Super User

Sex and Security

4 March 1966

It would be hard to find a better demonstration of the adage that people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones than the Gerda Munsinger case, a scandal that burst without warning onto the Ottawa political scene in early 1966. On 4 March, Lucien Cardin, the Justice Minister in Lester B. Pearson’s Liberal minority government, came under a blistering, personal attack by John G. Diefenbaker, the Progressive Conservative leader of the opposition. The object of Diefenbaker’s ire was the government’s handling of George Victor Spencer, a Vancouver postal clerk who had been fired from his job for selling information to the Russians. Two Soviet diplomats were expelled from Canada in the case. Spencer had provided names of dead people, bankrupt companies, and closed schools, which would have been useful in creating background cover stories for Russian agents based in the lower mainland area, as well as information about post office security. There was also evidence that the Russians were grooming Spencer to act as a “letter box” for passing on messages. In return, Spencer was paid several thousand dollars to meet with his Soviet handlers in Ottawa. He had also hoped to get a free ticket to visit Russia.

On that fateful March afternoon, Cardin was defending his department’s decision not to press criminal charges against Spencer. The opposition, sensing blood, demanded a formal inquiry to examine possible weaknesses in Canada’s security system, and to give Spencer, who had been fired without the right of appeal, an opportunity of a hearing. Cardin refused. Baited by Diefenbaker, Cardin lashed out saying that Diefenbaker was “the last person in the house to give advice on the handling of security cases in Canada.” He then added “I want the right hon. gentleman to tell the house about his participation in the Monseignor (sic) case when he was prime minister of this country.” His words caught people’s attention.

Prime Minister Pearson, who was in a weak political position, caved in to demands for an inquiry into the Spencer case. Overruled by Pearson, Cardin tendered his resignation from cabinet. But he almost immediately backtracked after receiving encouragement to stay on from his cabinet colleagues and the Quebec caucus of the Liberal Party. With rumours swirling in Ottawa about Cardin’s future, and a new security scandal, Cardin called a press conference where he acknowledged his aborted resignation over the Spencer file. He also reiterated what he said in the House of Commons, and provided startling new details. This time he got the name right. He claimed that a former Soviet spy named Gerda Munsinger had been involved with two or more Conservative Cabinet ministers during the Diefenbaker years. He claimed that the affair was worse that the Profumo case in Britain. (In 1961, John Profumo, the Secretary of State for War, resigned his cabinet position and his parliamentary seat after admitting to having had an affair with a young woman, Christine Keeler, who allegedly was also sleeping with the Soviet naval attaché in London.) Cardin also claimed that Diefenbaker and David Fulton, who was Justice Minister at the time, had known that cabinet ministers were involved with Munsinger, but did nothing, despite the evident security risks. He added that he believed Munsinger had died of leukemia.

Gerda Munsinger, circa 1966, the "Mata Hari" of the Cold WarCardin’s sensational allegations rocked the House of Commons. Normal business came to abrupt halt. Outraged Conservative MPs demanded that Cardin reveal the names of the former ministers, or resign. In turn, Prime Minister Pearson announced a judicial inquiry into the affair, and challenged the opposition to defeat his government.

Gerda Munsinger, circa 1966, the "Mata Hari" of the Cold WarCardin’s sensational allegations rocked the House of Commons. Normal business came to abrupt halt. Outraged Conservative MPs demanded that Cardin reveal the names of the former ministers, or resign. In turn, Prime Minister Pearson announced a judicial inquiry into the affair, and challenged the opposition to defeat his government.

Toronto Star journalist Robert Reguly tracked down a very much alive Gerda Munsinger in Munich, Germany, and got an exclusive interview with her. She readily admitted her involvement with Conservative cabinet ministers. Quickly, details of Munsinger’s life, and who she had been dating, were circulating in the press.

She was born Gerda Heseler in Königsberg, East Prussia in 1929, which became Kaliningrad, after the war when the Soviet Union expelled its German inhabitants, and annexed the city. In 1952, she married Michael Munsinger, a U.S. serviceman stationed in Germany. But when the couple subsequently tried to move to the United States, Gerda Munsinger was denied entry on security grounds; she had a record of petty theft and prostitution in West Germany. As well, she had apparently admitted to having had a relationship with a Soviet KGB agent, and of having worked as a low-level Soviet spy. Their marriage was annulled. Later in 1952, Gerda Munsinger tried to immigrate to Canada under her maiden name, but was rejected on security grounds. She tried again in 1955, using her married name. This time, she was successful. Settling in Montreal, the aspiring model worked in various nightclubs connected with Montreal mobsters as a cashier or hostess. Allegedly, she was also a sometime prostitute.

In August 1959, she was introduced to Pierre Sévigny, the Associate Minister for Defence in Diefenbaker’s Conservative government. Sévigny was a much decorated veteran of World War II, who had lost a leg at the battle of the Rhineland. Their relationship became intimate. She was also introduced to George Hees, Minister for Trade and Commerce, and dined with him on several occasions. In late 1960, Munsinger applied with Sévigny’s help for a Canadian passport. Through their passport vetting process, the RCMP discovered that she had been denied entry into Canada eight years earlier. After placing Munsinger under surveillance, which included a wiretap, they discovered she was Sévigny’s “mistress.” The RCMP briefed David Fulton who informed the prime minister. Diefenbaker told Sévigny to break off the relationship. This he did, a decision made easier by Munsinger’s decision to return to Germany in early 1961. No further action was taken. Sévigny remained in his cabinet post as Associate Minister for National Defence until his resignation in 1963. Diefenbaker and Fulton kept the RCMP file confidential; other members of the cabinet were not informed.

When Sévigny’s name was publicly linked to that of Munsinger, the former minister went on the offensive. Appearing on CBC television, flanked by his wife and daughter, Sévigny admitted to having met Gerda Munsinger at a party in August 1959, and afterwards seeing her a few times socially, but their relationship was “just that, a social one.” He said he never had any reason to think she was a foreign agent, and was convinced that she never presented a security risk. He called Cardin “a despicable, rotten, little politician.”

Within days, the two judicial inquiries, one into the Pearson government’s handling the of the Spencer case, the other into the Munsinger Affair, were in full swing. The former case was handled by Justice Dalton Wells, while the latter was conducted by Justice Wishart Spence. Justice Wells completed his report in late July 1966. He completely vindicated the Pearson government’s actions in the Spencer case. He contended that George Spencer had been treated with “forbearance and fairness” by the Pearson government. Justice Wells also supported the government’s decision not to prosecute; Spencer was fatally ill with lung cancer, and died days before the Wells Commission started its hearings.

Two months later, Justice Spence gave his report on the Munsinger affair. It was devastating. While there was no evidence to suggest that Munsinger had worked as a spy in Canada, Justice Spence tore into the previous Conservative government’s handling of the case. While commending Fulton for bringing the RCMP brief on Munsinger promptly to the prime minister’s attention, he faulted him for not initiating a full investigation into whether there had been a security breach. One of the issues not investigated was the arrest and release of Munsinger for bouncing cheques in Montreal shops immediately before her return to Germany. Reportedly, Montreal police had been subjected to political pressure to release Munsinger, and were told that, if charges were pressed, a prominent politician would be blackmailed.

Diefenbaker, who refused to testify at the inquiry, came out very badly. Justice Spence argued that Diefenbaker had relied solely on his personal assessment of Sévigny’s character to retain him in cabinet. Had he read the background documents that supported the RCMP brief, Spence said that Diefenbaker would have clearly seen that Sévigny “was not telling the whole truth.” Moreover, Sévigny’s relationship with Munsinger was known by persons “said to be of unsavory reputation,” and had Diefenbaker done a bit of research “the danger of blackmail and improper pressure would have been revealed as startling.” He also chastised the former prime minister for not bringing the issue to his cabinet for discussion, and especially for not informing Douglas Harkness, the senior cabinet minister for national defence, as well as George Hees, who knew Munsinger on a casual basis, of the RCMP investigation. He also argued that if Diefenbaker had, despite everything, wanted to retain Sévigny in cabinet, he should have moved him to a less sensitive portfolio.

Justice Spence concluded that Pierre Sévigny had understated the closeness and the extent of his relationship with Gerda Munsinger, both to Diefenbaker and to the inquiry. While it had been argued that Sévigny’s strength of character was such that he could not have been pressured or blackmailed, Spence noted that Sévigny had not exhibited “such sterling qualities” on the one instance of pressure—when Diefenbaker confronted him about Munsinger. In addition, despite vague denials, there was no question that he had “actively used his influence to try to obtain Canadian citizenship for Mrs Munsinger.”

Finally, Justice Spence stated that all the allegations made by Lucien Cardin at his March press conference were true. Importantly, there were indeed aspects of the case that were worse than the Profumo affair in Britain. There, the cabinet minister in question had resigned his position and had apologized to Parliament. Sévigny had done neither.

One thing that Justice Spence did not comment on was why the Pearson government had taken so long to initiate an inquiry. Pearson had been informed of the Munsinger case almost two years previously. Consequently, was Cardin’s revelation in the House on 4 March 1966 a slip of the tongue, made while under pressure, or was it something planned to divert attention away from a weak, minority government assailed on many fronts? Fulton called the Spence report “one man’s opinion,” while Diefenbaker called it “the shabby device of a political trial.”

Pierre Sévigny never apologized for his actions. He believed “the scandal was built up out of nothing” by senior people in the Liberal Party. He claimed that he was “framed,” and that the scandal was use to cover up greater misdeeds. He saw himself as “the victim.” He died in 2004.

Gerda Munsinger, the woman at the centre of the affair, remarried after the Spence inquiry. She died in 1998.

Sources:

CBC Digital Archives, 1966. “Pierre Sévigny lashes out,” 12 March, CBC Television.

—————————–, 1966, “Gerda Munsinger Found in Munich, CBC Television,13 March, http://www.cbc.ca/archives/categories/war-conflict/cold-war/politics-sex-and-gerda-munsinger/munsinger-found-in-munich.html.

—————————-, 1973. “Sévigny looks back at Munsinger affair,” 23 July. This Country in the Morning, CBC Radio.

English, John, 2005-15. “Pearson, Lester Bowles,” Dictionary of Canadian Biography.

House of Commons, 1966. Debates, 27th Parliament, Volumes 2 and 3. March.

The Gazette, “Cardin Retracts Resignation Bowing To Party Pressure,” Montreal, 10 March.

————–, 1966. “Tempest Blows Up In Parliament After MP-Spy Romance Charge,” Montreal, 11 March.

————–, 1966. “Government Fully Supported By Report On Spencer Case,” 27 July.

The Globe and Mail, 1966. “U.S. denied Gerda entry: ex-husband,” 14 March.

————————, 1966. “Gerda spied for Soviet, risked blackmail: RCMP,” 26 April.

————————, 1966. “‘Sevigny told less than the whole truth,’” 24 September.

————————, 1966. “Wretchedly served,” 24 September.

————————, 2011, “Reporter found Hal Banks, Gerda Munsinger,” 5 March.

The Sun, 1966. “Spencer ‘Russian Spy Tool,’” Vancouver, 5 May.

Images: Gerda Munsinger, circa 1966.

The Evening Journal - Woman's Edition

13 April 1895

Prior to the twentieth century, women in Canada, and indeed throughout most of the world, had few political, economic or social rights. Typically, women went directly from the jurisdiction of their fathers to that of their husbands. They had little control over property, income, children, or their own bodies. Women were denied the franchise, banned from most professions, and were often forbidden university-level education. A woman’s place in society was limited to caring for her husband, raising a family and managing the household. Few married women were in the paid labour force. If a single woman was forced by poverty to seek out paid employment, she was confined to occupations that were extensions of home life—carrying for children, sick, or elderly, or being a seamstress, or a house maid. Teaching was also acceptable. Once married, however, a woman was expected to resign her position so that she could devote her time to wifely duties. In 1901, only 14 per cent of Canadian women were in the paid labour force, many earning only a pittance, much less than their male counterparts doing the same work, a rationale being that a man had a family to support whereas a woman had only herself.

However, during the later decades of the nineteenth century, Canadian women began to organize and agitated for change. They challenged the widely-held belief that it was ordained by God that a woman’s place was in the home. They also rejected the paternalistic notion that they were the weaker sex, who must be sheltered from the hurly burly of politics, or worse did not have the intellectual capacity to work in the professions. But change came slowly in Canada, and when it did it came in small steps. In 1872, the Married Women’s Property Act gave married women the right to their own wages. Three years later, Dr Jennie Trout became the first woman to be licensed to practise medicine in Ontario. In 1876, Toronto women formed the Women’s Literary Society with a covert aim of obtaining equal rights; it later was transformed into the Toronto Women’s Suffrage Association. The Young Women’s Christian Association and the Women’s Christian Temperance Union were also formed during the 1870s, with a mission, among other things, to improve the lot of women. In 1884, Ontario granted married women the right to own and dispose of their own property without the consent of their husbands. In 1889, the Dominion Women’s Enfranchisement Association grouped local suffrage groups into a national body, giving them more political clout. In 1893, Lady Ishbel Aberdeen, the wife of the Governor General at that time and an early feminist, formed the National Council of Women in Canada to improve the status of women. The Council’s initial efforts focussed on women immigrants, factory workers and prisoners. In 1895, the Law Society of Upper Canada agreed to admit women as barristers.

Female suffrage was still a dream, however. In June 1895, the House of Commons debated votes for women…and thoroughly rejected such an outlandish idea. One Member of Parliament, Flavien Dupont, expressed the prevailing sentiment of the time. He argued against throwing “upon woman’s shoulders one of the heaviest burdens that bears on those of men, the burden of politics, the burden of electoral contests, the burdens of representation.” He contended “To invite the fair sex to take part in our political contests seems to me to be as humiliating and as shocking a proposition as to invite her to form part of our militia battalions.” Women over 21 years of age had to wait until 1917 to be enfranchised in Ontario, and until 1918 to be able to vote in federal elections.

Against this backdrop, the Ottawa Evening Journal ran a unique edition on Saturday, 13 April 1885—an all-women production of the newspaper. For that one day, Ottawa women assumed all the responsibilities, including managing, editing and reporting, necessary for producing a newspaper. The Editor for the day was Annie Howells Fréchette, a poet and the author of many magazine articles, some of which were published in Harper’s Magazine. She was the wife of the translator for the House of Commons. The Managing Editor was Mary McKay Scott, while the News Editor was Ellie Cronin. The Journal’s office boy was “the only person of the male persuasion” who assisted in the newspaper’s production. Female reporters selected and edited international stories that came in over the newswires, as well as covered local newsworthy events, including sports. Instead of a “Woman’s” column, a common feature in newspapers of the age, a “Gentleman’s” column appeared. Women also solicited advertisements from area businesses, and all letters to the Editor were written by women.

The Evening Journal - Woman's Edition, 13 April 1895This special edition of The Evening Journal was in support of the creation of a “Free” or Public Library in Ottawa. At that time, library resources in the Capital was essentially limited to the Parliamentary Library, the University of Ottawa library and the library of the Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society (OLSS). The OLSS, which had a small, circulating collection of roughly 3,100 volumes in 1895, was funded by Society members and an annual grant from the Ontario government. The Ottawa Council of Women, founded by Lady Aberdeen, together with women’s church groups and other charities, were the principal advocate of a free Ottawa Library that would be open to all. The special newspaper edition was a way of rallying support for the initiative. More tangibly, the profits from the issue would form the nucleus of a library fund. Library supporters hoped that others would contribute and, in time, lead to a grant from the City that would fund a Public Library.

The Evening Journal - Woman's Edition, 13 April 1895This special edition of The Evening Journal was in support of the creation of a “Free” or Public Library in Ottawa. At that time, library resources in the Capital was essentially limited to the Parliamentary Library, the University of Ottawa library and the library of the Ottawa Literary and Scientific Society (OLSS). The OLSS, which had a small, circulating collection of roughly 3,100 volumes in 1895, was funded by Society members and an annual grant from the Ontario government. The Ottawa Council of Women, founded by Lady Aberdeen, together with women’s church groups and other charities, were the principal advocate of a free Ottawa Library that would be open to all. The special newspaper edition was a way of rallying support for the initiative. More tangibly, the profits from the issue would form the nucleus of a library fund. Library supporters hoped that others would contribute and, in time, lead to a grant from the City that would fund a Public Library.

Given the purpose of the special, twenty-page, newspaper edition, there was an extensive front-page article making the case for a free, public library in Ottawa. Three principal motivations were outlined: a way of uplifting men and women to a higher plane; a means of securing greater remuneration for work; and a way to form better citizens, thereby adding to the advancement and stability of the state. A public library was viewed as an extension of the school system—a “peoples’ university where “rich and poor, old and young, may drink at its inexhaustible fountain.”

Besides articles in support of an Ottawa library, there was an array of fascinating news stories, both national and international, that emphasized women. One article titled La Penetenciaria featured a hard-hitting report on an Ottawa lady’s visit to a Mexican state prison in Guadalajara. Other story focussed on Canadian women in poetry. Front and centre was Emily Pauline Johnson, the daughter of a Mohawk hereditary chief and an English mother. Johnson’s poem “In Sunset” was published. Johnson is recognized today as one of Canada’s leading poets of the nineteenth century. Others profiled included Ethelwyn Wetherald, author and journalist at The Globe newspaper in Toronto, who wrote under the nom de plume Bel Thistlewaite, and Agnes Maule Machar. As well as being an early feminist, Machar wrote about Christianity and Darwinism, arguing that Christians should accept evolution as part of God’s divine plan.

Others stories had a more domestic focus. One provided tips on how to deal with servants: “If the mistress wishes her household machinery to run smoothly, give her orders for the day immediately after breakfast.” In turn, servants were advised never to “put white handled knives into hot water, and to “cleanse the sink with concentrated lye at least once a day.” In the light-hearted “Gentlemen’s Column,” “matters pertaining to the sterner sex” were dealt with, including “men’s rights, and, “the age when a man ceases to be attractive.” Regarding the former, the columnist thought that men looked after their own rights and the needs of their own sex far better than did women, “because they probably know more about them.” As for the latter issue, she thought that there was no definite conclusion.

Notable women in the Ottawa community also contributed articles to the special newspaper edition. Lady Aberdeen wrote a lengthy column about what “society girls” might do. She opined that “service is the solution of the problem of life.” In Experimental Farm Notes, Mrs William Saunders, the wife of the director of Ottawa’s Experimental Farm, described life on the Farm, and wrote about what the visitor could see in April, which included a “good display of early spring flowering bulbs.” Mrs Alexander, the Assistant Librarian at the Geological Museum, located at the Geological Survey at the corner of Sussex Avenue and George Street, wrote about the many treasures to be found there. In addition to an extensive collection of rocks and minerals, there were botanical, entomological exhibits as well as a collection of birds and mammals. A range of “Indian relics” were also on display from western Ontario, Yukon and the Queen Charlotte Islands, including a sacrificial stone of the Blackfoot Indians, also known as the Niitsitapi, presented to the Geological Survey by the Marquis of Lorne, a previous Governor General. The Geological Museum later became known as the Canadian Museum of Nature.

The most fascinating stories deal with women’s rights, providing a glimpse of the state of play at that time, and the aspirations of Canadian women in the late nineteenth century. There were at least two references to the decision just made by the Law Society of Upper Canada to admit women as barristers. One reporter with considerable foresight wrote:

Until two weeks ago, women in the province of Ontario had only the privilege of obeying or breaking the law. Now, however, they may assist men in interpreting it. And who can say that he is altogether wrong who looks forward to the time when they shall share in making it, either through the ballot box or the legislative assembles, or becoming its interpreters upon the bench?

In an article called “The Home,” Mrs Stone-Wiggins drew readers’ attention to the proverb “Women’s sphere is the home and of it she should be queen.” Notwithstanding the proverb’s wide acceptance by society, she asked “how many wives in Canada have a legal title to their home over which they preside so that it may be safe from the bailiff in case of financial loss on the part of the husband?” As only one in one hundred women owned their own home, she argued that the proverb “has no significance in our age.” She contended that “If the stronger sex have the almost exclusive right to possess themselves of all the offices, and the professions in the state, surely women make a modest request when they ask that the home should be the legal property of the wife.”

Another article looked toward the position of women in the upcoming twentieth century. Its author wrote:

It is my cherished belief that in the twentieth century there will be no artificial restrictions placed upon women by laws which bar them out of certain employments, professions and careers, or by that public sentiment, stronger than law, which now practically closes to them many paths of usefulness for which they seem to me to be specially adapted. All the most progressive pioneers have ever dreamed of asking is that, in the case of women as in that of men, they should not be hedged about by barriers made by the privileged classes, who, in politics, ecclesiastical, professional and business life, have secured the power to say who shall come in and who shall stay out....I confidently expect that they [women] will win their greatest laurels in the realm of government. Many of the great statesmen of the future will be women; many of the most successful diplomatists will be women; many of the greatest preachers will be women.

The special one-day “Woman’s Edition” of The Evening Journal was a great success. The newspaper sold 3,000 additional copies beyond its normal daily circulation. Many local businesses also supported the issue through their advertisements. It demonstrated that women could do men’s jobs, and excel at them. However, the women’s campaign to establish a Free, or Public Library in Ottawa foundered, at least for a time. The Capital had to wait another decade before Andrew Carnegie, the American millionaire, came to the rescue, and provided the money necessary to build a Public Library.

How have women fared in Canada since that 1895 special newspaper edition in government, in the church, in the courts, and in business? Have the “artificial restrictions” and societal pressures been eliminated? The answer is mixed. Despite the approaching hundredth anniversary of female enfranchisement in Ontario and at the federal level, women still account for a minority of federal Members of Parliament and Senators. Kim Campbell has been the only woman to become Prime Minister of Canada, holding power for only 133 days in 1993. At the provincial level, women have fared better. Kathleen Wynne is the current Premier of Ontario, while women currently head governments in Alberta and British Columbia. For a short period in 2013, six of ten provinces had a woman premier. The ordination of women as ministers or priests has been permitted since 1936 in the United Church of Canada, and since 1975 in the Anglican Church of Canada. The first woman Moderator of the United Church was elected in 1980. The ordination of the first Canadian Anglican bishop occurred in 1994. There are, of course, no woman Roman Catholic priests. At the Supreme Court of Canada, women are well represented, four of nine Justices are women, including the Chief Justice of Canada, the Right Honourable Beverley McLachlin. In business, however, women continue to fare poorly, According to the 2013 Catalyst Census, only 15.9 per cent of board seats of Canadian companies are filled by women.

Sources:

Anglican Church of Canada, 2016. Ordination of Women in the Anglican Church of Canada (Deacons, Priests and Bishops), http://www.anglican.ca/help/faq/ordination-of-women/.

Catalyst, 2013. Catalyst Accord: Women On Corporate Boards In Canada, http://www.catalyst.org/catalyst-accord-women-corporate-boards-canada.

Connelly, M.P. 2015. “Women in the Labour Force,” Historica Canada, http://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/women-in-the-labour-force/.

Evening Journal (The), 1895. “Saturday is the Day,” 11 April.

--------------------------, 1895. “Woman’s Edition,” 13 April.

--------------------------, 1895. “The Woman’s Number,” 15 April.

Gaizauskas, Barbara. 1990. Feed The Flame: A Natural History Of The Ottawa Literary And Scientific Society, Carleton University, Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research, https://curve.carleton.ca/b81c434b-04c8-4886-9c97-cfc1a560ff51.

House of Commons, 1895. Debates, 7th Parliament, 5th Session, Vol. 1, page 2141, http://parl.canadiana.ca/view/oop.debates_HOC0705_01/1081?r=0&s=1.

Ottawa Council of Women, 2016, About, http://www.ottawacw.ca/index.html.

National Council of Women of Canada, 2016. History, http://www.ncwcanada.com/about-us/our-history/.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

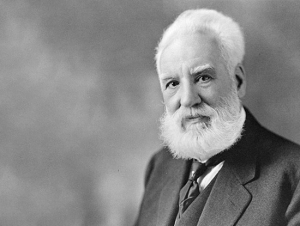

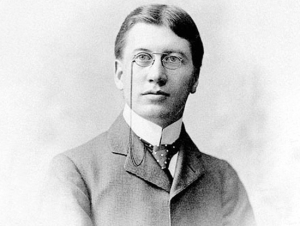

Alexander Graham Bell

9 November 1877

Even though one hundred and forty years have passed since Alexander Graham Bell was awarded a patent for the telephone, there is still bitter disagreement over whether he was truly the inventor of the device. Many others were working simultaneously in the field, including Antonio Meucci, Elisha Gray and Johann Reis. All have claims on being the telephone’s “father.” Even if priority of claim is accorded to Bell, the telephone is hardly an all-Canadian invention as many Canadians believe. According to Bell himself, the telephone was conceived in Brantford but developed at his workshop in Boston. Moreover, three countries can consider Bell to be one of their own as he was born in Scotland, moved to Canada in 1870, but subsequently became a naturalized U.S. citizen. Later, he divided his time between Canada and the United States, dying at his country retreat near Baddeck, Nova Scotia in 1922.

In 2002, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a resolution (No. 269) drafted by Congressman Vito Fossella that in essence gave priority of claim to Antonio Meucci, an Italian inventor who had immigrated to New York in the nineteenth century, based on a patent caveat (a notice of an intention to file a patent) for a “sound telegraph” filed with the U.S. Patent Office in 1871. Worse still, the Congressional resolution insinuated that Bell had stolen Meucci’s invention.

Appalled by this slight on Canadian history and Bell’s integrity, the Canadian House of Commons responded ten days later by passing a parliamentary motion affirming Bell as the inventor of the telephone. While there is no evidence that Bell stole Meucci’s ideas, it’s true that Meucci had been working on developing a similar instrument for some years. However, his patent caveat application did not describe an ability to transmit voices. Unable to afford the small fee to maintain his position, Meucci let his patent caveat lapse.

On the same day that Bell’s lawyer filed a patent application at the U.S. Patent Office in Washington D.C. in February 1876, Elisha Gray submitted a patent caveat for his telephone. The two submissions were remarkably similar. While many accounts say Bell’s submission beat Gray’s by two hours, it’s not clear which got to the Patent Office first. A contrary view has Gray getting his application in ahead of Bell only for it to end up at the bottom of an “In” basket. Regardless, under the law at the time who got to the Patent Office first mattered less than who could demonstrate that he came up with the idea first. Bell successfully made his case to the patent examiner, and was awarded U.S. patent #174,465 in March 1876 for “The method of, and apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically…by causing electrical undulations, similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sound.” His case was strengthened by the fact that Gray withdrew his patent caveat and did not immediately challenge Bell’s claim.

Three days after receiving his patent, Bell produced a functioning telephone. While tinkering with a device at his Boston workshop, Bell’s famous words “Mr Watson, come here, I want to see you.” were heard by his assistant, Thomas Watson, who was working in a separate room down the hall. For that particular experiment, Bell had used a water-based transmitter similar to the one proposed by Gray in his patent caveat—providing Bell naysayers “proof” that he had lifted Gray’s idea. However, Bell never used this type of transmitter in public demonstrations, working instead on the electromagnetic telephone that he demonstrated at the Centennial Exposition in June 1876 in Philadelphia. As an aside, Bell recommended that people answering the phone should say “Ahoy-hoy” rather than “Hello.” This suggestion never caught on, though it did gain a following after its use by “Mr Burns” on the popular television cartoon series The Simpsons.

Needless to say, with the similarities between the Bell and Gray submissions, legal suits began to fly, especially after Gray re-submitted his patent application in 1877. But after two years of litigation, Bell was credited with the invention. This did not stop the legal challenges. Over the next decade, as it became increasingly apparent that there were huge profits to be had in the telephone industry and as new advances in telephone technology were made, the Bell Telephone Company, which was established in 1876 by Bell, his father-in-law, and a Boston financier, was embroiled in hundreds of patent challenges. Some of these law suits went all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. A U.S. Congressional study into the telephone was also undertaken in 1886. Despite all the hearings and all the law suits, the Bell Telephone Company emerged triumphant, its patent rights confirmed.

North of the U.S. border, Alexander Graham Bell received Canadian patent #7,789 for his telephone in August 1877. Canadians did not appear to be greatly impressed by the new technology. In early 1878, The Globe newspaper ran an article posing the question Is the telephone a failure? While saying that the invention was “awe-striking” and that it “had faced little popular or scientific hostility,” the newspaper opined that the telephone had serious operational problems, in, particular interference from other lines and “leakage” that led to “the force of the voice to be lost.” Just as we have concerns today about internet security, the newspaper also fretted about telephone security; telephone lines could be easily tapped.

Alexander Melville Bell, the inventor’s father, wrote a blistering riposte, saying that he regretted “that it should be necessary to defend the merits of so original an invention against the pretensions of pottering envy and wise-after-the-event detraction.” Bell senior called the telephone “a triumphant success,” and that they were “learning and improving,” noting that the problem with interference with other wires had already been remedied.

Notwithstanding this stout defence of his son’s invention, there were no Canadian buyers for Bell’s Canadian patent rights when they came on the market. In 1879, Bell senior, to whom his inventor son had earlier given his Canadian patent rights, could not find a Canadian buyer willing to pay his $100,000 asking price. (This is equivalent to about $2.5 million today.) Instead, he sold them to the National Bell Telephone Company of Boston that was later to be become the American Bell Telephone Company. The American company in turn established the Bell Telephone Company of Canada, based in Montreal, under a federal charter at the end of April 1880.

Ottawa’s introduction to the new communications technology occurred in the fall of 1877. After a demonstration of the telephone at the Ottawa Agricultural Exposition in September of that year by William Pettigrew, a friend of Bell senior, the first telephone line was installed on 9 November 1877, linking the office of Alexander Mackenzie, the Premier of the Dominion of Canada, in his capacity as the Minister of Public Works to the office of Lord Dufferin, Canada’s Governor General, at Rideau Hall. It was a private line. Telephone exchanges that would allow multiple people to be connected to each other through an operator were still in the future.

The contract between Bell senior and the Premier called for the installation of two wooden hand telephones #18 and #19 and two wooden box telephones, #25 and #26, at a fee of $42.50 per annum, payable in advance, due annually on 21 September each year. While the lease was executed on 9 November, the lease was backdated to 21 September so that the honour of Canada’s first telephone lease could go to the government. In actuality, the first Canadian commercial telephone lease was signed by Hugh Cosset Baker, an entrepreneur in Hamilton, Ontario, with the District Telegraph Company in October 1877. The telephone line linked Baker’s office to that of a colleague.

Dave Allston, in his Ottawa blog titled The Kichissippi Museum, recounts a delightful story of the first telephone test call between Rideau Hall and Mackenzie’s office. It seems that Mackenzie’s private secretary, William Buckingham, who was stationed at Rideau Hall for the test, was so rattled by hearing the Premier’s voice coming out of a wooden box, that he flubbed reciting the Lord’s Prayer. Admonished by the Premier, he was forced to repeat himself. Following that embarrassing introduction, the Premier and the Governor General spoke to each other for the first official telephone call.

Makenzie was not terribly impressed with the new-fangled communications instrument owing to its unreliability. It must also have been awkward to use; the same hole was employed for both listening and talking. But when the Premier asked for the telephone to be removed, he was overruled by the Governor General. Apparently, Lady Dufferin, the Governor General’s formidable consort, was much taken with the telephone. According to a 1961 Citizen article she would sing and play the piano into the phone to people at the Premier’s office. Captain Gourdeau of the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards would sing back to her.

With the invention of the telephone exchange—the first exchange in Canada (and, indeed, the first in the British Empire) was installed in 1878 in Hamilton, Ontario—a telephone service similar to what we know today was made possible. In the major Canadian cities, service was initially provided by two competing companies—the Dominion Telegraph Company that marketed Bell equipment and the Montreal Telegraph Company that marketed Edison equipment. This competitive struggle between the two companies paralleled the patent war underway at that time in the United States between the Bell Telephone Company that naturally used Bell equipment and the Western Union Telegraph Company that used Edison equipment. Inconveniently to telephone users, subscribers of one service could not make or receive telephone calls from the other service. The Dominion Telegraph Company opened its Ottawa telephone exchange managed by Warren Soper in January 1880. Its first telephone directory consisted of two pages with less than 80 subscribers. The Montreal Telegraph Company followed suit a month later with its Ottawa office managed by Thomas Ahearn.

Almost immediately after it was established in April 1880, the Bell Telephone Company of Canada purchased the Dominion Telegraph Company. Later that same year, it also acquired the Montreal Telegraph Company, thereby uniting the two large Canadian providers of phone services under one company, and in the process stopping the ruinous war between the two companies that brought them to the point of bankruptcy. In Ottawa, the new Bell Telephone Company was managed by Thomas Ahearn who later went on to fame and fortune as Ottawa’s electricity baron when he joined forces with Warren Soper to create the electrical firm called Ahearn and Soper.

Through the 1880s, the Bell Telephone Company successfully saw off other challengers in the Ottawa market through acquisitions and legal threats. Mid-decade, the company issued a public notice that it would prosecute anyone using the “Wallace” Telephone, or any other telephone provider that infringed on patents originally granted to Bell, Edison, Berliner, and others,” that were still in force and were owned by the Bell Telephone Company of Canada. Instead, the company advertised “instruments under the protection of company patents and are entirely free of risks of litigation.” Would-be buyers of competing equipment were also reminded that such telephones “will not be allowed to connect…into the Company’s lines or exchanges.” The announcement was signed by Thomas Ahearn, Bell’s agent in Ottawa.

By early 1886, Bell Telephone had roughly 400 telephone subscribers in Ottawa, and was growing rapidly. (There were 1,400 subscribers in Montreal.) In October the following year, direct long distance service between Ottawa and Montreal was inaugurated. Previously, callers were routed through Brockville and Prescott. Within weeks, a rapid increase in traffic led to plans for additional long distance lines. In 1888, new telephone poles were erected on Rideau Street and Sussex Avenue to replace old ones that were too short to carry the increasing number of wires. The Ottawa Journal complained that “a telephone company has been stringing wires all over the streets at its own sweet will, without the slightest reference to any civic authority.” In April 1900, Ottawa was the first Canadian city to do away with the old hand-cranked telephones. With batteries installed in a central office instead of in a customer’s telephone, a person could now reach an operator by simply picking up the receiver. The familiar, table-top telephone that would dominate the telephone scene for the next century had arrived.

Sources:

Allston Dave, 2015. “When the telephone arrived in Kitchissippi,” The Kitchissippi Museum.

Bell Homestead: National Historic Site, City of Brantford, 2016. Telephone History.

BCE, 2016. History: From Alexander Graham Bell Until Today.

CBC Digital Archives, 2016. Canada Says Hello: The First Century of the Telephone.

Canadian Parliamentary Motion on Alexander Graham Bell, 2016. Wikipedia.

Casson, Herbert N. 1910. The History of the Telephone.

Globe (The), 1878. “Is The Telephone A Failure,” 4 January.

———, 1878. “The Telephone,” 12 January.

———, 1883. “Discovery of the Telephone: Interview with Pref. Bell,” 1 September.

Globeandmail.com. 2016, Bell Canada: The History of One of Canada’s Oldest Companies.

Mccord Museum, Operator. May I help you?: Bell Canada’s 125 years.

Motherboard, 2012, No-one remembers who invented the telephone,” 17 July.

Ogle. E. B. 1979. Long Distance Please: The Story of the Trans-Canada Telephone System, Toronto: Collings Publishers.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1961. “Line Veterans Revive Old Days,” 28 October.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1886. “Public Notice,” 1 February.

—————-, 1886. “Ottawa to Montreal,” 21 April.

—————-, 1886. “Montreal and Ottawa,” 22 July.

—————-, 1887. “Another Telephone Line,” 22 November.

—————-, 1888. “The Overhead Network Growing,” 5 June.

—————-, 1888. “Civic Notes,” 25 June.

Stritof, Bob and Sheri, 2006. “Who Really Invented The Telephone,” Telephone Tribute.

Uren, Janet, 2006. “http://wordimage.ca/files/Ahearn.pdf">The man who lit up Ottawa,”.

U.S.Patent Office, 1876. Improvements in telegraphy, Patent #174465, 7 March.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Santa Claus Comes to Town

24 December 1896

It’s hard sometimes not to get a little cynical about Christmas. Even before the last Halloween candy or pumpkin pie is consumed, it seems that stores have already put up the lights and tinsel of Christmas. Television advertisements urge us to buy things that neither we nor our family need. Christmas catalogues and store flyers clog our mailboxes, both real and virtual. Every shopping centre has its mall Santa, complete with faux ice palace, throne, green-clad helpers, and a posted list of times of when that jolly old elf dressed in red polyester and a fake white beard will be there to hear children’s wish lists. Christmas craft fairs and Santa Claus parades abound. For 2016, a local tourism site listed no less than seventeen Santa parades in the Ottawa area, most taking place in November to help rev up the Christmas spirit and encourage us to shop.

This is not to say the “good old days” were necessarily any less commercial. In the lead-up to Christmas 1896, Bryson, Graham Company, a large department store on Sparks Street, billed itself as the “Headquarters of Santa” and advertised “Special Xmas Offerings to the Little Folks.” For boys, these included small iron trains for 25 cents, fire ladder wagons with horse for $1.45, and tops, “some musical, some goers,” for 50 cents, as well as “spring guns, harmless pistols, and cannons.” (One hopes that the spring guns and cannons were also harmless.) For little girls, there were doll perambulators for 25 cents, and “very pretty” doll parlour suites for 15 cents or 25 cents. Games of all kinds, including Bagatelle [a forerunner of pinball], Parlour Croquet, and Go Bang [similar to Go], were also “expressly priced for Christmas.” The store also told shoppers not to forget while they were at the store to buy three dozen oranges or five pounds of candies for 25 cents.

Santa Claus in the 1890s

Santa Claus in the 1890s

The Ottawa Evening Journal, 21 December 1895John Murphy & Company, another big Ottawa retailer, urged “everyone to take a stroll round our store and see the sights of Xmas displays. Everything is looking marvellous.” It advertised “Christmas Dresses at Santa Claus’ prices.” For one day, full length dress robes were only $2.15. Best quality dresses were $3.00. Camel hair cloth was marked down to 50 cents a yard, from 75 cents, while brown and grey all wool homespun was reduced to 75 cents a yard from $1.25. On Christmas Eve, the store advertised a free bottle of perfume with every pair of kid gloves purchased. In the toy department, one thousand games were on sale at half price. While 40 extra staff had been hired for the day, it warned that “Christmas Buyers should do their shopping early” to avoid the rush and to get “better service and better suited.” Store hours were extended to 10pm for the convenience of shoppers, as well as, of course, to provide more opportunity for the store to pry hard-earned cash from the wallets and purses of Ottawa citizens.

Despite the commercialism of Christmas, then and now, once in a while something happens that restore one’s faith in the generosity of mankind, and the almighty dollar is pushed aside for a time. One such occasion occurred in 1896. Three days before Christmas, the Ottawa Evening Journal received a mysterious, little letter from Santa Claus. Dated the previous week from the North Pole, the letter read:

I have arranged to visit Ottawa on Thursday, the day before Christmas, and wish you would let all the little children know that I shall appear on the principal streets during Thursday afternoon on top of an electric [street]car.

Santa added that he would visit Sparks and other streets but would have to disappear by 4.30pm so that he could prepare for the visits he intended to make “that night to the homes of all Ottawa children who are good.” He closed by promising that he would telegraph ahead to tell people his progress on his trip south. The Daily Citizen remarked that Santa’s visit was not connected to any advertising scheme but was “simply the outcome of a desire upon the part of an Ottawa gentleman that the children of the city may see Santa in person.”

The following day, a second letter appeared. Writing from 31 Mile Lake, north east of Gracefield, Quebec, Santa announced his arrival in the region, saying that he would be in Ottawa the next afternoon.

I am bringing my best reindeer and will have him with me on top of a special electric car. I am also bringing with me a couple of thousand oranges and will distribute them from the car to the little boys and girls.

Santa Claus's Streetcar, 24 December 1896

Santa Claus's Streetcar, 24 December 1896

Courtesy of the City of Ottawa Archives, RG045/CA001513He also announced his stops in the city, starting at 2.45pm at the corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets, followed by the corner of Rideau and Dalhousie at 3pm, corner of Queen Street West and Bridge Street, Chaudière, at 3.15pm, corner of Richmond Road and Albert Street at 3.20pm, corner of Bank and Maria [now Laurier Avenue] Streets at 3.35pm and, finally, at the corner of Bank and Ann [now Gloucester Avenue] Streets at 3.45pm. He would then return to the Post Office and immediately disappear. He apologized to the children of New Edinburgh that he was unable to make it to the town since his reindeer’s horns were so high he couldn’t take his car through the bridges. However, he promised to make his usual visits that night to the homes of all good boys and girls who have gone to bed early and were fast asleep. He asked grown-ups to tell their youngsters to look out for him on Thursday afternoon as it would be his only appearance in Ottawa.

The next day, Christmas Eve, Thursday, 24 December 1896, the excitement in the city was palpable. Thousands of people of all ages converged on the street corners where Santa Claus was scheduled to appear. They were not disappointed. The Ottawa Evening Journal noted that “the rules of etiquette, or whatever else is supposed to govern the movements of that most mysterious personage Santa Claus, and which from the oldest tradition led most individuals to believe that his visits are of a midnight nature, were rudely broken today.” Right on the scheduled time, Father Christmas arrived. “For convenience sake in transportation about the city streets,” his sleigh and reindeer were mounted on a streetcar of the Ottawa Electric Railway, which was decorated as a snow-covered cabin complete with chimney, and festooned with garlands. On its sides were signs reading “Merry Xmas To All.”

Santa himself was dressed in a fur cap and a long fur coat—very different from the red and white coated Saint Nick described in the classic Clement Clarke Moore poem ‘Twas the Night Before Christmas, and popularized by Coca Cola in its commercials. He did, however, have white whiskers, though press reports don’t mention if he also had “a little round belly that shook like a bowl full of jelly.”

Who was that Ottawa gentleman who brought Santa Claus to Ottawa for his first ever official visit to the nation’s capital (outside of his usual Christmas Eve tour of Ottawa rooftops, of course)? The answer was Warren Soper, the wealthy industrialist who, with his partner Thomas Ahearn, owned the city’s streetcar company, as well as other area businesses. Mobbed by adoring children, their parents and grandparents, Santa Claus handed out more than three thousand oranges to the city’s little boys and girls during his short stay. The Ottawa Evening Journal said that the visit was “quite the treat even for the grown people to see a real Santa Claus and such a good and generous one at that.”

The Daily Citizen opined that “No wretched doubter will ever again be able to hold his head in Ottawa and say that good, kindly Santy did not exist.”

Sadly, among the crowds of people that came out to meet the visitor from the North Pole, there was a grinch who stole $4 from the purse of poor Miss Scheik of 20 Keefer Street, New Edinburgh while she waited to see Santa at the corner of Dalhousie and Rideau Streets.

Sources:

Daily Citizen (The), 1896. “Santa Claus in Ottawa,” 22 December.

———————–, 1896. “Santa Clause [sic] Coming,” 24 December.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1896. “Santa Claus Coming,” 22 December.

————————————, 1896. “Special Xmas Offerings for the Little Folks,” 22 December.

————————————-, 1896. “Santa’s Trip To Ottawa,” 23 December.

————————————-, 1896. “John Murphy & Co, Seasons Greetings,” 23 December.

————————————-, 1896. “Santa Comes To Town,” 24 December.

————————————-, 1896. “Entre Nous,” 26 December.

————————————-, 1896. “Santa’s Appearance,” 26 December.

————————————-, 1896. “Jottings About Town,” 28 December.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Hanging of Patrick Whelan

11 February 1869

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, the much revered Canadian statesman, nationalist, poet, and orator, died by an assassin’s bullet on 7 April 1868 as he was entering his boarding house on Sparks Street. Immediately, suspicion fell on the Fenian Brotherhood, a secretive group of Irish extremists founded in the United States mid-19th century, but with cells and sympathizers in major Canadian cities, including Montreal, Toronto, and Ottawa. At that time, waves of poor, Irish immigrants were flooding North America each year to escape the potato famine, poverty, and British neglect and misrule in Ireland. Bringing anti-British sentiments with them, most settled in the major U.S. northeastern cities. Between 1866 and 1870, armed groups of Fenians, many battle-hardened from service in the U.S. Army during the American Civil War (1861-65), launched a series of raids into Ontario and Quebec from the United States in an attempt to hold the country hostage and force Britain to free Ireland. In one of the worst of these incursions, some 1,300 Fenian soldiers led by a former U.S. Civil War colonel captured Fort Erie in southern Ontario in June 1866 before being forced to retreat back to the United States.

McGee, an Irish radical himself during his younger days, had provoked the wrath of Irish extremists when he became their most outspoken critic. Being a senior member of the Canadian government, McGee was seen as a traitor to the Irish cause, a sell-out to British interests. What probably hurt the most was that McGee ridiculed the Fenians, calling them deluded and foolish. He also poked holes in Irish nationalist shibboleths, arguing that Canada under the British Crown was a far better place for Irish immigrants to settle than republican United States. Instead of discrimination and exploitation, Irish Catholics would find acceptance and equality. In Canada, Irish settlers were becoming prosperous landowners, and were well represented in the professions and business.

After McGee’s assassination, Ottawa police swooped down on known Fenian sympathizers, arresting several and held them for questioning. But a sandy-haired, whiskered man named Patrick James Whelan quickly became a subject of interest, and was charged by Detective Edward O’Neill with McGee’s murder. Police searched Whelan’s room in a nearby hotel and found copies of the Irish American, a Fenian newspaper, that had supported the invasion of Canada. Also discovered were Whelan’s membership cards and badges for radical Irish societies, and, most incriminating of all, a Smith & Wesson revolver. Power residue suggested that it had been fired within the previous two days. Later, evidence emerged that Whelan had been stalking McGee, twice going to his boarding house in the days preceding the murder. He had also watched McGee from the House of Commons visitors’ gallery on the night he died. In an odd encounter, Whelan had shown up at McGee’s Montreal home late at night the previous New Year’s Day. When McGee’s half-brother opened the door, Whelan, using an assumed name, had warned the family that their house was about to be fire bombed. Fortunately, nothing happened.

The ensuing trial was a sensation, pitting two of Canada’s top legal minds. Ironically, for the prosecution was James O’Reilly, an Irish, Catholic, Queen’s Counsel from Kingston, who excluded all Catholics from the jury on the grounds that they might be prejudiced in favour of Whelan. For the defence was John Hillyard Cameron, grandmaster of the Orange Order, a rabidly Protestant, Loyalist society. He took the job of defending Whelan on principle, and for the money; his considerable fees were paid for by funds raised by Irish Catholics who feared hasty justice.

There was general agreement that both attorneys were in top form. The defence counsel proved that six weeks before McGee’s murder a maid at the hotel where Whelan had been staying had accidentally discharged his revolver when she found it in his bed. But this did not explain the powder residue which experts testified was no more than two days old. More successfully, Cameron rubbished the supposed eye-witness testimony of Jean-Baptiste Lacroix who didn’t show up at the police station until two weeks after the assassination. Lacroix said he saw a small, whiskered man follow McGee down Sparks Street to McGee’s boarding house. But in reality, Whelan was a big man, taller than McGee. He also said McGee had been wearing a black hat whereas the hat had actually been white. The defence also presented witnesses who cast doubt on Lacroix’s reliability, and said that he had only come forward for the reward money—$10,000, a considerable sum in those days. Harder to shake was testimony that Whelan had repeatedly threatened to kill McGee, and that Whelan’s New Year’s Day visit to McGee home was an aborted assassination attempt. Even more damning was testimony by Gaelic-speaking Detective Andrew Cullen who, when planted in a nearby cell to Whelan’s in the Ottawa jail, overheard him say to a fellow prisoner “I shot the fellow…I shot him like a dog.”

Following six days of testimony, and superlative closing addresses by the two attorneys, the jury found Whelan guilty of murdering Thomas D’Arcy McGee. Whelan was sentenced to hang by the neck until he was dead. Defence counsel appealed on the grounds that the judge had incorrectly ruled that Whelan couldn’t challenge potential jurymen for cause until after he had exhausted his 30 peremptory (i.e. without cause) challenges. The appeal failed. Two days before his date with the hangman, Whelan reiterated his innocence. He told his wife that it was better to hang than to be an informer. Whelan also said that he knew who shot McGee because he had been there.

After sleeping soundly for six hours, Whelan was roused at about 5.00am on 11 February 1869. After Mass in the prison’s chapel, he had some breakfast. Despite a driving snowstorm, people started to arrive at the prison at 9.00 to get a good view of the gallows. By 10.30, a rowdy throng of some 8,000 people were crowded into the streets in front of the jail. The Globe newspaper was shocked that many respectable women were in the crowd, along with hundreds of boys and girls. At 11.00, the sheriff appeared with Whelan on the balcony, with three priests in surplices. The bound Whelan looked “pale and excited” with beads of sweat on his forehead. After repeating the Pater Noster, Whelan moved to the railing to address the crowd. He begged pardon for any offences he might have committed and forgave all parties who had injured him. His last words were “God save Ireland and God save my soul.” He then stepped back over the drop.

At 11.15, the executioner drew a white bag over Whelan’s head and adjusted the rope. He then opened the trap door, and Whelan dropped to his death. It was not an easy one. Many in the crowd clapped as Whelan kicked his heels in the air before expiring. It was the last public hanging in Canada.

Many have subsequently questioned Whelan’s guilt and the fairness of his trial. Anti-Fenian feelings were running high in Canada at the time, and McGee had been a popular politician. The evidence, while compelling, was largely circumstantial; the only eyewitness was unreliable. Jailhouse confessions also have a dubious record of veracity. Moreover, while there were no complaints about how the trial was handled, even by Irish nationalist papers, it was flawed by today’s standards. Sir John A. Macdonald, the Attorney General as well as Premier, sat beside the judge during Whelan’s trial. While his presence didn’t raise negative comment at the time, it would be seen as prejudicial today. As well, the judge, William Richards, who presided over the trial had been appointed to the Court of Appeal by the time defence counsel launched an appeal. As a consequence, he sat on the court that listened to the appeal of his own ruling—a clear conflict of interest. He also sat on the bench when a subsequent appeal was made. In both cases, he made the deciding vote. However, the breach in court procedure regarding the selection of a jury by the defence was highly technical, and it’s hard to see how it might have affected the course of the trial.

Modern-day ballistic tests were conducted in 1973 on Whelan’s Smith & Wesson revolver and the bullet that killed McGee. However, owning to corrosion, it was impossible to conclusively say that the bullet had been fired from McGee’s gun. It would, of course, have be impossible for the tests to determine that it was Whelan’s hand that had held the gun.

Whelan was likely a Fenian, and he certainly held a grudge against McGee. His own words prior to his execution placed him at the scene of the crime. But there is no hard evidence that he was the triggerman.

The fascinating story of Whelan’s innocence or guilt is the subject of a play Blood on the Moon, a one-man production written and performed by Pierre Brault. The play premiered in 1999 in Ottawa in the same building that once was the court house where Whelan’s trial was held and adjacent to the prison where Whelan was hanged.

Sources:

CBC, 2009. “Shadows on Sparks Street,” Ideas with Paul Kennedy.

Slattery, T.P., 1968. The Assassination of D’Arcy McGee, Doubleday Canada Ltd. Toronto.

Scott, C., 2014. “Patrick Whelan,” Ottawa Stories, The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Sleeping Dog Theatre, 2004, Blood on the Moon.

The Globe, 1869. “Execution of Whelan: Closing Scenes and the Agony of Death. A Short Speech and No Confession,” 12 February.

The Montreal Gazette, 1973. “Ballistic Experts Not Sure on Gun that Killed McGee,” 19 October.

Wilson, David. A., 2011. Thomas D’Arcy McGee, Volume 2, The Extreme Moderate, 1857-1868, McGill-Queen’s University Press, Montreal & Kingston.

Image: Library and Archives Canada, #3412296.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Eastview Birth Control Trial

17 March 1937

Birth control is an accepted part of modern life by all except the most religiously conservative. Competing brands of condoms in garish packages jostle for attention on the druggist’s shelves, while contraceptive pills, easily obtained by prescription, are covered by health insurance plans. It might therefore come as a surprise to learn that as recent as 1969 contraceptives were illegal in Canada. Even the dissemination of basic information about birth control was prohibited unless it could be shown to be “in the public good.” One of the big steps along the long road to repealing the law took place in Ottawa in the 1930s. However, the landmark legal decision that set change in motion had little to do with a woman’s right to control her body. Far more important were efforts to control the size of Canada’s poorer classes.

On 14 September 1936, Dorothea Palmer was arrested after visiting a welfare mother in the community of Eastview, now called Vanier. A week before her arrest, Palmer, who had received some training as a nurse in her native Britain before immigrating to Canada in 1928, had taken a part-time job in Ottawa with the Parents’ Information Bureau (PIB). The PIB, started in 1930 by Alvin Ratz Kaufman, a wealthy, Kitchener-based industrialist and philanthropist, provided poor families with pamphlets about birth control, as well as sample contraceptives. PIB workers would make house calls on poor mothers, typically by referral of a doctor or friend. After a mother filled out an application form, which asked a slew of questions, including her race, the number of pregnancies she had had, her husband’s occupation and salary, she could acquire contraceptives through mail order from the PIB for a small fee, or for free, if she were destitute.

Palmer was arrested by Constable Emil Martel and brought to the police station where she was questioned by Chief Richard Mannion. Believing she was not going to be charged, Palmer freely told the police what she was doing in Eastview, adding that “A woman should be master of her own body.” Mannion called the Crown Attorney who charged her with three counts under Section 207(c) of the 1892 Criminal Code for selling, advertising, and disposing of contraceptives. Although Palmer figured she would get in trouble with the Catholic Church, she was surprised to have been arrested. PIB workers had been told that what they were doing was legal as their actions were covered by the “public good” clause of the Act. However, the broad applicability of the clause, which was intended to protect doctors, was untested in court. Eager to set a legal precedent, Kaufman provided the $500 bail for Palmer’s release, and paid $25,000 for a top-rate legal team for her defence.

The trial, one of the longest in Canadian history, lasted six months. Witnesses, included social workers, clergy, and doctors, as well as twenty-one poor, francophone women visited by Palmer in Eastview. Judge Lester Clayton quickly dismissed two charges against Palmer, those of selling and disposing of contraceptives devices, due to lack of evidence, leaving the trial focused on whether or not the distribution of pamphlets on birth control fell under the “public good” clause of the Act.

The prosecution relied on medical opinions to show that birth control was unnatural, or dangerous, and that the distribution of birth control literature by lay people was not in the public interest. One obstetrician-gynaecologist called by the Crown argued that the control of a woman’s organs was above man’s law, and that birth control would lead to a woman experiencing “pathological conditions.” Another, a professor of gynaecology at the University of Montreal, spoke against all forms of birth control other than the rhythm method. On cross examination, he admitted that his objection was religious. Some doctors, while supporting birth control for existing mothers who wanted to space future pregnancies, argued that it should be handled solely by medical professionals. However, the testimony of medical experts was undermined when they acknowledged that they actually knew little about birth control; the subject was not taught in medical school.

Palmer’s defence team focus its arguments on the supposed sociological and economic virtues of birth control rather than human rights. Although the directors, both women, of the Toronto and Hamilton birth control clinics spoke about a woman’s reproductive rights, and the welfare of mothers, as did the Eastview mothers who didn’t want more children, their testimony was overshadowed by eugenic views expressed by male witnesses.

Prior to World War II, eugenics was a respected scientific theory, based on Darwinism, that aimed to improve mankind through selective breeding for beneficial human characteristics (positive eugenics) and the discouragement of negative traits through birth control or sterilization (negative eugenics). The Eugenics Society of Canada, established in the early 1930s, lobbied for the establishment of a national policy of “race betterment” by enacting legislation to “safeguard racial progress.” Many respected progressive Canadians were eugenics supporters, including Tommy Douglas and Nellie McClung. Both Alberta and British Columbia enacted legislation permitting the sterilization of unfit and feeble-minded individuals that wasn’t repealed until the early 1970s. Unfortunately, the terms “unfit,” and “feeble-minded” were open for interpretation. For many, racial improvement meant advancing the white, Anglo-Saxon, protestant “race” at the expense of others. Eugenics supporters also argued that the upper and middle classes were being outbred by the poor and mentally ill, leading to genetic, social, and economic disaster. To correct the birth differential, birth control should be made available to the masses. The reputation of eugenics crashed during World War II when Nazi Germany used the theory as justification for its racial policies that led to the death of millions in its concentration camps.

A number of prominent Canadian eugenicists testified at Palmer’ trial, including Alvin Kaufman, Treasurer and founding member of the Eugenics Society of Canada, Dr. William Hutton, the Society’s president as well as the Brantford Medical Doctor of Health, and the Reverend Dr. C.E. Silox, the Secretary General of the Social Service Council of Canada. Both Kaufman and Silox testified that since poor, unemployed workers were having large families, the only alternative to birth control was revolution or communism. Silox raised the Malthusian spectre of uncontrolled population growth requiring state intervention, or the “invention of new deadly diseases, more terrible famines, and bigger and better wars” to stop it. If that wasn’t controversial enough, Silox argued that French Canadians were deliberately outbreeding English Canadians while driving down their standard of living. By giving poor francophone families access to birth control, he claimed that Anglo-French tensions would be eliminated, and English dominance maintained. Le Droit, Ottawa’s French language newspaper, angrily retorted that the trial was all about killing French Canadians in the womb.

Dr. William Hutton presented dubious statistics purporting to show that the average intelligence of Canadians was declining due to a higher fertility rate of the less intelligent, a view supported by a University of Toronto psychiatrist who argued that Canada faced a biological crisis as a consequence. Further testimony by a Toronto economist underscored the burden to society of supporting the unemployed of Eastview, noting that the community’s unemployment rate was more than double the national average, and that births in the town outnumbered deaths by more than 150 per year. Similarly, the Secretary of the Toronto District Labour Council argued that birth control should be used to “govern the level of the nation’s population” until surplus workers were absorbed, or the economic system changed.

On 17 March 1937, Judge Clayton, swayed by the economic and social arguments made by the defence, ruled that Dorothea Palmer’s actions were indeed in the public interest. In his summing up, there was no mention of women’s rights. With the subsequent appeal by the Crown dismissed, Clayton’s ruling opened the door a crack for birth control in Canada.

Sadly, for all her courage, Palmer received little support from her husband, relatives and Church who disapproved of her stand. During her trial, a stranger, passing on the street, slapped her face. Palmer received obscene phone calls at all hours, and was sexually assaulted by a man who told her “I’ll show you what it’s like without any birth control.” Fortunately, a knee in the groin and a punch in the face stopped her assailant. After the trial, she quit the PIB, saying her work was done, and faded into obscurity. Palmer, a pioneer for women’s rights, died in 1992.

Sources:

Annau, Catherine, 1994. “Eager Eugenicists: A Reprisal of the Birth Control Society of Hamilton,” Social History, Volume XXVII, Number 53, p. 111-133.

Bonikowsky, Laura, 2011, “It’s About Control: Dorothea Palmer and Contraception,” Historica Canada Blog, 13 September.

Dodd, Dianne, 1983, “The Canadian Birth Control Movement on Trial, 1936-37,” Social History, Volume XVI, Number 32, p. 411-28.

Jasmin, Olivier, 2012. Eugenics in Canada.

Martel, Marcel, 2014, Canada The Good, A Short History of Vice since 1500, Wilfrid Laurier University Press, Waterloo.

National Post, 2012. “Canadians airbrush the truth Tommy Douglas’s enthusiasm for eugenics: MD,” 14 March.

Revie, Linda, 2006. “More Than Just Boots! The Eugenic and Commercial Concerns behind A. R. Kaufman’s Birth Controlling Activities,” Canadian Bulletin of Mental Health, Volume 23:1, p. 119-143, file:///C:/Users/User/Downloads/1269-1271-1-PB.pdf.

The Globe, 1936. “Palmer acquitted on one birth control count,” 21 October.

—————, 1936. “Public Good, Is Defense Point in Palmer Case,” 2 November.

—————, 1936. “Birth Control or Red Regime, Pastor States,” 3 November.

—————, 1936. “Rabbi, Pastors, Doctor Defend Birth Control,” 6 November.

—————, 1937. “Deny Charge of Obscenity,” 2 February.

The Globe and Mail, 1937. “Birth Control Case Dismissed,” 18 March.

———————–, 1978. “Did Dirty Work for men at trial, pioneer of birth control says,” 30 November.

Image: http://www.intlawgrrls.com/2010/09/on-september-14.html.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Galloping Gourmet

30 December 1968

Long before Jamie Oliver or Gordon Ramsay worked their culinary magic on television, there was Graham Kerr, a.k.a. The Galloping Gourmet. While Kerr (pronounced “Care”) was not by any means the first gourmet chef to appear on the small screen—that honour goes to James Beard in 1946—he, like Julia Child, did much to popularize fine cooking in North America. At a time when the acme of fine dining for many Americans and Canadians was a hamburger topped with bacon and cheese, and Italian cuisine was a can of Chef Boyardee spaghetti, Kerr introduced millions to the likes of Lamb Apollo, Red Snapper in Pernod, Crab Captain Cook, and Gateau Saint Honoré. His zany antics, lightning fast wit and double entendres delivered while chopping and sautéing delighted television audiences around the world. At the peak of his popularity in 1970, his television show, The Galloping Gourmet, was seen in thirty-eight countries, including the United States, Canada, Britain, Germany, France and Australia, with more than 200 million viewers. Dubbed into French, it was called the Le Gourmet Farfelu on the CBC’s French-language network. Amazingly, The Galloping Gourmet was made in Ottawa.

Graham Kerr - The Galloping Gourmet

Graham Kerr - The Galloping Gourmet

The Cooking ChannelThe British-born Kerr learnt how to cook as a teenager during the late 1940s in the kitchen of his parents’ hotel. After five years in the British Army’s catering corps, he moved to New Zealand and joined the New Zealand Air Force as a catering adviser. It was in New Zealand in 1959 that he got his first televised cooking show—Eggs with Flight Lieutenant Kerr. Performing in uniform, the young Kerr received a munificent $25 for his weekly television programme. Spotted by a promoter with links to Australia, Kerr was launched on Australian television with a programme called Entertaining with Kerr in 1964 on the Ten Network.

In 1968, he and his wife Treena came to Ottawa to film The Galloping Gourmet for Freemantle International, a television production/distribution company. Although the show was aimed at an American audience, the Kerrs chose Canada as their base of operations because they wanted to bring a British/Australian flavour to the show that they thought might be lost in an American-made production. Also, Canada had first class television studios that could make colour programmes. Colour television had been introduced to the Canadian market in 1966, whereas Australian television was still operating in black and white. To make the daily 23-minute programme, the Kerrs went to the CJOH studios located at the corner of Merivale Road and Clyde Avenue in Ottawa. Then owned by Bushnell Communications, CJOH was the third busiest television production centre in Canada. Under the direction of Bill McKee, an exceptional staff of 160 people, of whom 100 were directly in production, worked ten hour days seven days a week producing as many as dozen different television series as well as films for government departments. In a 1970 interview, Kerr stated that CJOH had the “finest” television crew with whom they had ever worked.

Production of The Galloping Gourmet began in the summer of 1968, making six shows a day, thirty shows per week. It was a gruelling schedule. The Kerrs worked as a team, Graham in front of the camera, and Treena as the show’s producer. Initially, there was little to distinguish the new show. Indeed, the television studio’s audience relations staff found it difficult to find people willing to fill the seats in the studio equipped with a full kitchen with an autumn brown fridge and stove, dining room, bar and wine rack. However, this was to quickly change.