Super User

Volunteers

Central to the life of The Historical Society of Ottawa is our volunteers. Being 100 per cent volunteer operated, the Society is totally dependent on its member volunteers for all facets of its operations. If you love history and would like to get involved, we have a job for you!

By volunteering with the Society, you will be helping to preserve and share Ottawa’s rich historical heritage. You will also be using your special skills, working with interesting people who share a passion for history.

Possibilities for helping are endless. We need people of diverse backgrounds and abilities for the Society to function effectively.

If you would like to get involved, or would like to find out more about volunteer opportunities with the Society, please contact us at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it., or speak to one of the Society’s directors.

We look forward to meeting you!

Patronage of Rideau Hall

Lady Minto

Lady Minto

Topley Studio, Library and Archives Canada, 3810248Since the founding of what was then called the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa in 1898, the Society has always had a close relationship with Rideau Hall There is a belief that Lady Aberdeen, the wife of the 7th Earl of Aberdeen who was Canada’s Governor General from 1893 to1898, was the Society’s first patron. However, while we know that she took a close interest in the fledgling organization, her patronage was likely unofficial as she and her husband returned to Britain just a few days after the first regular meeting of the Society.

For certain, Lady Minto, the wife of the 4th Earl of Minto who succeeded Lord Aberdeen, consented to become the patron of the Society in February 1899. For more than fifty years, the wives of succeeding Governors General continued this practice. In more recent decades, Governors General themselves have fulfilled this role, continuing a tradition of more than a hundred and twenty years of vice-regal patronage.

Special Events

Each year, the Historical Society of Ottawa organizes special outings for members and their guests to places of historical interest in Ottawa or in the Ottawa area. Typically, these outings consist of an animated tour or presentation by a local historian followed by a lunch. Should we be heading out of Ottawa, transportation is typically arranged, usually a tour bus with bathroom facilities.

The cost of the event varies, depending on entrance and other fees, and the cost of a bus if one is hired.

To allow persons on a budget to join the Historical Society of Ottawa and to participate fully in the Society’s activities, a Bursary Fund has been established to reduce membership fees and other expenses. If you are in this position, please contact the Society at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

These events are not only informative—a way of learning about Ottawa’s history close-up—but is a fun way of socializing with people who share your interest in history.

Recent Special Events

Community Talks

The Historical Society of Ottawa provides speakers on a range of Ottawa-related historical subjects. Our presentations are particularly suited to seniors and youth groups. There is no charge for this service.

Speakers and their areas of expertise include:

James Powell

Old Ottawa, Ottawa’s technological firsts, Lady Aberdeen, the 1939 Royal Visit, the Cold War, and Counterfeiting in Canada.

George Shirreff

Anything related to the history of film in Ottawa, and the Ottawa Little Theatre.

Speakers may be willing to present on other topics; they have an extensive knowledge of Ottawa history. So, if what you are looking for is not listed, please ask. It’s possible something could be organized.

To arrange for a speaker, please email The Historical Society of Ottawa at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Pamphlets

If you interested in having a more in-depth knowledge of Ottawa rich and diverse history, the HSO’ s Bytown Pamphlet series is for you!

Since the early 1980s, the Society has regularly published monographs on various aspects of Ottawa’s history. These monographs are available free to members and through the Ottawa Public Library, Library and Archives Canada, and the City of Ottawa Archives. We are currently in the process of scanning and digitizing all of our pamphlets to make them more accessible to the general public.

The first introductory pamphlet produced by the Historical Society of Ottawa contains excerpts from an address on the history of the Historical Society given by E.M. Taylor before the Ontario Genealogical Society (Ottawa Branch) on March 22, 1976.

Pamphlet Series

A number of the Society's pamphlets are available in digital format to download free of charge.

Heritage Events

Heritage Day

Heritage Day is part of Heritage Week, a nation-wide celebration that encourages all Canadians to explore their local heritage, to get involved with stewardship and advocacy groups, and to visit museums, archives, and places of significance. Heritage Day is a time to reflect on the achievements of past generations and to accept responsibility for protecting our heritage.

Ottawa Regional Heritage Fair

Aimed at students in Grades 4-10, the Fairs inspire young people to explore the many aspects of Canadian history, heritage and culture in a dynamic learning environment and to celebrate the results of their efforts at a public exhibition.

Colonel By Day

Colonel By Day takes place on the holiday Monday in August each year, close to the Colonel’s birth date of August 7, 1779. This popular summer event named in Colonel By’s honour celebrates Ottawa’s history and heritage with open air events, walking tours and a host of family friendly, heritage-themed activities.

BIFHSGO Annual Conference

"Genealogy always reminds me of a treasure hunt: we use our investigative skills to find the genealogical nuggets left behind about our ancestors. BIFHSGO’s annual conference provides a wonderful opportunity to advance one’s knowledge, expand one’s skills and meet a community of like-minded people."

– BIFHSGO Past President Duncan Monkhouse

“Hello Ottawa–Hello Montreal”

20 May 1920

At the turn of the twentieth century, radio was the new, cutting-edge technology. Building on the work of others, including Nikola Tesla, Édouard Branly, and Jagadish Bose, the Italian inventor Guglielmo Marconi established in the early years of the century a wireless telegraph system using a spark-gap transmitter that could send transatlantic radio messages in Morse code. The first such radio transmission, greetings from U.S. President Roosevelt to King Edward VII, was sent in 1903. Subsequently, ships began to be equipped with radio transmitters and receivers; radio distress signals sent by the RMS Titanic using Marconi equipment are credited with saving hundreds of lives in 1912. The Canadian inventor Reginald Fessenden demonstrated the feasibility of audio radio using continuous waves by sending a two-way voice message in 1906 between Machrihanish, Scotland and Brant Rock, Massachusetts. On Christmas Eve of that year, he broadcasted a short programme of music by Handel, his own rendition of some Christmas carols, and a reading from the Bible to ships at sea along the eastern seaboard of the United States from his Brant Rock base of operations. World War I brought further major technological advances, including the invention of the vacuum tube and the transceiver (a unit with both a radio transmitter and receiver), that spurred the development of commercial radio. By 1920, the world stood on the cusp of a new radio age with instantaneous, wireless, audio communication and entertainment.

On 19 May 1920, the Royal Society of Canada convened in Ottawa for its 39th Annual Meeting. The Society had been founded in 1882 with the patronage of the Governor General, the Marquis of Lorne, to promote scientific research in Canada. Society fellows gathered at the Victoria Memorial Museum for the opening of the conference, chaired by the Society’s president, Dr R. F. Ruttan of McGill University, and for the election of new fellows. They subsequently broke into specialist groups, to hear addresses on a variety of topics, including plant pathology, and the properties of super-conductors. That evening, President Ruttan gave the presidential address in the ballroom of the Château Laurier Hotel. The topic of his speech was “International Co-operation in Science.” The general public was cordially welcomed to attend this presentation, and another to be held the following evening at the same venue by Dr A.S. Eve, also of McGill University.

Dr Eve’s lecture commenced at 8.30pm on 20 May. Its intriguing title was “Some Great War Inventions.” Among the discoveries he discussed was the detection of submarines. Canadians had been on the forefront of this research, starting with Reginald Fessenden who pioneered underwater communications and echo-ranging to detect icebergs following the Titanic disaster. Subsequently, Canadian physicist Robert Boyle developed ASDIC in 1917, the first practical underwater sound detector machine, or sonar, for the Anti-Submarine Division of the Royal Navy. At the evening’s presentation, Dr Eve also demonstrated the advances made in the radio-telephone. At 9.44pm, the Society fellows and members of the public heard the words “Hello Ottawa—Hello Montreal” over a large loudspeaker called a “Magnavox,” set up in the Château Laurier’s ball room. The first public wireless conversation in Canada had begun.

For two days, engineers from the Canadian Marconi Company in Montreal and officers of the Naval Radio Station on Wellington Street in Ottawa had laboured to prepare for the event. The experimental radio station, located on the top floor of the Marconi building on William Street in Montreal, operated under the call letters “XWA” for “Experimental Wireless Apparatus.” It had first gone on the air on 1 December 1919 on an experimental basis. Another transmitting and receiver station was established at the Naval Radio Station, with a secondary receiving station set up at the Château Laurier, with an amplifier to ensure all attending Dr Eve’s presentation could hear the broadcast. At the Montreal end, Mr J. Cann, chief engineer for the Marconi Company, was in charge, while at the Naval Radio Station in Ottawa was Mr Arthur Runciman, also from the Marconi Company. Assisting Runciman were engineers, Mr D. Mason, and Mr J. Arial. Also present were Mr E. Hawken, the commanding officer of the Marine Department, and his wife. Stationed at the receiving station in the Château Laurier were Commander C. Edwards, director of the Canadian Radio Service and Lieutenant J. Thompson, his assistant. Journalists covering the historic radio broadcast were based at the Naval Radio Station.

Following the introductory exchange of words, the notes of “Dear Old Pal of Mine,” a 1918 hit song, sung by the Irish tenor John McCormick and played on a phonograph in Montreal, could be distinctly heard in Ottawa. This was followed by a one-step ballroom dance tune popular at the time. So well could the orchestra be heard, the Ottawa Journal reporter wrote that some of his colleagues listening to the broadcast at the Naval Station actually started an impromptu dance.

After the dance tune, one of the radio operators in Montreal delivered a speech prepared earlier by Dr Ruttan on behalf of the Royal Society of Ottawa in which he congratulated the Marconi Company and the Radio-Telegraph Branch of the Department of Naval Service for “their generous co-operation in this difficult scientific experiment.” Following a short pause, Society follows were treated to a live performance from Montreal of the early nineteenth century Irish folk ballad “Believe Me If All Those Endearing Young Charms,” written by the Irish poet Thomas Moore and sung by vocalist Dorothy Lutton. She sang a second song, “Merrily Shall I Live” as an encore.

It was then Ottawa’s turn to communicate to Montreal. The Ottawa operator first explained the radio experiment to his listeners. This was followed by Mr. E. Hawken singing the first verse of “Annie Laurie,” an old Scottish song that begins “Maxwelton’s braes are bonnie.” Receiving a wild round of applause from his Château Laurier audience, Hawken was persuaded to sing the second verse. Hawken’s performance was followed by the transmission of several dance tunes played on a phonograph. The evening’s programme concluded with hearty congratulations sent in both directions.

Dr Eve’s demonstration of radio telephony was deemed a huge success. The wireless operators in Ottawa and Montreal were elated. Never before had two-way radio communication had been achieved over such a long distance—110 miles (177 kilometres). The broadcast, at least at the Ottawa end, and especially at the Château Laurier where the signal was boosted by an amplifier, was generally clear and distinct. However, listeners at the Marconi station in Montreal had a more difficult time picking up the signal from Ottawa. Marconi officials explained that reception was adversely affected by interference from Montreal’s large buildings. There were apparently some tense minutes as Montreal listeners wearing headphones tried to decipher the sounds coming from the capital.

The broadcast launched Canada into the radio age. Some radio historians argue that the 20 May radio performance by Marconi’s XWA station to the Royal Society’s meeting in Ottawa was the first scheduled radio broadcast in Canada, and possibly the world. XWA became CFCF in November 1922. Reputedly, the call letters stood for “Canada’s First, Canada’s Finest.” The station’s call letters were changed to CIQC in 1991, and to CINW in 1999. The station went off the air in 2010.

Sources:

Broadcaster, 2001, 100 Years of Radio: Celebrating 100 years of radio broadcasting.

Historica Canada, Broadcasting.

The Citizen, 1920. “May Meeting of The Royal Society of Canada Opens,” 19 May.

The Gazette, 1920. “Wireless Concert Given For Ottawa,” Montreal, 21 May.

————–, 1920. “Heard In Ottawa.” Montreal, 21 May.

The Ottawa Journal, 1920. “Ottawa Hears Montreal Concert Over the Wireless Telephone, Experiment Complete Success,” 21 May.

Université de Sherbrooke, Bilan du Siècle, “Diffusion d’une émission radiophonique directe, ”.

Vipond, Mary, 1992. Listening In: The First Decade of Canadian Broadcasting, 1922-32, Carleton University Press: Ottawa.

Image: CFCF Radio, Montreal, author unknown, Université de Sherbrooke, Bilan du Siècle, “Diffusion d’une émission radiophonique directe,”.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Parking Meters Arrive in Ottawa

25 April 1958

By the time of the Great Depression the automobile had replaced the horse-drawn carriage. In 1929, five million cars were produced in the United States, with another quarter million made in Canada. City streets were becoming clogged with vehicles, and parking was becoming a serious problem everywhere. Through the working week, people drove their vehicles to downtown offices, and parked them on neighbouring streets for eight hours or longer. This left little room for shoppers. Although the Depression drastically slowed the production and sale of cars, it didn’t solve the parking problem. Carl C. Magee, a noted American publisher, came up with a solution–the coin-operated parking meter. (Magee had become prominent during the 1920s for publicizing the Teapot Dome Scandal, the biggest U.S. political scandal prior to Watergate, that led to the Secretary of the Interior being jailed for corruption.) Magee, in cono-operation with University of Oklahoma engineers Holger Thuesen and Gerald Hale, developed a working prototype. In May 1935, Magee filed a patent in the United States for a coin-controlled device, receiving U.S. patent 2,118,318 three years later for his invention. American cities took to the new invention like proverbial ducks to water as a way of encouraging motorists to vacate parking spaces. The fact that parking meters were a real money spinner certainly helped too. Meters paid for themselves in four or five months.

Parking meter image from Carl C. Magee's patent application for the coin operated parking meter filed 15 May 1935.

Parking meter image from Carl C. Magee's patent application for the coin operated parking meter filed 15 May 1935.

Patent received 24 May 1938, U.S. Patent OfficeOklahoma City installed Magee’s “park-o-meter” its streets in July 1935, just weeks after Magee filed his patent application. Reporting on the event, The Ottawa Journal called the new device the “automat of the curbstone,” describing it as “a metal hitching post with meter attached” that promised “to solve the pest of the streets – ‘the parking hog.’” It opined that people will be watching the experiment with great interest.

Ottawa wasted little time in exploring the possibility of introducing parking meters to the streets of the nation’s capital. In 1936, City Council received an offer from one O. G. O’Regan to install parking meters in downtown Ottawa. In a letter, O’Regan explained that the cost of the meters would be paid by parking fees, and that after the costs were met, the revenue would accrue to the city. Ottawa’s Board of Control said that O’Regan should speak to the Automobile Club, the Board of Trade and other groups to educate the public about such a drastic change in parking regulations. In an editorial the Journal said that the parking meter was “so new that probably many people are unfamiliar with it.” Assessing the pros and cons of a trial, the newspaper argued that if free street parking is not a “right,” then Ottawa might as well make some revenue from it “if the privilege is to be extended.” Also, if meters reduced casual parking, merchants might benefit. However, the newspaper was uncertain whether Ottawa citizens would take kindly to the idea, and wasn’t sure if meters could be used with parallel parking.

Ottawa did not take kindly to the idea. It took three attempts and twenty years before City Hall got the votes to install meters. On the first attempt in 1938, the Traffic Committee and the Board of Control recommended the installation of 903 meters in downtown Ottawa for a six-month trial period. Supporters of the measure hoped that meters would be more effective than existing parking regulations in curbing lengthy parking stays. In 1937, 14,000 parking tickets were handed out to motorists who had overstayed the 30-minute parking limit, but only 900 fines were issued. Opponents argued that instead of unsightly meters, parking problems could be addressed through the enforcement of existing rules. Mayor Stanley Lewis opposed meters as did merchants who feared losing business if free parking was eliminated. A concession on the part of meter supporters to reduce the charge for the first twelve minutes to only one cent was not sufficient to change minds. With Toronto and Montreal having turned down metered parking, Council rejected meters on an 18-8 vote. The measure was put onto the backburner for a decade.

Parking on Wellington Street in front of Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 1920s - already a problem. Notice the row of stately elm trees that lined the sidewalk. Sadly, they all succumbed to Dutch elm disease mid-century.

Parking on Wellington Street in front of Parliament Hill, Ottawa, 1920s - already a problem. Notice the row of stately elm trees that lined the sidewalk. Sadly, they all succumbed to Dutch elm disease mid-century.

Department of the Interior / Library and Archives Canada PA-034203In 1947, the issue resurfaced. By this time, meters had apparently been installed in 1,200 U.S. cities and 49 Canadian communities, including Kingston, Oshawa and Windsor. Once again, the Traffic Committee and the Board of Control favoured their introduction. But Stanley Lewis, who still occupied the mayor’s chair, remained a steadfast opponent. At Council, the debate was fierce. Supporters argued that metered parking would allow for a more equitable distribution of limited parking spaces, would speed up business, reduce congestion, and increase municipal revenues. The anti-meter faction argued that meters would ruin the look of Ottawa, would clutter sidewalks, and that shoppers would avoid areas that had metered parking. Some also contended that metered street parking was a “nuisance” tax on motorists, and that their advantages were unproven. One alderman suggested that to reduce congestion, he would ban all parking on Bank and Sparks Streets, and convert part of Major Hill’s Park into a parking lot. “The park is only frequented by tramps, and the public do not go there.”

In December 1947, Council narrowly voted (12-10) in favour of installing parking meters for a one-year trial, and issued a request for tenders. One would think that this would have been the end of the matter—far from it. Two firms, the Mi-Co Meter Company of Montreal and the Mark Time Meter Company of Ottawa, submitted bids for the contract. Early the following year, the Board of Control selected Mi-Co on the basis that it offered the lowest price. However, City Council subsequently rejected the Mi-Co bid in favour of Mark Time meters. While Council did not have to select the lowest bid, the rationale for overturning the Mi-Co bid was murky. The Mi-Co Meter Company, whose meters were actually made in Ottawa by a company called Instruments, Ltd, indicated that it would seek an injunction to stop the city from signing a contract with Mark Time on the grounds that it had won the tender since its meters were cheaper and conformed to City specifications whereas Mark Time meters did not. Among other things, the City had specified that the dial indicating the amount of time available was to be visible on both sides of the meter. This requirement that was not met by Mark Time meters. After another stormy Council session, Council voted 17-7 to rescind the awarding of the contract to Mark Time. It was a pyrrhic victory for Mi-Co. Ten days later City Council overturned the parking meter trial on an 18-2 vote. According to the Ottawa Journal, this decision “positively, definitively, officially and finally” meant that parking meters would not be installed on Ottawa streets.

With the parking debate in abeyance in Ottawa, Eastview (Vanier), which was a separate municipality, got a jump on its municipal big sister by introducing parking meters in May 1951 along Montreal Road. The charge was one cent for the first twelve minutes and five cents for an hour of parking time from 8am to 8pm Monday to Saturday. The experiment was a great success with congestion along Montreal Road substantially reduced. The fine for a parking violation was $1 if paid within 48 hours at the police station, or $3 if the infraction went to court.

Shortly afterwards, despite the “definitive” decision not to install parking meters in neighbouring Ottawa, the City Council’s Traffic Committee again recommended the installation of meters on certain Lowertown streets and well as on Lyon, Sparks and Queen Streets. But with Charlotte Whitton assuming the mayor’s chair in 1951, the recommendation went nowhere. The pugnacious and irascible Whitton was dead set against parking meters. “[If] we want space on our streets for moving traffic, we surely don’t want to rent out public streets and give people the right to store their cars there,” she said. She favoured more off-street parking instead.

It wasn’t until after Whitton had been dethroned in 1956 that the parking meter issue resurfaced in any significant manner at Ottawa City Council. By this time, meters had become a familiar part of the urban landscape in most North American towns and cities. Toronto had succumbed in 1952 and Montreal two years later. The Journal newspaper had also for several years run a series of favourable articles on the success of meters in other towns in curbing traffic congestion and, incidentally, raising huge sums for municipal coffers. These articles were helpful in preparing the ground for parking meters. In mid-December 1957, Ottawa’s Civic Traffic Committee unanimously recommended the installation of parking meters, the last outspoken critic of the machines on the Committee having thrown in the towel. A few days later, City Council passed the measure virtually without debate, agreeing to install meters in central Ottawa in the area bounded by Laurier, Kent, Wellington and Elgin as well as in Lowertown along Rideau from Mosgrove (located where Rideau Centre is today) to King Edward and along bordering side streets for one block.

To help avoid the contract problems that the City had ten years earlier, precise specifications were issued in the call for tenders. Four companies—Sperry Gyroscope Ottawa Ltd with its Mark Time meter, the Duncan Parking Meter Company of Montreal with its Duncan “50” and Duncan “60” models, The Red Ball Parking Meter Company of Toronto, and the Park-o-Meter Company also of Toronto—submitted bids to install 925 meters. Nettleton Jewellers examined the clockwork mechanism of all test machines submitted with the tenders. The winner was the Duncan Parking Meter Company of Montreal for its economy Duncan “50” model at $55 each.

Within weeks of the tender being accepted in February 1958, meter poles began to sprout on Ottawa streets. After testing, the first meters went “live” on Rideau Street on Friday, 25 April 1958. Traffic Inspector Callahan said that the meters were effective immediately and “must be fed” wherever they had been installed. Motorists were also given instruction on how to park—with front wheels opposite the machines. If a car occupied more than one space, both meters would have to be fed, five cents for 30 minutes, 10 cents for an hour. It was also illegal for motorists to stay longer than one hour; topping up the meter was not permitted. A parking infraction led to a $2 ticket. The meters were a great success, especially financially. The meters began pulling in $3,500 per week, considerably more than had been expected, with annual maintenance and collection expenses placed at only $20,000.

Over the next half century, the ubiquitous parking meter ruled downtown curbsides, standing every car length or two depending on whether single-headed or double-headed machines were being used. But in the 2000s, single-space curbside meters began to give way in Ottawa to multi-space machines (Pay and Display) that gave motorists a slip of paper that indicated the expiry time to be placed on the dashboard. This innovation permitted more cars to be parked on a given street, and eliminated “free” parking when a motorist parked in a spot with unused time on a standard meter. It also helped to reduce the clutter of unsightly meters on city sidewalks.

Other technological advances are also reducing the number of parking meters. Some communities have adopted in-vehicle parking meters—an electronic device that motorists can charged up and display on a car window. Others have embraced pay-by-phone parking with licence plate enforcement. In 2012, pay by telephone parking arrived in Ottawa through a system called “PaybyPhone” that is available in major cities around the world. After registering, a motorist enters a location number and selects the desired length of parking time up the permitted maximum. The parking charge is automatically debited to a credit card. Parking enforcement officers have a hand-held device that has real-time access to licence plate numbers and paid vehicles.

Looking forward, one can envisage further technological changes that could accelerate the demise of the parking meter, including in-car sensors and shared, autonomous vehicles that people call when needed. The parking meter, even the modern, multi-space machines now found on Ottawa streets, may soon become as rare as a telephone call box.

Sources:

Everett, Diana, 2009. “Parking Meter,” Oklahoma Historical Society.

Google Patents, 2017. Coin Controlled Parking Meter, US2118318 A, Inventor: Carl c Magee, May 24, 1938.

Grush, Ben, 2014, “Smart Attrition: As the parking meter follows the pay phone,” Canadian Parking Associatio.

Ottawa, (City of), 2017. How to pay for parking, http://ottawa.ca/en/residents/transportation-and-parking/parking/how-pay-parking.

Ottawa Sun, 2012. “Pay by phone parking arrives,” 5 April.

Ottawa Citizen, 1958. “Something Has Been Added,” 19 April.

Ottawa Journal, 1935. “The Automat of the Curbstone,” 29 July.

——————-, 1936. “Parkometer Proposal Is Referred To Board,” 22 September.

——————-, 1936. “Parking By Meter,” 23 September.

——————-, 1936. “Consider Parkometer Plan,” 23 September.

——————-, 1938. “No Harm In Trying The Parking Meters,” 16 April.

——————-, 1938. “Council Rejects Parking Meter Plan,” 21 June.

——————-, 1948. “Ottawa Firm Seeks Injunction to Restrain Meter Negotiations,” 10 June.

——————-, 1948. ‘“In Again, Out Again Meters’ Voted Out at Council Caucus,” 12 June.

——————-, 1948. “Right Decision on Parking Meters.” 19 June.

——————-, 1948. “And Now Let’s Forget Them!” 23 June.

——————-, 1950. “Parking Meters Approved For Eastview,” 26 October.

——————-, 1951. “134 Parking Meters Go In At Eastview,” 7 May.

——————-, 1951. “Eastview Find Parking meters Clear Montreal Road,” 16 June.

——————-, 1953. “Down With Meters Says Mayor,” 23 December.

——————-, 1957. “Board of Control,” 13 December.

——————-, 1957. “Parking Meters,” 17 December.

——————-, 1958. “Six companies Tender On Meters,” 29 January.

——————-, Parking Meter Proposal Submitted,” 31 January.

——————-, 1958. “Ottawa Buys 1,000 Parking Meters,” 18 February.

——————-, 1958. “Rideau Street Parking Meters In Operation,” 25 April.

——————-, 1958. “Meters Earn $3,500 A Week,” 14 August.

PaybyPhone, 2017. Welcome to PaybyPhone, Ottawa.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Nabu Network

26 October 1983

By the early 1980s, Ottawa was a hot-bed of high tech activity. Surrounding established companies, such as Bell Northern Research and Mitel, a cluster of small, ambitious telecommunications and computer-related firms with exotic names had emerged. These included Gandalf Data, Norpak, Xicom, and Orcatech, to name but a few. Many fizzed for a while, only to quickly disappear due to competition, rapidly changing technology, weak consumer demand, and inadequate funding. One that for a time stood out from the pack was NABU. Named for the Babylonian god of wisdom and writing, NABU was an acronym for “Natural Access to Bidirectional Utilities.” In its initial incarnation, the start-up was formally known as NABU Manufacturing Corporation. It was listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange in December 1982, raising $26 million in its initial public offering. The Ottawa-area company was itself the product of a number of mergers and acquisitions, including Bruce Instruments of Almonte, a manufacturer of remote television converters, Computer Innovations, a seller of computer hardware and software, Mobius Software, Andicon Technical Products of Toronto, a producer of small business computers, Volker-Craig of Kitchener, a manufacturer of video-display terminals, and Consolidated Computer Inc.(CCI), a relatively large, but troubled, government-owned, Canadian computer manufacturer and distributor. NABU bought CCI for one dollar from the federal government after the company had burned through $118 million of taxpayers’ money.

With close to 900 employees, half of whom were based in the Ottawa area, NABU had a multi-faceted business strategy. First, it planned to take on the business market, selling desk-top computers for word processing and data management. Initially producing the NABU 1100 in its Almonte plant, it released the 16-bit NABU 1600 in 1983. The 1600 version had 256 kilobytes of random-access memory (RAM), expandable to 512K, and a 10-megabyte hard drive, and used Intel’s 8086 processor. (Today’s laptop computers have eight to sixteen gigabytes of RAM, with up to 4 terabytes of hard drive, though with cloud computing, the sky is the limit for data storage.) It also came with a high density mini-floppy disk drive with storage for 800K of formatted data. Three people could use the NABU computer simultaneously doing different tasks. The price for the NABU 1600 was a breathtaking $9,800, equivalent to more than $21,000 in today’s money.

Second, NABU aimed to produce the first Canadian microcomputer for home use, taking on the likes of Commodore, IBM, Xerox, and a fledgling company that had gone public in December 1980 called Apple Computer. Third, the company envisaged selling on-line services to households. After buying or renting a NABU home microcomputer, and using its television as a monitor, a familiy could access programmes and data stored in NABU’s central server (a DEC mainframe) through a cable company’s broadband network. As the transmission of television signals only used a portion of the information-carrying capacity of cable networks, there was ample space for the transmission of other data-carrying services without degrading the television signals. The speed that the data could be transmitted on the coaxial cables employed by the cable companies (6.5 megabits per second) was also hundreds of times faster than what could be achieved over telephone lines.

By joining what was advertised as the NABU Network, cable company subscribers who bought the NABU package of services would have access to a wide range of educational and financial programmes, video games, news, weather, sports, and financial data including stock market quotations. In addition to consulting the Ottawa Citizen’s “Dining Out” guide, subscribers could read their daily horoscope, learn to type, balance household budgets, and improve their maths skills. A number of video games were also developed specifically for NABU with the help of another talented Ottawa firm, Atkinson Film Arts, featuring the comic strip characters, the Wizard of Id and B.C. In one game, called The Spook, billed to be superior to the popular arcade game Pac-Man, a player could guide a character through the dungeons of the kingdom of Id to freedom. Subscribers also had access to the space games Demotrons and Astrolander, a tennis game, and a downhill skiing game.

An even more outstanding feature of the NABU Network was two-way communication made possible by Telidon, a videotext/teletext service developed by the Canadian Communications Research Centre. NABU envisaged subscribers doing their banking and shopping from the comfort of their home. Also possible were electronic mail and remote data storage—an early form of cloud computing. In essence, NABU had foreshadowed today’s wired world, a decade before the launch of the Internet.

After rolling out their home computers at the end of May 1983, NABU launched its Network services in Ottawa on 26 October 1983. Initially, the service was only available to Ottawa Cablevision subscribers, i.e. people who resided west of Bank Street. One could purchase the NABU home computer for $950, or rent the unit for $19.95 per month, plus an addition $9.95 for NABU’s “lifestyle software.” For this price, one received the NABU 80K personal computer, a cable adaptor, a keyboard, a games controller, and thirty lifestyle games and programmes; the inventory of games and programmes later rose to roughly one hundred. For an extra $4.95 per month, subscribers had access to LOGO, an educational-based programming language, and LOGO-based programmes. NABU executives hoped to receive orders from at least five per cent of Ottawa Cablevision’s 90,000 customers within six months. In early 1984, the service was made available to subscribers of Skyline Cablevision, i.e. people who resided east of Bank Street. The plan was to introduce the NABU Network to forty cities across North American by the end of 1985. NABU’s first foray into the U.S. market took place in Alexandria, Virginia, close to Washington D.C., in the spring of 1984. To lead the U.S. charge, NABU hired Thomas Wheeler, former president of the US National Cable Television Association.

Unfortunately, things did not go as planned. When NABU’s line of business computers failed to meet expectations, the company hunkered down to focus on its more promising NABU Network. A corporate restructuring at the end of October 1983 led to the NABU Manufacturing Corporation being split into two companies, the NABU Network Corporation and Computer Innovations. The latter company quickly disappeared into oblivion. NABU Network struggled on for a time. By late 1984, it had about 1,500 customers in the Ottawa region, and a further 700 in Alexandria. This was not enough to make the enterprise viable. With the home computer market seen as being too competitive, the company de-emphasized its proprietary hardware to focus on the delivery of its software. In in a last ditch effort to attract subscribers, adaptors were offered so that owners of Commodore and other home computers could access the NABU Network.

It was not enough. In November 1984, the Campeau Corporation, NABU’s principal shareholder and largest creditor, pulled the plug on the failing enterprise. Having already invested more than $25 million, and, with little indication that NABU could attract sufficient subscribers to break even, let alone turn a profit, Campeau was unwilling to pour more money into the venture. NABU’s remaining 200 employees were laid off. John Kelly resigned as CEO and chairman of the NABU Network Corporation. Trading in NABU Network shares were suspended, with the company delisted from the Toronto Stock Exchange in January 1985. When it finally provided financial statements as of September 1984, the company had assets of only $4 million, with liabilities of $30 million. NABU shares, which were sold for $12.75 each at the company’s IPO two years earlier, were worthless.

Still confident about the concept of linking home computers to a central server using cable networks, Kelly formed a new, private company called the NABU Network (1984) to continue providing programmes and video games under licence to NABU subscribers in Ottawa; the U.S. service in Alexandria was discontinued. The new successor company hired back roughly 30 of the staff previously laid off. Subscriptions were sold door-to-door by Amway. Forever the optimist, Kelly hoped to have 6,000-8,000 subscribers by the summer of 1986. It was not to be. Limping along for eighteen months, the company ceased operations at the end of August 1986. The NABU Network dream was no more.

Why did NABU Network fail? In 1986, Kelly attributed its failure to the network concept being “ahead of its time,” and a slump in the home computer industry that killed the NABU personal computer. Part of the problem was that home computers themselves were not widely accepted; relatively few homes had them in the mid-80s. Many saw them as expensive toys rather than an indispensable part of everyday life. Content on the NABU Network was also an issue. Thomas Wheeler, who headed the company’s U.S. operations, and who is currently the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) in the United States, attributed the company’s failure to its dependence on cable company operators for its subscribers. In contrast, America Online (AOL) in the United States, which launched a similar, but far inferior, dial-up service in 1989, was wildly successful, at least for a time. Wheeler credits AOL’s success to it being available to anyone with a telephone and a modem. Ironically, cable companies later became important internet service providers.

In 2005, the York University Computer Museum began a programme to reconstruct the NABU Network, and develop an on-line collection documenting the NABU technology. It called the NABU Network “a technologically and culturally significant achievement.” Four years later, the Museum’s version of the NABU network was officially demonstrated. There for the event was John Kelly, NABU’s president and chief executive officer.

Sources:

IEEE Canada, 200? (Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers), The Internet Before Its Time: NABU Network in the Nation’s Capital.

McCracken, Harry, 2010. “A History of AOL, as Told in its Own Old Press Releases,” Technologizer, 24 May.

Montreal Gazette (The), 1983. “Nabu banking on its ‘network.’” 18 November.

———————–, 1985. “Amway to sell Nabu software,” 29 January.

———————–, 1985. “Nabu files statement,” 1 March.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1982. “Nabu goal: To make first Canadian microcomputers,” 23 March.

——————-, 1982. “Nabu adds videogames to service, 31 May.

——————-, 1982. “Nabu teaches computer ‘albatross” how to fly again,” 8 December.

——————-, 1983. “Nabu 1600 hits market across U.S., 27 May.

——————-, 1983. “Nabu 16-Bit Micro Features Intel 8086, 8087 Co-Processors,” 26 October.

——————-, 1983. “World’s first cable-TV computer on line,” 26 October.

——————-, 1983. “The Magic of The Nabu Network, 28 October.

——————-, 1984. “Skyline cable custmoers to get Nabu Network,” 25 April.

——————-, 1984. “Nabu Network reports $2.5 million loss,” 29 May.

——————-, 1984. “Role of Nabu’s own computer played down,” 19 June.

——————-, 1984. “Nabu proving technology before any expansion,” 19 June.

——————-, 1984. “Nabu chief forms new company,” 23 November.

——————-, 1985. “Trading stopped on Nabu shares by Ontario Securities Commission,” 24 January.

——————-, 1986. “Plug finally pulled on failing Nabu Network,” 19 July.

Reyes, Julian, 2014. “How Tom Wheeler Almost Invested The Internet,” Fusion, 27 May.

Wheeler, Tom, 2015, “This is how we will ensure net neutrality,” Wired, 4 February.

York University, 2009. NABU Network Reconstruction Project at YUCoM, (York University Computer Museum).

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Water Woes

23 August 1912

Pure, sparkling clean, tap water. We tend to take it for granted. Occasionally our complacency is shaken, as it was in 2000 when seven people died in Walkerton, Ontario when e. coli contaminated the town’s drinking water. But, thankfully, that was a rare event. Ottawa’s tap water consistently gets top grades for quality. Raw water from the Ottawa River is filtered and chemically treated in several steps to remove bacteria, viruses, algae, and suspended particles. More than 100,000 tests are conducted each year to ensure that crystal clear, odourless, and, above all, safe water is supplied to Ottawa’s households and businesses.

But this was not always the case. One hundred years ago, two old, poorly maintained intake pipes that drew untreated water from mid-river were the source of the city’s water supply. But the Ottawa River was dangerously polluted. The region’s many lumber mills routinely dumped tons of waste each year into the river. Decomposing sawdust was actually responsible for the death of a man from Montebello in 1897 when he was thrown from his boat by a methane explosion. Meanwhile, raw sewage from Ottawa’s burgeoning population, as well as from Hull and other riverside communities, was simply flushed into the river. Sewage from inadequately maintained outdoor privies also leaked into the region’s many creeks and streams that fed the Ottawa River. It was a recipe for typhoid fever.

While typhoid stalked all major Canadian cities during the first years of the twentieth century, Ottawa was among the worst affected. The disease annually claimed on average twenty lives, a shockingly high number for a community of perhaps 75,000 souls. Most of the deaths were recorded in the poor, squalid districts of Lower Town and LeBreton Flats. Civic officials, at best complaisant, at worse criminally negligent, did nothing. It was perhaps easier, and cheaper, to blame the poor’s unhygienic living conditions than to do something about the water supply. But even the death in 1907 of the eldest daughter of Lord Grey, the Governor General, who had been visiting her parents from London, didn’t prompt action.

Ignorance wasn’t a viable defence for civic leaders’ lack of action. By 1900, health officials were very familiar with Samonella enterica typhi, the bacteria that caused typhoid, and how to combat it. They were fully aware that the most common form of transmission was drinking water polluted by human sewage. They also knew that chlorine could be used as a disinfectant, rendering the water safe for consumption. Typhoid was a fully preventable disease.

In 1910, an American expert was finally called in to look at ways of improving Ottawa’s water supply. He recommended the immediate addition of hypochlorite of lime, a bactericide, as an interim remedy until a mechanical filtration plant could be constructed. Alternatively, he proposed that cleaner, albeit much more expensive, water be piped in from Lake McGregor in the Gatineau Hills. His report was shelved.

Disaster struck in early January 1911. In the space of weeks, there were hundreds of typhoid cases in the city. By the end of March, sixty people had died. By year-end, the death toll had reached eighty seven. Even before the epidemic had run its course, the first investigation by the chief medical health officer of Ontario concluded that it was due to contaminated city water. Owing to low pressure, an emergency intake valve in Nepean Bay had been opened to raise water pressure in case of fire. The intake had sucked in raw sewage into the water mains. The source of pollution was traced to Cave Creek (now a sewer) that ran through Hintonburg, a heavily populated area which relied on outdoor privies that emptied into the creek. Blame for the epidemic was placed squarely on civic officials who had done nothing to ensure a safe water supply for Ottawa citizens. A second study concluded that had hypochlorite of lime been added to the city’s water as recommended in the 1910 study, the outbreak could have been averted.

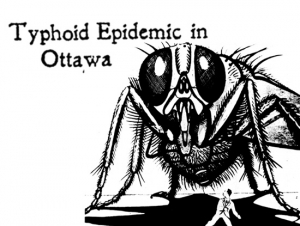

Ottawa press statement falsely indicating the end of the 1912 typhoid epidemic

Ottawa press statement falsely indicating the end of the 1912 typhoid epidemic

The Toronto World, 24 August 1912Some modest steps were taken to address the situation. Hypochlorite of lime was finally added to the water, but various technical problems prevented the full amount of the chemical from being used. A new intake pipe was also put down in 1911 and was in use by the following April. But the water remained contaminated as a significant portion of the city’s water continued to be sourced through the old, leaky intake pipes. Although Ottawa’s engineer warned city officials that the water supply remained in a dangerous condition, nothing further was done.

In June 1912, typhoid returned to Ottawa with a vengeance. So bad were conditions that MPs were reluctant to return to Ottawa for the autumn1912 parliamentary session, and lobbied for Parliament to be shifted at least temporarily to Toronto, or even Winnipeg. More radical voices wanted Canada’s capital to be moved permanently if Ottawa could not provide government workers with clean water. The Toronto World thundered that the city was advertising itself “from Vancouver to Halifax as a pest hole of diseases.”

With the disease striking during the prime tourist season, civic and business leaders were keen to play down the extent of the problem and the underlying causes. In mid-August, a secret meeting was held between business leaders, Mayor Charles Hopewell and the city’s medical officer of health to discuss the impact of the epidemic on commerce. On 23 August, the medical officer of health announced that the “typhoid epidemic had run its course” and that the water was now safe to drink; bacteriological tests for the previous five weeks having showed “conclusively” that the water was free from contaminants and was “fit for consumption without boiling or otherwise treating it.” It was a barefaced lie. Cases of typhoid continued to occur. Tragically, there were twelve additional deaths in September and a further nineteen in October, weeks after the epidemic had supposedly ended. In total, roughly 1,400 cases of typhoid were recorded in 1912 with 98 fatalities. In November 1912, City Council self-servingly declared that it was “not legally responsible to the [typhoid] sufferers, but only morally so.” It voted a mere $3,000 to cover urgent relief needs.

This time a judicial inquiry was held into the two epidemics. An investigation by provincial authorities indicated continued gross contamination of the water notwithstanding what the medical officer of health had said. It was also shown that contamination occurred due to leaks in both old and new pipes. The city engineer was suspended and Ottawa’s medical officer of health resigned. Although there was insufficient evidence to indict Mayor Hopewell, his reputation was ruined. He declined to run again as mayor in the 1912 election. In 1914, the provincial board of health concluded that “after careful investigations” the outbreaks of typhoid fever were “caused by the use of sewage-polluted water from the Ottawa River.” It added that it was “a disgraceful fact that up to the present date no satisfactory plan for a pure supply for that city has been adopted.”

While repairs were made to the intake pipes and the water was treated with ammonia and chlorine, it was only a temporary fix to Ottawa’s water woes. A permanent solution had to wait almost twenty years as debate raged on city council and in the courts between those that supported the purification of Ottawa River water and the “Lakers” who wanted to pipe in clean water from 31-Mile Lake or Lake Pemichangan north of the city in the Gatineau Hills. Construction on the Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant finally began in 1928. When the plant opened three years later, Ottawa finally had safe tap water.

Sources:

Bourque, André, 2013. City of Ottawa Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant (82 Years Young and Going Strong), Atlantic Canada Water & Wastewater Association.

City of Ottawa, 2014. Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant.

H2O Urban, 2008. Ottawa Report, 22 November.

Jacangelo, Joseph G. and Trussell, R. Rhodes, 2009. “International Report: Water and Wastewater Disinfection: Trends, Issues and Practices,.

Lloyd, Sheila, 1979. “The Ottawa Typhoid Epidemics of 1911 and 1912: A Case Study of Disease as a Catalyst for Urban Reform,” Urban History Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, p. 66-89.

Murray, Mathew, 2012. Dealing with Wastewater and Water Purification from the Age of Early Modernity to the Present: An Inquiry Into the Management of the Ottawa River, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, University of Ottawa.

Ottawa Riverkeeper, 2007. Notes on a Water Quality and Pollution History of the Ottawa River.

Provincial Board of Health, 1914. 1913 Annual Report.

The Citizen, 1912. “City’s Responsible for Typhoid Claims,” 12 November.

—————–, 1913. “Harsh Condemnation of Ottawa’s Civic Government by Members of Commons in Discussing Pollution of Streams Bill,” 26 April.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1953. “History of Ottawa’s Water System Long and Bloody One,” 28 April.

The Evening Telegram, 1907. “Earl Grey’s Daughter Dead,” 4 February.

The Toronto World, 1912. “M.P.’s Afraid To Go To Ottawa,” 5 August.

——————-, 1912, “Typhoid Epidemic in Ottawa Nearly Over,” 24 August.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.