23 August 1912

Pure, sparkling clean, tap water. We tend to take it for granted. Occasionally our complacency is shaken, as it was in 2000 when seven people died in Walkerton, Ontario when e. coli contaminated the town’s drinking water. But, thankfully, that was a rare event. Ottawa’s tap water consistently gets top grades for quality. Raw water from the Ottawa River is filtered and chemically treated in several steps to remove bacteria, viruses, algae, and suspended particles. More than 100,000 tests are conducted each year to ensure that crystal clear, odourless, and, above all, safe water is supplied to Ottawa’s households and businesses.

But this was not always the case. One hundred years ago, two old, poorly maintained intake pipes that drew untreated water from mid-river were the source of the city’s water supply. But the Ottawa River was dangerously polluted. The region’s many lumber mills routinely dumped tons of waste each year into the river. Decomposing sawdust was actually responsible for the death of a man from Montebello in 1897 when he was thrown from his boat by a methane explosion. Meanwhile, raw sewage from Ottawa’s burgeoning population, as well as from Hull and other riverside communities, was simply flushed into the river. Sewage from inadequately maintained outdoor privies also leaked into the region’s many creeks and streams that fed the Ottawa River. It was a recipe for typhoid fever.

While typhoid stalked all major Canadian cities during the first years of the twentieth century, Ottawa was among the worst affected. The disease annually claimed on average twenty lives, a shockingly high number for a community of perhaps 75,000 souls. Most of the deaths were recorded in the poor, squalid districts of Lower Town and LeBreton Flats. Civic officials, at best complaisant, at worse criminally negligent, did nothing. It was perhaps easier, and cheaper, to blame the poor’s unhygienic living conditions than to do something about the water supply. But even the death in 1907 of the eldest daughter of Lord Grey, the Governor General, who had been visiting her parents from London, didn’t prompt action.

Ignorance wasn’t a viable defence for civic leaders’ lack of action. By 1900, health officials were very familiar with Samonella enterica typhi, the bacteria that caused typhoid, and how to combat it. They were fully aware that the most common form of transmission was drinking water polluted by human sewage. They also knew that chlorine could be used as a disinfectant, rendering the water safe for consumption. Typhoid was a fully preventable disease.

In 1910, an American expert was finally called in to look at ways of improving Ottawa’s water supply. He recommended the immediate addition of hypochlorite of lime, a bactericide, as an interim remedy until a mechanical filtration plant could be constructed. Alternatively, he proposed that cleaner, albeit much more expensive, water be piped in from Lake McGregor in the Gatineau Hills. His report was shelved.

Disaster struck in early January 1911. In the space of weeks, there were hundreds of typhoid cases in the city. By the end of March, sixty people had died. By year-end, the death toll had reached eighty seven. Even before the epidemic had run its course, the first investigation by the chief medical health officer of Ontario concluded that it was due to contaminated city water. Owing to low pressure, an emergency intake valve in Nepean Bay had been opened to raise water pressure in case of fire. The intake had sucked in raw sewage into the water mains. The source of pollution was traced to Cave Creek (now a sewer) that ran through Hintonburg, a heavily populated area which relied on outdoor privies that emptied into the creek. Blame for the epidemic was placed squarely on civic officials who had done nothing to ensure a safe water supply for Ottawa citizens. A second study concluded that had hypochlorite of lime been added to the city’s water as recommended in the 1910 study, the outbreak could have been averted.

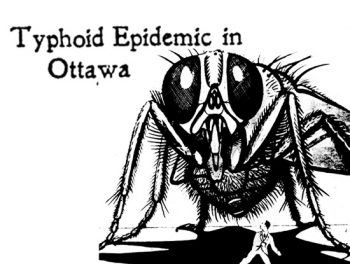

Ottawa press statement falsely indicating the end of the 1912 typhoid epidemic

Ottawa press statement falsely indicating the end of the 1912 typhoid epidemic

The Toronto World, 24 August 1912Some modest steps were taken to address the situation. Hypochlorite of lime was finally added to the water, but various technical problems prevented the full amount of the chemical from being used. A new intake pipe was also put down in 1911 and was in use by the following April. But the water remained contaminated as a significant portion of the city’s water continued to be sourced through the old, leaky intake pipes. Although Ottawa’s engineer warned city officials that the water supply remained in a dangerous condition, nothing further was done.

In June 1912, typhoid returned to Ottawa with a vengeance. So bad were conditions that MPs were reluctant to return to Ottawa for the autumn1912 parliamentary session, and lobbied for Parliament to be shifted at least temporarily to Toronto, or even Winnipeg. More radical voices wanted Canada’s capital to be moved permanently if Ottawa could not provide government workers with clean water. The Toronto World thundered that the city was advertising itself “from Vancouver to Halifax as a pest hole of diseases.”

With the disease striking during the prime tourist season, civic and business leaders were keen to play down the extent of the problem and the underlying causes. In mid-August, a secret meeting was held between business leaders, Mayor Charles Hopewell and the city’s medical officer of health to discuss the impact of the epidemic on commerce. On 23 August, the medical officer of health announced that the “typhoid epidemic had run its course” and that the water was now safe to drink; bacteriological tests for the previous five weeks having showed “conclusively” that the water was free from contaminants and was “fit for consumption without boiling or otherwise treating it.” It was a barefaced lie. Cases of typhoid continued to occur. Tragically, there were twelve additional deaths in September and a further nineteen in October, weeks after the epidemic had supposedly ended. In total, roughly 1,400 cases of typhoid were recorded in 1912 with 98 fatalities. In November 1912, City Council self-servingly declared that it was “not legally responsible to the [typhoid] sufferers, but only morally so.” It voted a mere $3,000 to cover urgent relief needs.

This time a judicial inquiry was held into the two epidemics. An investigation by provincial authorities indicated continued gross contamination of the water notwithstanding what the medical officer of health had said. It was also shown that contamination occurred due to leaks in both old and new pipes. The city engineer was suspended and Ottawa’s medical officer of health resigned. Although there was insufficient evidence to indict Mayor Hopewell, his reputation was ruined. He declined to run again as mayor in the 1912 election. In 1914, the provincial board of health concluded that “after careful investigations” the outbreaks of typhoid fever were “caused by the use of sewage-polluted water from the Ottawa River.” It added that it was “a disgraceful fact that up to the present date no satisfactory plan for a pure supply for that city has been adopted.”

While repairs were made to the intake pipes and the water was treated with ammonia and chlorine, it was only a temporary fix to Ottawa’s water woes. A permanent solution had to wait almost twenty years as debate raged on city council and in the courts between those that supported the purification of Ottawa River water and the “Lakers” who wanted to pipe in clean water from 31-Mile Lake or Lake Pemichangan north of the city in the Gatineau Hills. Construction on the Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant finally began in 1928. When the plant opened three years later, Ottawa finally had safe tap water.

Sources:

Bourque, André, 2013. City of Ottawa Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant (82 Years Young and Going Strong), Atlantic Canada Water & Wastewater Association.

City of Ottawa, 2014. Lemieux Island Water Purification Plant.

H2O Urban, 2008. Ottawa Report, 22 November.

Jacangelo, Joseph G. and Trussell, R. Rhodes, 2009. “International Report: Water and Wastewater Disinfection: Trends, Issues and Practices,.

Lloyd, Sheila, 1979. “The Ottawa Typhoid Epidemics of 1911 and 1912: A Case Study of Disease as a Catalyst for Urban Reform,” Urban History Review, Vol. 8, No. 1, p. 66-89.

Murray, Mathew, 2012. Dealing with Wastewater and Water Purification from the Age of Early Modernity to the Present: An Inquiry Into the Management of the Ottawa River, Department of Anthropology and Sociology, University of Ottawa.

Ottawa Riverkeeper, 2007. Notes on a Water Quality and Pollution History of the Ottawa River.

Provincial Board of Health, 1914. 1913 Annual Report.

The Citizen, 1912. “City’s Responsible for Typhoid Claims,” 12 November.

—————–, 1913. “Harsh Condemnation of Ottawa’s Civic Government by Members of Commons in Discussing Pollution of Streams Bill,” 26 April.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1953. “History of Ottawa’s Water System Long and Bloody One,” 28 April.

The Evening Telegram, 1907. “Earl Grey’s Daughter Dead,” 4 February.

The Toronto World, 1912. “M.P.’s Afraid To Go To Ottawa,” 5 August.

——————-, 1912, “Typhoid Epidemic in Ottawa Nearly Over,” 24 August.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.