The Main Branch of the Ottawa Public Library welcomed us back on Saturday, September 28, a beautiful fall afternoon, for our first in-person English language Speaker Session of the 2024 / 2025 series. We were pleased to partner with the Workers History Museum for this presentation and honoured to have their President, David Dean, on hand to introduce our guest speaker. Brian McDougall describes himself as a “socialist historian”, one who asks different questions and so draws different conclusions than main-stream historians. David Dean described Brian as a former civil servant, educator, author and activist with a dedication to public history. Brian related the stories of two early strikes and how they are now remembered. His audience of 40 was enthralled.

Brian began by giving us some background on the match industry at the turn of the 20th century. Prior to the general electrification of the world, matches were a critical product and the E. B. Eddy factory in Hull was at one time the largest match making factory in the British Commonwealth. The work, which involved men cutting the matches and women making the packaging and packing the matches into the boxes, was not only low paying, as was all industrial work at that time, it was also highly dangerous. Prior to the First World War, matches were made using white phosphorous, a highly flammable and poisonous chemical which resulted in a condition called phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, (aka Phossy Jaw), in which the vapours from the white phosphorous destroyed the bones of the jaw. Fire was another ever-present danger.

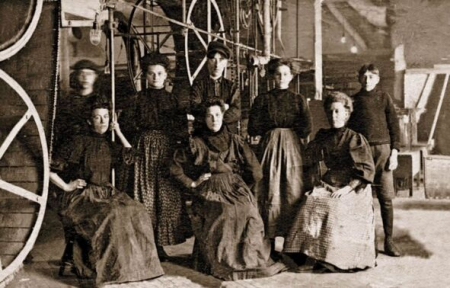

The ‘Match Girls’ (les Allumettières) were young, poorly educated, French, Catholic women, forced into the work force by the low wages paid to all members of the working class. Their living conditions were appalling, characterized by large families inadequately housed, with poor sanitation, bad nutrition and rampant disease. Working women held the dual responsibilities of contributing to the family income while also caring for all of its members.

Brian told us, perhaps surprising many, that the women match makers at E.B. Eddy were unionized: l'Union ouvrière féminine de Hull. The women, however, were not permitted to negotiate for themselves, this being done “on their behalf” by male union leaders and the Oblate Fathers, the church being central to all aspects of life in that community. The negotiators believed in a strategy of progress through cooperation and conciliation with the English ownership rather than a strategy of confrontation.

A heavy demand for matches, led the company, in October 1919, to demand that the women work double shifts. The women refused and were locked out. After some discussions with the male leadership, the company offered a shorter work week and an increase in wages, but demanded the right to change work hours as they wished and included a “yellow-dog” clause in the proposed settlement that would ban the women from union membership. The women refused. Shortly thereafter an agreement was reached in which the women would work double shifts for a period of 4 months, would receive a 50% pay increase (little in real terms) and would retain their union membership. This was accepted and work resumed.

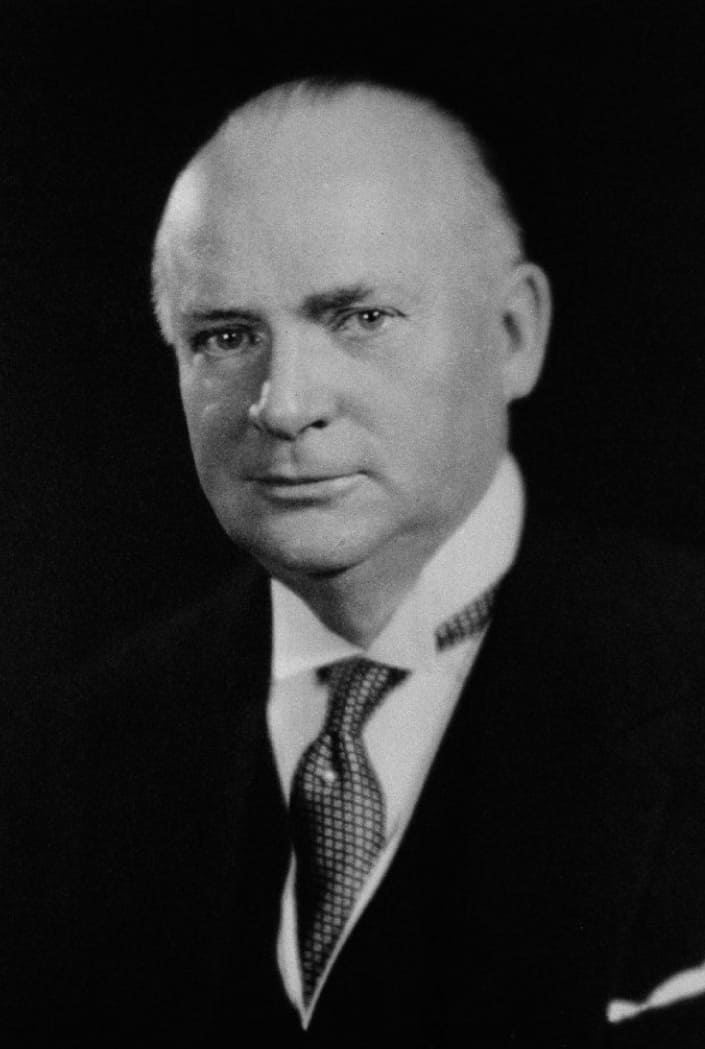

Richard Bedford Bennett, LAC 1930.Brian explained that labour issues came to a head again in September 1924, this time driven by a drop in prices for matches. By now the company had left the control of the Eddy family, with future Prime Minister R. B. Bennett being the principle owner, who held that he was not bound to agreements signed by the previous owner. The company demanded a 50% pay cut and to seize the hiring process from the women supervisors, with the intention to hire non-French Catholics and so break the union. In response, union president, Donalda Charron led the women out on strike. The women picketed, fundraised, held 9 public meetings to explain their position, and so received both financial support and donations of food from the local communities. This included printed support from the French language newspaper Le Droit.

Richard Bedford Bennett, LAC 1930.Brian explained that labour issues came to a head again in September 1924, this time driven by a drop in prices for matches. By now the company had left the control of the Eddy family, with future Prime Minister R. B. Bennett being the principle owner, who held that he was not bound to agreements signed by the previous owner. The company demanded a 50% pay cut and to seize the hiring process from the women supervisors, with the intention to hire non-French Catholics and so break the union. In response, union president, Donalda Charron led the women out on strike. The women picketed, fundraised, held 9 public meetings to explain their position, and so received both financial support and donations of food from the local communities. This included printed support from the French language newspaper Le Droit.

After two months the male negotiators and the company reached a settlement in which the women would return to work at their same hours and rate of pay. The union would remain in place. No improvements in working conditions were achieved. Donalda Charron was not rehired and the women supervisors lost control of the hiring process. The women supervisors were later fired and the union was lost.

The two strikes of 1919 and 1924 were the first by solely women workers in the Province of Quebec and in this area. The match works was sold in 1927 and finally closed in 1933.

Brian went on to tell us of an earlier, larger and more radical strike, which is now less remembered. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the lumber industry was the backbone of the local economy. While the lumber barons lived in luxury, Brian explained that their workers did not. Long hours, (11 or 12 hour days, 6 days a week), for poor pay in a hazard-filled work place, where it was commonplace for workers to be maimed or killed, was the norm. As there was no work in the winter, there was no pay. Thus the winters were especially hard on the families already suffering from inadequate housing, poor diet, lack of sanitation and multiple diseases.

In 1891 there was a drop in demand for lumber and a corresponding drop in price. In response, in September, the mill owners, acting collectively, cut worker wages by 50 cents a week, almost a 20% pay cut and refused to honour an earlier promise to reduce the work day to 10 hours. The mill workers were not unionized, though an American-based union, the Knights of Labour, did have some membership in Canada, including 6 members at the Perley & Pattee Lumber Company. On the 14th of September the workers there demanded the reinstatement of their full wages, the mill owner, George Pattee, refused, insisting that he was only following what was being done at all the other mills in the area. The workers walked off the job, an illegal strike as 6 months notice was required. As such, the Knights of Labour did not support the action, preferring arbitration to confrontation. Representatives of the workers soon went to all the other mills and lumber yards, where these workers too put down their tools and joined the strike.

Brian pointed out that the mill owners were powerful. E. B. Eddy, who was also the Mayor of Hull, arranged, on the 16th, to have two companies of the Governor General’s Foot Guards and two companies of the 43rd Battalion called out, armed with live ammunition, to protect the mills. The troops were sent home the next day when workers representatives, among them Napoléon Fateux and J. W. Patterson, convinced Eddy that no damage would be done and established worker teams to safeguard the mills. The owners also tried to break the strike through the use of scab labour, but the strikers blockaded the roads, dissuading the scab workers from reporting.

Brian explained that the call for the 10 hour work day had a broad appeal across the working poor. The 2,500 mill workers were eventually joined by an additional 1,500 workers from other industries, a large block of the workforce at that time. Significantly, however, the more professional workers who had already achieved a reduced work week were generally not supportive. Support for the strikers, in terms of donations of funding and food, and even the creation of striker’s stores to help the families followed, but as time went on the momentum began to fade and the approach of winter caused cracks to develop on both sides of the dispute.

By mid-October, Brian explained, most workers had returned to their jobs, the mill owners having made no concessions. Approximately 1,000 experienced mill workers had left the area during the strike, 600 of those to Michigan. This delayed the return of the industry to full capacity. Shortly after the return to work the mill owners reversed the 50 cent pay cut and several years later a 10 hour work day was implemented.

The Historical Society of Ottawa has another article on the 1891 strike that can be read at: Strike! En Grève! Plus, you can read about more labour strife at the E.B. Eddy plant in the story: The Eddy Lock-out.

Brian pointed out that although both labour actions were ultimately unsuccessful, as a society we now only remember and honour the actions by the women match workers. This can be seen through the naming of a Gatineau library branch for Donalda Charron, the renaming of Boulevard de l’Outaouais, in the Hull section of Gatineau, as Boulevard des Allumettières and by an event organized by the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) in October 2014 as part of Women’s History Month. There has been no such recognition of the much larger strike of 1891. Perhaps it has simply been forgotten, though Brian speculates that it has more likely been intentionally ignored. No government or organized labour union of today would benefit from honouring a broad-based labour revolt that was led by workers themselves and not by professional leadership.