to Queen Victoria, followed by another toast to the health of the Governor General, Lord Kilcoursie, an aide to Lord Stanley, rose to reply on behalf of the Governor General who had been unable to attend the evening’s event. After thanking the gathering, Kilcoursie read out a letter from Stanley. Dated 18 March 1892, it said:

I have for some time past been thinking that it would be a good thing if there were a challenge cup which should be held from year to year by the champion hockey team in the Dominion. There does not appear to be any such outward and visible sign of a championship at present, and considering the general interest which matches now elicit, and in the importance of having the game played fairly and under rules generally recognized, I am willing to give a cup, which shall be held from year to year by the winning team.

I am not quite certain that the present regulations governing the arrangement of matches give entire satisfaction, and it would be worth considering whether they could not be arranged so that each team would play once at home and once at the place where their opponents hail.

The letter was enthusiastically received by the partisan hockey crowd.

Kilcoursie also revealed that the Governor General had commissioned his former military secretary, Captain Charles Colville of the Grenadier Guards, who had recently returned to Britain, to purchase an appropriate trophy on Stanley’s behalf.

After a series of more toasts, including one to the Ottawa Hockey team as well as others to members of the league, the Press and the Ladies, the dinner broke up at about midnight, though not before many songs were sung. In particular, Lord Kilcoursie entertained the party goers by singing a “ditty” titled The Hockey Men that he had personally composed to honour the members of the Ottawa Hockey Club. The first two verses went:

There is a game called hockey

There is no finer game

For though some call it ‘knockey’

Yet we love it all the same.

This played in His Dominion

Well played both near and far

There’s only one opinion

How ’tis played in Ottawa.

At the end, the crowd gave “a rousing chorus, rendered in stentorian style” according to the Journal, repeating the third verse of the eighteen-verse poem:

Then give three cheers for Russell

The captain of the boys.

However tough the tussle

His position he enjoys.

And then for all the others

Let’s shout as loud we may

O-T-T-A-W-A!

Over in England, Captain Colville purchased Stanley’s Cup from the London silversmiths G.R. Collis of Regent Street for the sum of 10 guineas (ten pounds, ten shillings). As one pound was worth $4.8666 in Canadian money, this was the equivalent to $51.10, a considerable sum in 1892. On one side of the silver bowl with a gilt interior was engraved “Dominion Hockey Challenge Trophy,” while the inscription “From Stanley of Preston” with his family coat of arms was on the other. The Cup arrived in Ottawa the end of April 1893 and was entrusted to two trustees, Sheriff John Sweetland and Philip D. Ross.

The original Stanley Cup. The silver bowl stands 19cm high and has a diameter of 28.5 cm and a circumference of 89 cm

The original Stanley Cup. The silver bowl stands 19cm high and has a diameter of 28.5 cm and a circumference of 89 cm

Library and Archives CanadaThe trustees announced that the Cup would henceforth be called the “Stanley Cup” in honour of its donor and, as specified by Lord Stanley, it would be a “challenge” cup. In other words, the Cup would be open for all. Any team could challenge the holder of the Cup for the championship title though the two trustees had the final say on whether a challenge would be accepted. Other conditions included the requirements that a winning team keep the trophy “in good order,” that each winning team (except for the first winner) would engrave its name on a silver ring fixed to the trophy at its own cost, that the Cup was not the property of any one team, and that in case of doubt over who was rightly the champion team in the Dominion, the trustees’ decision was final.

Unfortunately, the presentation of the first Stanley Cup in May 1893 was mired in controversy. The Montreal Amateur Athletic Association (MAAA) was awarded the trophy by virtue of the 7-1 victory of its affiliated hockey team, the Montreal Hockey Club, over the Ottawa Hockey Club, the OHA champions. The trustees duly engraved Montreal AAA on the Cup, and arranged for Sheriff Sweetland to present the trophy at the Association’s Annual General Meeting. The president of the Montreal Hockey Club, James Stewart, who was also a player on the team, was asked to attend the Annual General Meeting to receive the Cup. However, Stewart refused to accept the trophy until the terms and conditions related to holding the Cup were clarified. Enraged by this decision, and not willing to embarrass the Governor General’s emissary, Stewart accepted the Cup from Sweetland on behalf of the MAAA.

The spat between the MAAA and the Montreal Hockey Club went on for some months. After a number of letters between the two organizations and between Sweetland and Ross, a reconciliation was achieved, and the Stanley Cup was finally transferred to the Montreal Hockey Club in time for the 1894 championship game. Held in late March of that year with the Ottawa Hockey Club, their long-time rivals, the match attracted some five thousand cheering fans to the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal. After Ottawa took a one-goal lead, the Montreal team stormed back with three unanswered goals to win the game 3-1 and the Cup. Later, the neutral words “Montreal 1894” were engraved on the Cup to avoid any hard feelings between the parent Montreal Association and its related Montreal Hockey Club.

Sadly, Lord Stanley, the man behind the Cup, was not there to witness the first challenge match for his trophy. He had returned home the previous summer to take up the duties as the 16th Earl of Derby following the death of his elder brother.

Sources:

Batten, Jack, Hornby Lance, Johnson, George, Milton Steve, 2001. Quest for the Cup, A History of the Stanley Cup Finals 1893-2001, Jack Falla, Genera Editor, Thunder Bay Press: San Diego.

Hockey Hall Of Fame, 2016. Stanley Cup Journal.

Jenish, D’Arcy, 1992. The Stanley Cup: A Hundred Years of Hockey At Its Best, McClelland & Stewart Inc.: Toronto.

McKinley, Michael. 2000. Putting A Roof On Winter, Greystone Books: Vancouver.

Montreal, Gazette (The), 1892. “Lord Stanley Promises To Give A Championship Cup,” 19 March.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1892. “Stars of the Ice.” 19 March.

————————————, 1893. “The Stanley Cup.” 1 May.

Shea, Kevin & Wilson, John J., 2006. Lord Stanley: The Man Behind The Cup, Fenn Publishing Company Ltd: Bolton, Ontario.

Vaughan, Garth, 1999. The Birthplace of Hockey.

Wikipedia, 1891-92, 2014. Ottawa Hockey Club Season.

Images:

Lord Stanley of Preston, 1889. Topley Studio/Library and Archives Canada, PA-027166.

The Stanley Cup, Library and Archives Canada.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Catch

28 November 1976

The afternoon of 28 November, 1976 was chilly and overcast in Toronto, with the temperature hovering about the freezing point. A stiff northwesterly breeze made it seem even colder. But the weather did not deter the more than 53,000 exuberant Canadian football fans that crowded into Exhibition Stadium that afternoon for the 64th Grey Cup Championship between the Saskatchewan Roughriders and the Ottawa Rough Riders. It was a record crowd and a record gate of $1,009,000. Both teams had finished the regular season in first position in their respective divisions. To reach the Grey Cup, Ottawa had bested the Hamilton Tiger-Cats in the eastern divisional final held the previous weekend in a close 17-15 contest, while Saskatchewan had topped the Edmonton Eskimos 23-13 in the west. The western Riders were five-point favourites owing to the strong arm of their veteran, all-star quarterback, Ron Lancaster, and the best defence in the Canadian Football League. Saskatchewan had also beaten Ottawa 29-16 in their only meeting of the regular season. Despite the youthful Ottawa team’s lacklustre play during the second half of the season, it was no pushover. Its coach, George Brancato, had been named the CFL’s coach of the year in 1975, and had put together back-to-back first place finishes for the eastern Riders.

Televised coast-to-coast by both CBC and CTV, this Grey Cup game promised to live up to its pre-game hoopla. But fans could not have known that they were about to be treated to one of the greatest, if not the greatest, championship game in CFL history. It featured the heroics of unlikely players, broke Grey Cup records, and, with the outcome in doubt into the last minute, ended in one of the most thrilling plays seen in Canadian football. Sports fans will always remember it as “The Catch.”

Ottawa was the first to draw blood. With slightly more than five minutes left to play in the opening quarter, Gerry Organ scored a field goal from Saskatchewan’s 30-yard line. With the western Riders retaking control of the ball, Ottawa’s defence held tough, forcing Saskatchewan to punt, setting the stage for Bill Hatanaka, the 22-year rookie kick returner out of York University. Catching the ball booted by Saskatchewan kicker Bob Macoritti, Hatanaka scampered 79 yards for a touchdown, the first punt return touchdown in Grey Cup history. It was also the longest Grey Cup punt return to that time, and only subsequently surpassed twice. It was 10-0 Ottawa at the end of the first quarter.

Late in the second quarter, Ottawa’s fortunes soured when Macoritti finally put the western Riders on the board with a 32-yard field goal. With the Ottawa offence under the direction of sophomore quarterback Tom Clements (“Captain Cool”) unable to sustain a scoring drive, this was quickly followed by a Saskatchewan major when Ron Lancaster found wide receiver Steve Mazurak who ran 15 yards for the touchdown. With Macoritti’s convert, the game was tied at 10. Seconds later, Ted Provost intercepted an errant pass from Tom Clements, intended for Ottawa’s star receiver, Tony Gabriel. This set the stage for another Lancaster touchdown throw, this time to tight end, Bob Richardson. Again Macoritti converted. The score was 17-10 in Saskatchewan’s favour at half time. Despite the score, everything had not gone in Saskatchewan’s way. Running back, Molly McGee, suffered a rib injury late in the quarter after a bruising tackle, crimping Lancaster’s running game.

In the third quarter, the two teams traded field goals. With a stiff wind favouring Saskatchewan, the Ottawa defensive team did great work in holding the western champions to only three points. Late in the quarter, Ottawa fans were brought to their feet by Jerry Organ, who faked a punt and ran 52 yards to bring his team deep into Saskatchewan territory. Organ’s gamble, caught Coach Brancato by surprise. After the game, Organ revealed that the play originated in a half-time dressing-room discussion with linebacker Mark Kosmos about Saskatchewan not rushing punts. Organ said that he “ran like a scared rabbit,” and had planned to kick the ball had he got into difficulty. Unfortunately, his heroics were snuffed out when Saskatchewan linebacker Cleveland Vann intercepted another one of Tom Clements’s passes. Seven points continued to separate the two teams as they entered the final quarter.

With only 7.33 minutes left of the final frame, Gerry Organ kicked a 32-yard field goal to bring Ottawa to within four points of their rivals. On the next series of plays, the Ottawa defensive squad stopped Saskatchewan midfield. With third down and less than a yard to go, the Saskatchewan’s coach, John Payne, decided to punt the ball instead of trying for the first down. It was an uncharacteristic conservative play. It was also a fateful decision with huge consequences.

Macoritti’s punt gave the Ottawa Rough Riders the ball on their 26-yard line with five minutes to go. Tom Clements then went to work, methodically working the sticks down field to bring Ottawa just outside the Saskatchewan 10-yard line. After a short pass to Art Green, Clements attempted to run the ball in himself but was tackled short of the first down, and tantalizingly close to the goal line. It was third down and less than a yard to go. With 1:32 remaining on the clock, and Ottawa needing at least four points, Coach Brancato decided to gamble. But the Saskatchewan’s defensive wall stopped the eastern Riders inches short of the first down. With the western Riders taking possession of the ball, it looked like Saskatchewan had the Grey Cup in the bag.

But they hadn’t counted on the Ottawa defence. Promising Coach Brancato one last chance, the defensive team gave up only six yards, forcing Saskatchewan to punt into the wind from their own 7-yard line. Ottawa’s Hatanaka, returned the ball to the western Riders’ 35-yard line. In two plays, Clements moved the ball down to the 24-yard line, with a pass to Tony Gabriel picking up the first down. With only 31 seconds remaining on the clock, everybody knew that Clements would try to find Gabriel again, his go-to-man the entire season…everybody, that is, except the Saskatchewan Roughriders who failed to double cover the scoring threat. Waving off a play from Coach Brancato, quarterback Tom Clements sought out Tony Gabriel who, first faking a post pattern, had turned instead to the outside. Clements found him in the clear, five yards behind Saskatchewan’s Ted Provost in the end zone. The Ottawa quarterback launched the ball. Gabriel reached above his head and pulled it in. Touchdown! Fans poured onto the field and mobbed Gabriel in the end zone. With Gerry Organ’s convert, the Ottawa Roughriders went ahead 23-20.

Although Saskatchewan had one more opportunity to score, with only 20 seconds left in the game, there was simply not enough time. Ottawa became the 1976 Grey Cup Champions. The perfectly executed 24-yard touchdown pass from Clements to Gabriel went down in CFL lore as simply “The Catch.” Clements was named the game’s most valuable offensive player, while Gabriel was named the most valuable Canadian. Saskatchewan’s Cleveland Vann was the game’s most valuable defensive player. Members of the winning team each received $6,000 bonus, with the losing team members each receiving $3,000. Tom Clements, as the top offensive player of the game, was also given a new car, a timely prize as is old one was the “team’s joke.”

Back home in Ottawa, the place went wild as fans poured onto the streets. Bank Street turned into a parking lot as fans celebrated their Rough Riders’ victory, honking horns and consuming vast quantities of beer as police turned a blind eye to minor infractions. At noon the next day, the team returned home, greeted at the airport by hundreds of fans and a brass band. A civic celebratory dinner was held for the team that night. The event totally eclipsed a black tie dinner hosted by Prime Minister Trudeau on Parliament Hill for Team Canada, winner of the 1976 Canada Cup Hockey Tournament the previous September.

The 1976 Grey Cup was the Ottawa Rough Riders’ ninth and last CFL Championship. Although the team again made it to the finals in 1981, they went down to defeat 26-23 to the Edmonton Eskimos. The Ottawa Rough Riders team collapsed in 1996 owing to falling attendance, poor management, and growing debts. Founded in 1876, the oldest professional sports team in North America was no more. In 2002, a new team, the Ottawa Renegades, briefly played out of Landsdowne Park, but it too folded after only four years. In 2014, another Ottawa team, the Redblacks, wearing the familiar colours of their storied predecessors, took the field.

UPDATE (27 November 2016): Ottawa Redblacks win the Grey Cup! In an exciting contest in Toronto, the underdog Ottawa Redblacks held off a fourth-quarter surge by the Calgary Stampeders to take the Cup 39-33.

Sources:

CBC, 1976. 64th Grey Cup Game.

CFL, 2014. 64th Grey Cup, November 28, 1976.

The Globe and Mail, 2012. “Punt return in ’76 Grey Cup was one for the record books,” 23 November.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1976. “Grey Cup Returns to Ottawa,” 29 November.

———————–, “Football Fervor spoils hockey heroes’ dinner,” 29 November.

———————–, 1976. “Battle was saved in the third quarter,” 29 November.

———————–, 1976. “Organ weighs future,” 29 November.

———————–, 1976. “Clements, Gabriel dynamite,” 29 November.

———————–, 1976. “Inventive gambling pays,” 29 November.

Ottawa Citizen.com, 2006. “Our last Grey Cup ever?,” 26 November.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Contact Us

Questions, queries, suggestions, comments? We'd love to hear from you!

The Historical Society of Ottawa

Box 523, Station "B",

Ottawa, ON

K1P 5P6

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

Follow Us

Marconi Radio Station, CFCF, formerly XWA, Montreal, circa 1922

Marconi Radio Station, CFCF, formerly XWA, Montreal, circa 1922Read the story

Local Museums

Click the map of Ottawa to explore local museums

Bytown Museum

"Located in the heart of downtown Ottawa, the Bytown Museum explores the stories of an evolving city and its residents from its early days as Bytown to present day Ottawa."

Ottawa Museum Network

Twelve Ottawa-area community museums, in-person and online.

Perth & Area Museums

A list of the museums in Perth and surrounding area.

Renfrew County Museums Network

"The Renfrew County Museums Network (RCMN) was formed in 2002 so that all of the county museums in operation at that time could both share technical information and collectively promote their facilities. ... At our museums throughout Renfrew County we celebrate the stories that have shaped the history of Canada."

Videos

On April 28, 2021, Dorothy Phillips, author and longtime HSO member, told us about researching and writing the story of the Duke of Devonshire during his time as Governor General of Canada.

If you missed the HSO presentation by Phil Jenkins (or you just want to watch again) check out his recap and reflections on the history of LeBreton Flats in this video from April 14, 2021.

Ottawa resident and award-winning author Charlotte Gray shared with us the story of the life and death of Sir Harry Oakes on March 31, 2021.

On March 10, 2021, Andrew King, Ottawa artist, cartoonist, columnist, and author of the Ottawa Rewind books and blog, shared some of his discoveries of long-hidden secrets from Ottawa's fascinating past.

The Day My Students Met Mandela: Nelson Mandela's Remarkable 1998 Visit to Ottawa

Wendy Alexis shared stories and memories with us on February 10, 2021, about the day that Nelson Mandela visited the Canadian Tribute to Human Rights monument in Ottawa.

Camp Woolsey: 80 Years of Life-Long Friendships & Memories

Share some memories of the Girl Guide Camp Woolsey in this HSO presentation by Emma Kent on January 13, 2021.

Rare film footage of Churchill's 1941 visit to Ottawa provided courtesy of Michael Evans.

Read about Churchill's visit in this recounting of the event by James Powell: Some Chicken, Some Neck - 29 December 1941.

Kettle Island: A Bridge to Ottawa's Past

Randy Boswell, Journalism Professor, Carleton University, explored the surprising history of Kettle Island in a virtual presentation to the Historical Society of Ottawa on December 2, 2020.

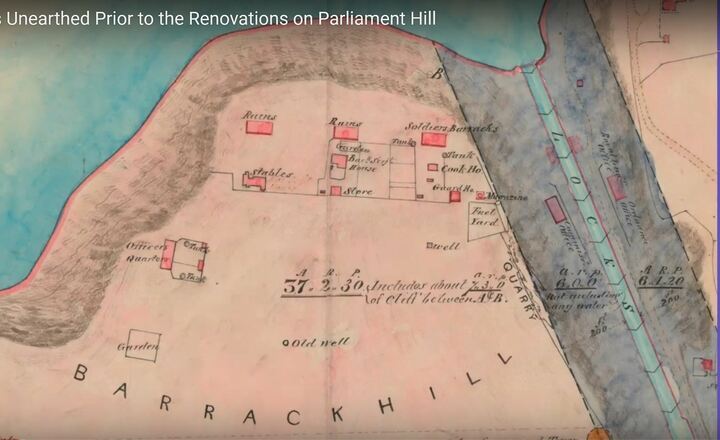

Uncovering Canada's Past: Digging up Parliament Hill

On November 18, 2020, Stephen Garrett, Project Manager of the archeological excavation of Parliament Hill in 2019, shared stories and discoveries from his work in a virtual presentation to the Historical Society of Ottawa.

Using Digital Tools to Explore and Share Ottawa's Past

At the HSO virtual presentation on October 14, 2020, Jo-Anne McCutcheon of the University of Ottawa shared with us how technology and digitization techniques of today can help us explore the past.

Michael Kent from Library and Archives Canada explores the history and documents found in the repositories of Jewish synagogues and cemeteries in Ottawa and around the world.

On September 14, 2020, Michael Kent, Curator of the Jacob M. Lowy Collection at Library and Archives Canada, spoke to members of the Historical Society of Ottawa and guests via our first ever “Zoom” presentation. Michael’s fascinating presentation explored the hidden treasures of the Geniza in Ottawa and around the world. The “Geniza” is the sacred storage area in a synagogue or cemetery used for the disposal of worn-out religious books and papers.

Hon. Alexander Mackenize

The Hon. Alexander Mackenzie was Canada’s second Prime Minister, serving from 1873-78. Mackenzie was Leader of the Opposition until 1880 and then continued to sit as a Liberal MP until April 17, 1892 when he died from a stroke after suffering a fall at the age of 70.

This video was prepared for the Historical Society to celebrate Canada 150 and to raise awareness and appreciation of Mackenzie's life and times and contributions to Canada.

Funeral of Sir Wilfrid Laurier

The view in front of the Notre Dame Cathedral Basilica in Ottawa on Sussex Drive on 22 February 1919, Library and Archives Canada IDC: 94473

1920 - Film sequence from a visit to Ottawa

The film shows a woman receiving a letter from woman friend in Halifax followed by this friend arriving at the train station in Ottawa and being taken on a tour of the city in a convertible car.

1938 - Ottawa: Canada's Capital,

Library and Archives Canada

1939 - Royal Banners Over Ottawa

Visit to Ottawa by George VI and Queen Elizabeth

1940 - Odds and ends

from old footage of Ottawa

1941 - Ottawa on the River

A film about Ottawa in 1941

1946 - Byward Market

When Ottawa's Byward Market was a real market.

1968 - Touring Ottawa

Amateur film of from Maitland Avenue along the Queensway to downtown, around Parliament, to Champlain point, along the Ottawa River, Dows Lake and many other places in town.

Local History Websites

This is an incomplete list of online sites that focus on Ottawa history. The Historical Society of Ottawa does not necessarily subscribe to the views expressed in these blogs, nor can it attest to their accuracy. The responsibility for the content of the websites remains with their authors.

Britannia, A History

"This site is about the community of Britannia in Ottawa, Canada. It is mostly about the history, but ... [i]t is incomplete and always will be. ... Really it is more like an encyclopedia of Britannia; a collection of articles and information, not a single, continuous story."

Capital Chronicles | History of the National Capital

"The History You Were Never Told" as recounted by Rick Henderson.

Capital History

Carleton’s Centre for Public History explores histories about people, places, and events in Ottawa’s National Capital Region. An ongoing history and heritage project that links Ottawa history with the city’s built environment.

Civic Hospital Neighbourhood

Documenting the community’s transition from forest and farmland to today’s urban environment.

Colin Churcher’s Railway Pages

"Welcome to my home page. I live in Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. I have been interested in railways for many years and have been fortunate to pursue a career in railways. In these pages I will be setting out various aspects of my interest."

French Life in the Capital

This exhibition brings to light significant events in the capital’s history where Francophones have helped shape the face of Ottawa.

A History of Ottawa East

"Published May, 2004 by the Old Ottawa East Community Association. Written in part and compiled by Rick Wallace. Technical Direction by David Walker"

House History Ottawa - A project by M.S. Lowell and D. Lafranchise

"M.S. Lowell, (1961-) started doing house histories in 1989. He has conducted 23 various Ottawa House History projects in the past 15 years. Marc is originally from Toronto and is self-taught. Marc has also done work in geneaolgy. He is listed on the Library and Archives Canada Freelance Researchers list. D. Lafranchise (1952-) is a retired Civil Servant from Ottawa who has a major interest in Ottawa History."

The Kitchissippi Museum

A blog about west Ottawa's little-known history, with stories, photos and information covering the fascinating history of the historic Kitchissippi neighbourhoods.

Lebreton Flats Remembered

"Reflections on the history of a vanished community. Our mission, rekindle memories of a lost legacy."

Lost Ottawa

"Lost Ottawa is a Facebook research community devoted to images of Ottawa and the Outaouais up to the year 2000. Anyone can join. Just "Like" the page."

Ottawa's Bygone Buildings

Through the years, Ottawa has seen many buildings come and go. Some were lost to fire, some demolished for the expansion of parkland, roads and other improvements while others were removed to make way for newer buildings.

This project includes an online map showing the outline footprint of buildings which existed in 1912 but no longer exist today. Each footprint contains information and photos of these buildings.

Ottawa Family Tree

"When Jean Cadieux, a locksmith, made his way from Luché, in the Loire Valley of France to Montréal, during 1653, the first of my ancestors set foot upon the North American continent. It was a wild ride .. literally! .. from then, as the fur trader Antoine Cadieux made his way across the rapids of the Ottawa River before settling down with a family in Quyon, QC. This blog pays tribute to these ancestors’ courage and daring under the rubric that every family’s story is worth telling and ought to be passed along! The purpose of this blog is to share across the internet information on the O’Connor, Doyle, Dolan, Killeen, Kelly, O’Callaghan, Cadieux, Frood, Wilson and McEwan families found in researching the family tree."

Ottawahh

A personal blog with many descriptions and historical photographs of Ottawa's past.

Ottawa Past and Present

"A few decades ago, Ottawa was drastically different: Sparks Street was thriving, people were actually living downtown and at LeBreton Flats and a train could bring you to the heart of the city. The narrow and institutionalized vision of bureaucrats, the rapid expansion of car use, and a generalized neglect of architectural heritage changed the urban fabric of the Capital. The Gréber Plan and the NCC transformed Ottawa for the worse. One building at a time. We promote intensification and discourage sprawl. We are not against tall buildings, but we have a lot to say about bad design. This website is not strictly about heritage preservation, but rather what goes down the drain when those older buildings are demolished and streets are denatured."

Ottawa Police Service - Lives Tragically Lost in the Line of Duty

Follow this link as we join in honouring those police officers who made the ultimate sacrifice while working to keep Ottawa’s streets safe.

Ottawa Rewind

"Hello, welcome to Ottawa Rewind, a blog dedicated to stories that I think are pretty cool about Ottawa and the surrounding area. Pull up a chair, grab a drink and enjoy the ride as we rewind some time…"

Ottawa Start: History

"Photographs of Ottawa that capture the way of life up to about 1970. Much of the city has changed over time with growth and loss of heritage and street life"

Sandy Hill Stories

by François Bregha — Sandy Hill has a rich history that can still be seen in many of the mansions that grace the neighbourhood or in street names that recall former activities.

Stanley Brede

Photographer and cinematographer who was stationed at Rockcliffe with the Royal Canadian Air Force during WWII and had a long career with Crawley Films, Ottawa.

The Margins of History

A personal ramble through the history of Ottawa.

Today in Ottawa’s History

"The purpose of this blog is to provide readers with a brief account of an interesting or important event that happened in Ottawa’s history on a given day of the year. Ultimately, my objective is to have an article for every day of the year. While I will try to cover the highlights of each event, the brevity of the articles precludes a lot of detail and analysis. If readers wish to explore a topic in more detail, the sources listed at the end of each story will provide a useful starting point for research."

Urbsite

A blog on a variety of Ottawa historical topics.

Vanished Ottawa

A blog on abandoned buildings, fading buildings and buildings long gone from Ottawa.

Vintage Ottawa

"Nostalgic look at Ottawa's past be it buildings, people, events, houses or more."

Workers' History Museum

Dedicated to the development and preservation of workers’ history and heritage in the National Capital Region and Ottawa Valley with a goal to present, promote, interpret, and preserve workers’ history, heritage, and culture.

Focus on Heritage

Canadian National Digital Heritage Index (The)

"The Canadian National Digital Heritage Index (CNDHI) is an index of digitized Canadian heritage collections located at Canadian universities and provincial and territorial libraries. Supported by funding from Library and Archives Canada and the Canadian Research Knowledge Network, CNDHI is designed to increase awareness of, and access to digital heritage collections in Canada, to support the academic research enterprise and to facilitate information sharing within the Canadian documentary heritage community."

Canadiana Collections

"With the support of major memory institutions, CRKN identifies, catalogues, and digitizes documentary heritage—books, newspapers, periodicals, images and nationally-significant archival materials—in specialized searchable databases."

CBC Historical Archives

"The CBC Archives is a unique collaboration of creative teams in Toronto working together with archivists and educational writers across Canada."

Capital Heritage Connexion

The Capital Heritage Connexion/Patrimoine de la Capitale is an umbrella organization serving heritage stakeholders in Canada’s Capital area. The CHC plays a leading role in developing and sustaining Ottawa’s heritage sector and ensuring local residents have access to heritage.

City of Ottawa Archives

"Discover Ottawa's hidden treasures. Explore more than three million photographs, research your home or family and bring the past into the present. The caretakers of Ottawa’s documentary history, the City of Ottawa Archives, are mandated to preserve original documents on behalf of past and future generations. Ottawa’s history lives here. Uncover and discover for yourself."

Cumberland Township Historical Society

The Cumberland Township Historical Society is a non-profit, volunteer and community-based organization whose goal is to preserve Cumberland Township history.

Gloucester Historical Society

"An organization for preserving and promoting the history of the former Gloucester Township."

Glengarry History

"Glengarry History has been formed ... with the intent of acting as a liaison and partnership group for other organizations active in the area of preserving the history of Glengarry."

Goulbourn Township Historical Society

"Welcome to the Goulbourn Township Historical Society – a community group dedicated to the history of the former Goulbourn Township, now amalgamated into the City of Ottawa in Ontario, Canada.If you have ties with Goulbourn, or are interested in history generally, you might Richmond-Fair-2010 for webwant to join us."

Heritage Ottawa

"We are a group of dedicated volunteers who are passionate in our commitment to promote awareness, appreciation and preservation of outstanding examples of historic buildings and places in Ottawa and the National Capital Region."

Huntley Township Historical Society

"The Huntley Township Historical Society was formed in 1985 ... [t]o collect historical and genealogical material and establish a repository of information and artifacts on the former Huntley Township for research purposes and as a contribution to Canadian history, and to publish and display related materials."

Library and Archives Canada

Library and Archives Canada’s "mandate is as follows: to preserve the documentary heritage of Canada for the benefit of present and future generations; to be a source of enduring knowledge accessible to all, contributing to the cultural, social and economic advancement of Canada as a free and democratic society; to facilitate in Canada co-operation among communities involved in the acquisition, preservation and diffusion of knowledge; to serve as the continuing memory of the Government of Canada and its institutions."

Ottawa Public Library Ottawa Room

A centralized information resource about Ottawa and surrounding areas, both past and present, that helps preserve Ottawa’s written heritage for researchers and for residents with a passion for local history. The collection includes over 15,000 items that can be consulted free of charge. Main Library, 3rd floor.

Ottawa South History Project

"We are a group of local amateur historians whose interest is to research, document, and present facts and information about the history of Old Ottawa South in a fun and informative way."

The Rideau Canal

"is a non-commercial site run (and paid for) on a hobby basis by Ken Watson."

The Rideau Township Historical Society

"Preserving and promoting local history for the former Rideau Township."

Books

On occasion, the Society publishes substantive research in the form of a book.

Prices of books vary — as shown below — and the cost of postage is extra.

To order, please contact the Historical Society of Ottawa by mail or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Looking for more local history books? Check out these titles available from the Cumberland Township Historical Society.

The Return of "D" Company

3 November 1900

It is said that Canada became a nation at the Battle of Vimy Ridge in April 1917 during World War I when the Canadian Expeditionary Force took the German-held high ground amidst fierce fighting—an achievement that had eluded British and French forces in three years of fighting. Although there is no disputing the heroism and the accomplishment of the Canadian soldiers, some historians maintain that the significance given to Vimy Ridge in the development of Canadian nationalism is a modern invention. It also overlooks the impact of an earlier war on Canadian national confidence. That war was the South African War, also known as the Boer War.

The Boer War was a nasty colonial conflict that pitted Britain against two Boer (Afrikaans for farmer) republics called the South African Republic, also known as the Transvaal, and the Orange Free State. There were actually two wars. The first, in which the British got a drubbing, lasted from 1880 to 1881, while the second more famous one lasted from 1899 to 1902. The wars resulted from British imperial designs over southern Africa butting up against the desire by Boer settlers for their own independent, white republics. Thrown into the mix was the discovery of gold in Boer territories, an influx of foreign, mostly British prospectors and miners (called uitlanders) who were denied political rights by Boer governments who feared being swamped by the incomers, rival British and Boer economic interests, British fears of German interference in southern Africa, and the ambitions of Cecil Rhodes, the premier of the Cape Colony from 1890 to 1896.

The South African war began in October 1899 after talks between the British government and the Boer governments failed. Boer soldiers invaded the British Natal and Cape Colonies and subsequently laid siege to ill-prepared British troops at Ladysmith, Mafeking, and Kimberly. The attacks galvanized pro-British sympathies throughout the Empire, whipped up by nationalistic newspapers. Australia and New Zealand sent troops to assist the Mother Country in its hour of need.

In Canada, public opinion in English Canada was likewise strongly in favour of Britain and the uitlanders. The Ottawa Evening Journal said “Britain, a democratic monarchy, is at war with a despotic republic, and seeks to give equality to the people of the Transvaal.” Pressured by English Canada, the Liberal government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier agreed to send 1,000 volunteers to support the British cause over the opposition of many French Canadians including fellow Liberal party member Henri Bourassa, who resigned his federal seat in protest. Bourassa later founded the newspaper Le Devoir. This was the first time Canada had committed troops to an overseas war. In 1884, Canadian volunteers, many from the Ottawa area, had agreed to serve as non-combatants in the relief of “Chinese” Gordon at Khartoum, Sudan.

In Ottawa, imperial sentiment was strong, even reportedly among its francophone population. One such resident opined that “French Canadians had no reason to be other than loyal to England…England had dealt fairly with us and we should be unhesitatingly be loyal.” Another said “Every British subject, whether of French or any other extraction, should be willing to bear the responsibilities of Empire.” Of the first 1,000 volunteers to serve in South Africa in the 2nd Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry under the command of Colonel Otter, sixty-seven came from the Ottawa area.

The Ottawa contingent, “D Company,” left the Capital for Quebec City by train in late October 1899 under the command of Captain Rogers, formerly Major Rogers of the 43rd Regiment based in Ottawa. Rogers had served with distinction in the North-West Rebellion. A crowd of 30,000 saw the volunteers off “to defend the honour of Britain.”

Many Ottawa residents took a special train to Quebec City to see their boys off on the Sardinian for South Africa on 30 October 1899. The Journal was moved by the occasion to write: “Descendants of the men who fought with Montcalm and Wolfe marched side by side to play their part in the great South African drama.” Before boarding the ship, the Canadian contingent was fêted at the Quebec City Drill Hall. The Ottawa volunteers cheered “Hobble, gobble, Razzle, dazzle, Sis boom bah, Ottawa, Ottawa, Rah. Rah. Rah.” as if they were going to a football game.

Over the next year, the soldiers of the Canadian contingent proved in battle that they were second to none. The Canadians distinguished themselves at the Battle of Paardeberg where after nine days of bloody fighting in late February 1900, British forces defeated a Boer army. It was their first major victory of the war. The Boer general, Piet Cronjé, surrendered when his soldiers woke to find themselves facing Canadian rifles from nearly point blank range. In the dead of night, the Canadian troops had silently dug trenches on the high ground overlooking the Boer line. In the fighting, the British forces sustained more than 1,400 casualties, of which 348 men died. Thirty-one Canadian soldiers lost their lives in the battle, including two Ottawa men. Many more were wounded. Boer losses amounted 350 killed or wounded and 4,019 captured. Canadian forces subsequently distinguished themselves in the capture of the Transvaal capital, Pretoria.

Crowds welcoming home Ottawa's "D" Company at the Canada Atlantic Railway Company's Elgin Street Train Station

Crowds welcoming home Ottawa's "D" Company at the Canada Atlantic Railway Company's Elgin Street Train Station

Library and Archives Canada, C-007978After completing their one year tour of duty, the first Canadian contingent to fight in the South Africa War returned home aboard the transport ship Idaho. The men were paid off in Halifax with the government also providing them new winter clothes. A special train then carried the veterans westward, dropping off soldiers along the way. Many had brought mementoes home. One man carried a little monkey on his shoulder while another had a parrot in a wooden box. Captain Rogers of Ottawa’s “D” Company brought home a Spitz dog from Cape Town. With the Idaho having stopped in St Helena on the way to Canada, another officer brought home sprigs of the willow trees that grew at Napoleon Bonaparte’s grave.

Thirty-one Ottawa veterans arrived home at 2.45pm on Saturday, 3 November 1900. The famed “Confederation poet,” W. Wilfred Campbell, who lived in Ottawa, penned a poem to welcome them. Titled Return of the Troops, the first verse went:

Canadian heroes hailing home, War-worn and tempest smitten, Who circled leagues of rolling foam, To hold the earth for Britain.

The return of “D” Company was signalled by the ringing of the City Hall bell, a refrain that was taken up by church bells across the city. More than 40,000 flag-waving citizens were in the streets to watch their heroes arrive at the Elgin Street station and march to Parliament Hill to the tunes of Rule Britannia and Soldiers of the Queen. They were joined by other South African veterans who had been invalided home earlier. In the parade were elements of all regiments based in Ottawa, including the 43rd Regiment, the Dragoon Guards, the Field Battery, the Governor General’s Foot Guards and the Army Medical Corps. The parade was led by members of the police force, on foot, horse, and bicycle to clear the streets of well-wishers, followed by members of the reception committee. Also present were veterans of the 1866 and 1870 Fenian raids.

Return of "D" Company, Parade along Wellington Street, 3 November 1900

Return of "D" Company, Parade along Wellington Street, 3 November 1900

Library and Archives Canada, C-002067Along the parade route, homes and stores were bedecked with flags, bunting and streamers. Store fronts and window displays were also decorated in patriotic themes. In the window of George Blyth & Son was a figure of Queen Victoria in a triumphal arch with two khaki-clad soldiers standing in salute. In the background was a canvas tent. The words “Soldiers of the Queen” were written in roses in the foreground. Ross & Company displayed a crowned figure with a sceptre in her hand being saluted by two sailors. R.J. Devlin’s and R. Masson’s stores were lit with electrical lights with Queen Victoria’s cypher, “V.R.” displayed over their doors in large letters. The Ottawa Electric Company building on the corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets was draped in bunting, flags and strands of electric lights. Above the main entrance there was a large maple leaf and beaver in coloured lights. Not to be left out, the usually staid citizens of Ottawa were also patriotically dressed. Women wore little flags in the hats while young men had flags for vests.

"D" Company parading in front of the central block on Parliament Hill, 3 November 1900

"D" Company parading in front of the central block on Parliament Hill, 3 November 1900

Library and Archives Canada, Mikkan No. 3407088Parliament Hill was decorated to greet the return of “D” Company. The central block was ornamented by two large pictures picked out in electric lights on either side of the main entrance. On the left was a soldier charging with a rifle in hand with the word “Paardeberg” underneath. On the right was a trooper on horseback with the word “Pretoria,” underneath. Other emblems mounted on the towers included “VRI,” which stood for Victoria Regina Imperatrix, over the main entrance, as well as a crown, maple leaf and beaver. All were illuminated with electric lights. Strings of lights also stretched from the Victoria Tower in the centre of the main block to the east and west corners of the building.

The returning soldiers marched in the khaki uniforms that they had worn in South Africa. As they passed by the cheering multitudes, men from the crowd jumped into the ranks to shake the hand of a friend or family member. At times the police had difficulty in controlling the seething crowd. The Journal reported that on a couple of occasions, “the police, without warning, caught the eager relative of the long-absent warrior by the throat and hurled him back into the crowd.”

On Parliament Hill, the veterans were welcomed home by Lord Minto, the Governor General, who told the troops that he was proud “to be able to receive the Ottawa contingent into the Capital of the Dominion, the Ottawa representatives of the regiment that won glory for Canada at Paardeberg.” He then read out a message of thanks from Queen Victoria. This was followed by speeches from the Hon. W. R. Scott, secretary of state, and Ottawa’s Mayor Payment.

Ottawa sparkled that night. In addition to the lights on Parliament Hill that scintillated like diamonds, Sparks Street was ablaze with strings of Chinese lanterns strung across the road from Bank Street to Sappers’ Bridge. Electric lights illuminated Wellington Street. The words “Our Boys,” and “Welcome Home” were written in lights on the Victoria Chambers and the Bank of Montreal buildings.

The following Monday evening, another reception was held in honour of returning heroes at Lansdowne Park in the Aberdeen Pavilion. Close to ten thousand people cheered the Ottawa veterans. The biggest cheer was reserved for Private R. R. Thompson who had received the “Queen’s scarf” for bravery. The scarf was one of eight personally crocheted by Queen Victoria to be awarded to private soldiers for outstanding bravery in the South African conflict. Thompson had received his award for aiding wounded comrades at Paardeberg.

Boer War statue honouring Ottawa soldiers who died in the South African War once stood on Elgin Street in front of the City Hall which burnt down in 1931. It currently stands in Confederation Park

Boer War statue honouring Ottawa soldiers who died in the South African War once stood on Elgin Street in front of the City Hall which burnt down in 1931. It currently stands in Confederation Park

Topley Studios, Library and Archives Canada, PA-008912Canadians everywhere basked in the reflected glory of their returning heroes from the South Africa War with celebrations across the country. Canada had done its part in preserving the honour of Queen and Empire. Moreover, Canadian soldiers were seen as equals of the finest in the British Army. The Journal wrote: “One year ago they left a country that was little known to the world, save as a prosperous colony; only one year, and they returned to find a nation; a nation glorying in its newly acquired honor, and a nation that does them homage as the purchasers of that honor.” In an editorial titled Patriotism and Loyalty, the newspaper added that “Canadians have always been both patriotic and loyal to the Mother Country.” But now “the fruits of confederation have suddenly ripened, and we have begun to feel our nation-hood.”

Canadian soldiers subsequently gained distinction in later battles in South Africa, including at Leliefontein and Boschbult. Four Canadians received the Victoria Cross for valour during the war. In total, more than 7,000 Canadian soldiers and twelve nurses volunteered to serve in South Africa, of whom 267 died and whose names are recorded in the Book of Remembrance of the Canadian service personnel who have given their lives since Confederation while serving their country. In Ottawa, 30,000 children donated their allowances to build a statue to honour the sixteen Ottawa volunteers who died in the conflict.

After the Imperial forces defeated Boer armies on the field in 1900, the Boers resorted to guerrilla warfare for the next two years before surrendering. The British responded with a scorched earth policy and placed Boer women and children in concentration camps. Owing to neglect and disease due to overcrowding, tens of thousands of civilians died. Non-combatant deaths exceeded 43,000 including Afrikaaner women and children and black Africans. More than 22,000 British and allied soldiers died in the three-year conflict, while suffering a similar number of wounded. Boer military deaths numbered more than 6,000.

Sources:

BBC. 2010. “Second Boer War records database goes online,” 24 June.

Canadian War Museum, 2017. Canada & The South African War, 1899-1902.

Evening Citizen (The), 1900. “The Canadians Are At Halifax,” 1 November.

————————–, 1900. “The Boys Will Be Here On Time,” 3 November.

————————–, 1900. “It Was A Right Royal Welcome They Received,” 5 November.

————————–, 1900. “Form Paardeberg to Pretoria,” 5 November.

Evening Journal (The), 1899. “A Canadian Contingent,” 13 October.

————————————-, 1899. “Have Gone to Defend the Honor of Britain,” 25 October.

————————————-, 1900. “With the Ottawa Boys Down at the Citadel,” 30 October.

————————————-, 1900. “Return of “D” Company, 3 November.

————————————-, 1900. “Return of the Troops,” 3 November.

————————————-, 1900. “Patriotism and Loyalty,” 5 November.

————————————-, 1900, “Forty Thousand Glad Acclaims to Ottawa’s Brave Soldiers. 5 November.

————————————-, 1900. “Gold lockets Given to Ottawa’s Gallant Soldiers,” 6 November.

McKay, Ian & Swift, Jamie, 2016. The Vimy Trap: Or, How We Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Great War, Toronto: Between the Lines.

Miller, Carmen & Foot, Richard, 2016. “Canada and the South African War,” Historica Canada.

New Zealand History, 2017. South African War.

Pretorius, Fransjohan, 2014. “The Boer Wars,” BBC.

South African History Online, 2017. Second Anglo-Boer War, 1899-1902.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

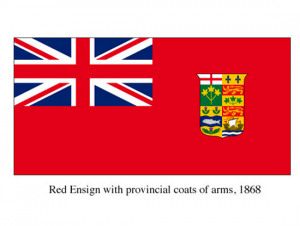

Vexing Vexillology

Of course, views evolved and shifted over time. During the early, uncertain years immediately after Confederation, support for the British connection was very strong, politically and emotionally. With the United States casting an avaricious eye northwards, you can appreciate this sentiment. Even Quebecers were content to live under the British flag, in a land that provided a constitutional guarantee for their religious and linguistic rights. The flag most commonly, but unofficially, flown at that time was the British Red Ensign with the provincial shields of the four founding provinces on the fly. As additional provinces joined Confederation, their arms were added.

While a Red Ensign with a Canadian coat of arms on the fly was approved by the British Admiralty for use by Canadian-registered ships in 1902, at home things seemed to go backwards. The federal government began flying the Union Flag, or Jack, over Parliament Hill after the Boer War reflecting the prevailing strong imperial feelings. But nationalist sentiment surged during World War I. Although Canadian soldiers fought under the Union Flag, they were identified by a maple leaf emblem on their uniforms. With Canada coming of age on the battlefield, and amidst growing national confidence, there was heightened interest in developing a distinctive Canadian flag. In 1922, the government of Mackenzie King replaced the provincial crests on the Red Ensign with the arms of Canada. Two years later, this new Canadian Red Ensign was authorized for use abroad to help identify Canadian foreign legations. However, the Union Flag continued to fly at home.

Canadian Red Ensign used from 1922-1957. In 1957, the colour of the maple leaves was changed to red.The first flag debate started innocuously. In 1925, the Department of National Defence, noting that the Canadian Red Ensign was used on Canadian-registered ships and at overseas legations, asked for something distinctive to fly at home. King set up a committee of civil servants to come up with something. When news leaked to the press, a firestorm of opposition was ignited, especially in loyalist Ontario. Demands were made for a parliamentary resolution to confirm the Union Flag as the only official Canadian flag. Heading a minority government, King wilted under the pressure. Disbanding the flag committee, he said that there would be no change in flag unless sanctioned by Parliament.

Canadian Red Ensign used from 1922-1957. In 1957, the colour of the maple leaves was changed to red.The first flag debate started innocuously. In 1925, the Department of National Defence, noting that the Canadian Red Ensign was used on Canadian-registered ships and at overseas legations, asked for something distinctive to fly at home. King set up a committee of civil servants to come up with something. When news leaked to the press, a firestorm of opposition was ignited, especially in loyalist Ontario. Demands were made for a parliamentary resolution to confirm the Union Flag as the only official Canadian flag. Heading a minority government, King wilted under the pressure. Disbanding the flag committee, he said that there would be no change in flag unless sanctioned by Parliament.

The Statute of Westminster which effectively gave Canada its independence in 1931 spurred renewed efforts to design a national flag. World War II provided an additional fillip as Canadian servicemen abroad strongly favoured fighting under distinctive Canadian symbols. When Prime Minister King met Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt in Quebec City in 1943 to plan the invasion of Nazi-occupied Europe, the Canadian Red Ensign flew proudly between Britain’s Union Flag and the American Stars and Stripes over La Citadelle. The following year, the Canadian Red Ensign was authorized for use by the Canadian Army on land. It temporarily replaced the Union Flag on the Peace Tower at Parliament Hill on Victory-in-Europe Day (8 May 1945), and became a permanent fixture there following an order-in-council on 5 September 1945.

Proposed Flag, 1946Late in 1945, King tried again to come up with a new national flag. A committee examined roughly 2,700 designs submitted by the general public, the majority of which featured some sort of maple leaf motif. But the committee, like its 1920s’ predecessor, struggled to find a compromise between nationalists and imperialists. A vocal minority demanded the Union Flag to be retained. The committee finally agreed to a modest change—the Red Ensign adorned with a gold maple leaf instead of the Canadian arms on the fly. Although it received King’s approval, it didn’t go over well among nationalists both inside and outside Quebec who wanted to eliminate all foreign symbols. With the country still divided, the flag issue returned to the back burner and left to simmer for another twenty years.

Proposed Flag, 1946Late in 1945, King tried again to come up with a new national flag. A committee examined roughly 2,700 designs submitted by the general public, the majority of which featured some sort of maple leaf motif. But the committee, like its 1920s’ predecessor, struggled to find a compromise between nationalists and imperialists. A vocal minority demanded the Union Flag to be retained. The committee finally agreed to a modest change—the Red Ensign adorned with a gold maple leaf instead of the Canadian arms on the fly. Although it received King’s approval, it didn’t go over well among nationalists both inside and outside Quebec who wanted to eliminate all foreign symbols. With the country still divided, the flag issue returned to the back burner and left to simmer for another twenty years.

The great flag debate of 1963-64 pitted Lester B. Pearson against John G. Diefenbaker. Pearson, at the head of a minority Liberal government, promised that Canada would have a new flag in time for its 1967 centennial. His point man on the flag issue was John Matheson, the Liberal MP for Leeds. Drawing on earlier maple-leaf proposals, and using the red and white colours of Canada proclaimed by King George V in 1921, he suggested a design of three red maple leaves on a white field. Matheson’s simple but striking proposal was subsequently modified by designer Allan Beddoe who added two vertical blue bars on either side to represent the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. A delighted Pearson presented this design to Parliament in June 1964.

The "Pearson Pennant," 1964

The "Pearson Pennant," 1964  Flag of Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario As in the past, the country was riven over the flag question. Diefenbaker, the old Conservative who cherished the imperial connection, fought tooth and nail against what he derisively called the “Pearson pennant.” Canadian veterans, who favoured retaining the Canadian Red Ensign, booed and hissed at Pearson when the prime minister came to address the Winnipeg Legion in May 1964. But a majority of Canadian were ready for change. A special 15-member committee, chaired by Herman Batten, was given the herculean task of finding a new flag. After gruelling discussions and the consideration of roughly 3,500 suggestions sent in by Canadians, three design archetypes made the finals: a flag containing the Union Flag or fleur-de-lys, a three-leaf flag represented by the Pearson pennant, and a one-leaf flag represented by the red and white maple leaf flag. The third design was inspired by the flag of the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario. In March 1964, Col. George Stanley, the Dean of Arts at RMC, suggested to John Matheson that the RMC’s red and white flag might make a suitable national standard if the RMC crest were replaced with a red maple leaf. With a little tweaking of the design to enlarge the white central panel to better display the single, eleven-point red maple leaf of designer Jacques St. Cyr, our flag was conceived.

Flag of Royal Military College, Kingston, Ontario As in the past, the country was riven over the flag question. Diefenbaker, the old Conservative who cherished the imperial connection, fought tooth and nail against what he derisively called the “Pearson pennant.” Canadian veterans, who favoured retaining the Canadian Red Ensign, booed and hissed at Pearson when the prime minister came to address the Winnipeg Legion in May 1964. But a majority of Canadian were ready for change. A special 15-member committee, chaired by Herman Batten, was given the herculean task of finding a new flag. After gruelling discussions and the consideration of roughly 3,500 suggestions sent in by Canadians, three design archetypes made the finals: a flag containing the Union Flag or fleur-de-lys, a three-leaf flag represented by the Pearson pennant, and a one-leaf flag represented by the red and white maple leaf flag. The third design was inspired by the flag of the Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario. In March 1964, Col. George Stanley, the Dean of Arts at RMC, suggested to John Matheson that the RMC’s red and white flag might make a suitable national standard if the RMC crest were replaced with a red maple leaf. With a little tweaking of the design to enlarge the white central panel to better display the single, eleven-point red maple leaf of designer Jacques St. Cyr, our flag was conceived.

When the committee came to choose among the designs, Matheson outmanoeuvred the Conservatives. On a series of votes, the Canadian red ensign was eliminated, as was any new design containing the Union Flag or fleu-de-lys. That left in contention the Prime Minister’s three-leaf flag and Col. Stanley’s one-leaf flag. Expecting the Liberals to support their leader’s cherished “pennant,” the Conservatives voted for the one-leaf flag. But Matheson, realizing that Pearson’s choice was a non-starter, had already solicited the other members’ support for the one-leaf design. When the secret ballots were tallied on 22 October 1964, Conservative members were horrified to discover that it was a unanimous committee decision for the red and white, single-leaf flag.

The Maple Leaf flag flies for the first time, 15 February 1965The kicking and screaming continued in the House of Commons for the next two months but this time the end was in sight. After closure was applied to limit debate, weary MPs voted 163-78 for the single-leaf design at 2:00am on 15 December 1964. Two days later the Senate passed the necessary legislation, and on 24 December Queen Elizabeth gave her approval. A Royal Proclamation, describing Canada’s new flag in appropriate heraldic terms, was released on 28 January 1965.

The Maple Leaf flag flies for the first time, 15 February 1965The kicking and screaming continued in the House of Commons for the next two months but this time the end was in sight. After closure was applied to limit debate, weary MPs voted 163-78 for the single-leaf design at 2:00am on 15 December 1964. Two days later the Senate passed the necessary legislation, and on 24 December Queen Elizabeth gave her approval. A Royal Proclamation, describing Canada’s new flag in appropriate heraldic terms, was released on 28 January 1965.

At noon, on 15 February 1965, in front of a crowd of 10,000 on Parliament Hill and in the presence of the Governor General, Georges Vanier, Prime Minister Pearson, and an unhappy Diefenbaker, RCMP constable Gaetan Secours lowered the old Canadian Red Ensign for the last time and raised Canada’s new national standard. As the Governor General’s flag was flying on top of the Peace Tower as protocol demanded, our new national flag was raised on a temporary flagstaff set up specially for the occasion. When it reached the top of the pole, a timely puff of wind unfurled our now much-beloved, red and white, Maple Leaf Flag for all to see. Canada’s official national flag was born.

Sources:

Archbold, Rick, 2014. A Flag for Canada.

Canada Heritage, 2014. Birth of the National Flag of Canada.

CBC, 2001. The Great Flag Debate.

Fraser, Alistair B., 1998. The Flags of Canada.

Le Citoyen, 1964. “Enfin! Un drapeau canadien,” 16 décembre.

The Globe and Mail, 1964. “Pearson Booed, Hissed Over Maple Leaf Flag,” 18 May.

——————–, 1965. “Pearson’s Address on the Maple Leaf Flag,” 16 February.

——————–, 1965, “PM Proclaims a New Era as Leaf Replaces Ensign,” 16 February.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1945. “Warm Debate In House On Contentious Canadian Flag Issue,” 9 November.

Le Salaberry, 1959. “Un drapeau canadien,” 22 janvier.

The Maple Leaf, 1945. “Canadian Flag,” 7 July 1945.

Yukon World, 1904. “The Canadian Flag,” 17 September.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.