Ottawa’s Early Baseball History

We filled the virtual bleachers on the evening of Wednesday, April 9th, 2025 as we watched Steve Rennie start for the Historical Society of Ottawa. Steve is a baseball writer and researcher who lives in Ottawa. A former journalist, he is the president of the Ottawa-Gatineau and Eastern Ontario chapter of the Society for American Baseball Research (SABR). In the spring of 2024, he presented on Ottawa’s early baseball history at the Frederick Ivor-Campbell 19th Century Base Ball Conference in Cooperstown, New York. He has a particular interest in 19th century baseball in Canada and enjoys unearthing long-forgotten games and teams. He is a contributor and co-editor of “From Bytown to the Big Leagues: 150 Years of America’s Pastime in Canada’s Capital: Ottawa Baseball from 1865 to 2025” available online and his upcoming work will cover early baseball history in the far north and during the Klondike Gold Rush.

Steve began his session with a brief introduction to the origins of the sport. Although it has been widely claimed that Abner Doubleday invented baseball in 1839 in Cooperstown, New York, this myth has been debunked by baseball historians, the Doubleday family not living in Cooperstown at that time. The game had clearly existed earlier. It had made its way to Canada by 1838, the first recorded game being played in Beachville, Ontario. The Knickerbocker Base Ball Club of New York formalized a set of rules in the 1840s that were widely adopted and form the basis of today’s rules. Steve highlighted some of the differences, pitching being underhand, the batter being able to accept as many pitches as he liked as long as he didn’t swing and an out being recorded if the ball was caught on the first bounce. He pointed out that early on there were no gloves, catcher’s masks, or other protective equipment.

By the 1850s, Steve explained, Base Ball had become very popular, especially in the New York metropolitan area and was spreading following the rail lines. International play began as early as 1860 when a game was played by a team from Buffalo against a team from Hamilton, while another was played a few weeks later by teams from Ogdensburg and Prescott. Steve showed us that the Prescott team was identified in the newspaper as Greenville, but he suspects that it could have actually been Grenville, as in Leeds and Grenville. In 1869, the Cincinnati Red Stockings became the first fully professional Base Ball team, leading in 1871 to the establishment of the National Association of Professional Base Ball Players.

Steve told us that the first game he has so far been able to find in the Ottawa area took place in Metcalfe on September 13, 1865. An interesting aspect of the write-up of this event is that there was no description of the play, indicating that the readers must have been familiar with the game and that it must have been played locally for some time.

In 1867 Ottawa’s first Base Ball Club was formed, the New Dominion Club of Ottawa, likely taking its name from Confederation. They established a Club House at the Ottawa Skating and Curling Club on Albert Street and played in a field behind it. Shortly after their formation they travelled to Ogdensburg for a game, which they lost 141 – 20. Scores of this type were not uncommon in the early days due to the differences in pitching, rules and the relative experience of the players. The next year saw increasing interest in the game, the New Dominion Club often splitting into two teams to play themselves. They also played a team of mechanics, a 4 game set against a local cricket club, in which 2 games were Base Ball and 2 were cricket. There were 2 more games against the team from Ogdensburg, losing both but doing well in the first of thee two matches. There was a strong social element in the sport at this time, the games being followed by dinners, drinks and songs. In 1869, or just after, their club house and the field on which they played was subdivided into lots and sold, bringing an end to the New Dominion Club of Ottawa.

In 1871 a new club was formed, the Ottawa Base Ball Club, which included a number of members of the earlier New Dominion Club. Steve explained that they were responsible for creating the first Ball Park in Ottawa, actually in Stewarton, a separate village. The park was in the Gladstone/Cartier area to the canal and was needed to host a game on August 27, 1872 against the Boston Red Stockings, the most famous team in the world at that time. The Red Stockings returned to play a second game in 1873, Ottawa losing both games.

Steve gave us a bit of information about two of the early stars that are associated with Ottawa. George Latham, an American born player, played for the Ottawa Base Ball Club against the Red Stockings in the 1873 game. He joined the Red Stockings briefly in 1875 before moving on to play for a number of other teams. Jack Humphries was born in North Gower and was the first locally born player to go to play in the Major Leagues, serving as a backup catcher for a couple of teams.

Although Base Ball was very popular in Ottawa during the 1880s and 1890s, all the teams were amateur. Teams based around professions, government departments, or other local towns competed against each other. In the summer of 1898, Steve explained, the Ottawa Citizen started a campaign to bring professional Base Ball to Ottawa. The timing was good as the Rochester team of the Eastern League was in financial difficulty and so in mid-July it relocated to Ottawa. Met with initial excitement, the attraction faded as the team struggled to a losing season, and continued to lose money, an estimated $4,000 in just its 6-week stay in Ottawa. The team, known as the Senators, as was the team in Washington, folded at the end of the season. It was some years before Ottawa had another professional Base Ball team. July 19, 1898: Jimmy ‘Gussie’ Gannon leads Ottawa to its first home victory in professional baseball – Society for American Baseball Research

You can view Steve’s full presentation at: Ottawa’s Early Baseball History - The Historical Society of Ottawa

Steve also produced a pamphlet for us which has even more information and can be found on our website at: 127. Forgotten Gems: Ottawa’s Early Baseball History (1865–1900)

Ottawa’s Early Baseball History

Steve Rennie, author of “Forgotten Gems: Ottawa’s Early Baseball History” and “From Bytown to the Big Leagues: 150 Years of America’s Pastime in Canada’s Capital” recounts the early history of baseball in Ottawa.

I Want to Ride My Bicycle: How Ottawa Took on the Bicycle Craze

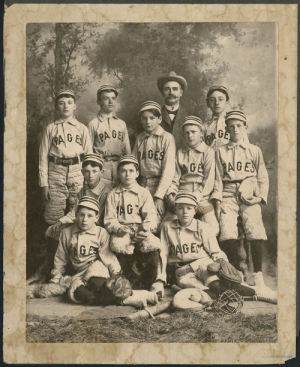

While not entirely present in this photograph, according to the by-laws of the same year, the club’s uniform consisted of a “Peaked Cap, Tunic, Knickerbockers, and Ribbed Stockings all of a Dark Blue Color. [with] the trimmings to be of Black Braid…”

The bicycle, in its various forms, became an established form of amusement in the 1860s. [[1]] It was however, not until the late 1890s, that the bicycle craze was in full swing. It was during this time that the bicycle became the site of much public discussion. For Ottawa, the craze had taken hold by April of 1895, with The Ottawa Journal declaring the Capital, “all hot for wheels.” [[2]] In the same year, according to the Ottawa business directory, a concentration of bicycle shops could be found on Bank and Sparks Streets, six on Sparks and two on Bank. [[3]] One of these shops was McFarlane Bros, located at 115 Bank Street, it was originally an iron foundry that took up bicycle manufacturing during this period.

This bicycle boom reflects Victorian ideals and preoccupations, namely that of health and respectability. At a time when there was a growing concern over cities being unhealthy spaces, bicycling was seen as the right kind of sport for the health of the nation, as it benefited both physical and moral health. Regarding morality, the perspective at the time concerning morality and sport, viewed amateur sports as pure, reflecting respectability, while professional sports, where money was earned, as corrupt. In examining the Ottawa Bicycle Club (established in 1882), this attitude regarding the bicycle comes into view, as the clubs’ mandate which stated that the club was only open to amateurs.

The stated objective of the Ottawa Bicycle Club, according to the by-laws from 1890, was “to promote the general interest of cycling and to encourage and facilitate “touring.’” [[4]] By the last decade of the 19 th century, there was a growing concern for the proper use of bicycles in public spaces in an era of the ‘safe bicycle.’ This era meant, not only changes to the bicycle itself but concerns for the activity of cycling. The club, and other clubs like it, engaged in family-oriented bicycling, whereby rowdy, reckless cycling (read masculine qualities) was viewed as improper. Before this, during the highwheeler (a bicycle with a large front wheel and a small back one) phase, clubs operated on a more informal basis. Members would engage in Victorian chivalry, taking on the role of ‘two-wheeled knights.’ [[5]] In highlighting ‘touring,’ the mandate of the Ottawa Bicycle Club heeded this concern for proper bicycling etiquette. Etiquette was reflected in the respectability of the club members and through maintaining proper order in public spaces. The activity of touring indicates a level of activity that was seen as being beneficial to one’s physical health while maintaining respectability.

Maintaining one’s respectability was especially important for women who, with the development of the safe bicycle, took up cycling. Admittance of women into the club likely occurred around the time that the above photograph was taken, as between 1890-1891 greater numbers of women actively took up cycling in Canada. By the late 1890s, women accounted for between one-quarter and one-third of all riders. [[6]] In addition to the Ottawa Bicycle Club opening its door to women, other ladies’ clubs within the Capital also took up learning to ride bicycles. [[7]] As The Ottawa Journal stated in 1896, “…it is no uncommon thing to see a number of women on bicycles riding along our roads.” [[8]]

Mrs. Albert H. Campbell on Wheel (1897) - James Ballantyne / Library and Archives Canada / PA-130015.

Mrs. Albert H. Campbell on Wheel (1897) - James Ballantyne / Library and Archives Canada / PA-130015.

Unlike previous iterations, the safety bicycle did not pre-empt women from the activity of cycling. This was in part because Victorian Women’s dress codes, which had made it possible to ride, could be accommodated, even creating new fashions directly linked to the leisure activity. The creation of a skirt, designed to meet “every requirement of the wheelwoman,” was the subject of an article from the February 12, 1897, issue of The Ottawa Citizen , which describes the skirt as seeming to “answer every requirement of modesty as well as convenience.” [[9]] Divided in the front and back to accommodate the frame of the bicycle, the skirt concealed the movement of limbs, while at the same time affording freedom. Women taking up cycling was, as with many other things where women entered the public sphere, not without objection. Those involved in reform, for example, expressed concern that it facilitated inappropriate relations between men and women. An article from the Dominion Medical Monthly and Ontario Medical Journal states that some objection to female cyclists was “…because it is injurious to the rider herself and decidedly immoral in its tendencies.” In response to the article, both cycling organizations and publications wrote to the editor to dispute the article’s claims regarding the question of women riders. [[10]] Women who rode became a ‘flaneur[use] on wheels,’ displaying good taste, appropriate attire, commitment to healthy motherhood, and bourgeois propriety in public while touring. [[11]] In addition to touring, women, as well as children, took part in public bicycle tournaments or “bicycle gymkhana” (something originally associated with equestrian skill) which had gained popularity at the time.

These tournaments brought together all the ideals of the safety bicycle era as it “favoured bicycling decorum and propriety over athleticism, though many of the events of the gymkhana required significant bicycle-handling skill.” [[12]] These events also signified the proper use of public space, usually taking place in and around a park, which was a cultivated and clean space. Taking place largely during the summer season, the gymkhana events involved such things as a bicycle parade and bicycle decoration, as well as games including obstacle races. While Ottawa held its own gymkhana as the bicycle craze was drawing to a close in 1900, it did so in what seems to be a uniquely Ottawan fashion, with the gymkhana taking place in the middle of November at the indoor Rideau rink. Jointly organized as a benefit by the lady’s auxiliaries of St Luke’s and the children’s hospitals, the program included races and drills, as well as a military musical ride. While the event was said not to have gotten as many spectators on its second night, it was said to be a success. [[13]] If low attendance was thought to be a sign of decreased interest in bicycling, ‘the number of shops related to bicycles suggests otherwise, as there were over 10 in business in 1900. [[14]]

Whether out for a leisurely tour or participating in an organized event, the bicycle boom certainly did not go unnoticed in the Capital. In taking up the sport of bicycling, Ottawa residents heeded the call that it was indeed the right kind of sport for the health of the nation. While the actual craze only lasted until around the turn of the century, the interest in cycling has remained a part of the capital’s landscape, enjoyed by many no matter the season.

Kirsten Widdes is currently an independent researcher and writer. She holds an MA in History from Carleton University, as well as a BEd in Junior/Intermediate Education from the University of Ottawa. She has been a volunteer with the Historical Society of Ottawa since August 2023 and currently serves as the managing editor of HSO blog.

[[2]]“All Hot For Wheels: The Spread of Bicycle Craze in the Capital,” The Ottawa Journal, April 4, 1895, 3, https://www.newspapers.com/image/43441283.

[[3]]Might Directory Co., Ltd, Classified business directory of the cities of Hamilton, London, Montreal, Ottawa and Toronto (Toronto: Might directory co., ltd, 1895), 280, https://digitalarchiveontario.ca/objects/355512/classified-business-directory-of-the-cities-of-hamilton-lon?ctx=5f968c77a9bdefd1d0331b218963f702e2154d97&idx=13.

[[4]]Ottawa Bicycle Club, Constitution and by-laws of the Ottawa Bicycle Club (Ottawa: A. Bureau & Freres Printers, 1890), 1, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.11587.

[[5]]Philip Gordon Mackintosh, “A Bourgeois Geography of Domestic Bicycling: Using Public Space Responsibly in Toronto and Niagara-on-the-Lake, 1890–1900,” Journal of Historical Geography20, 1 (2007): 139, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6443.2007.00303; G. B. Norcliffe, The Ride to Modernity: The Bicycle in Canada, 1869-1900 (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001), 195-196.

[[8]] “Women on Bicycles,” The Ottawa Journal, February 8, 1896,1,https://www.newspapers.com/image/43359474.

[[9]]“A New Bicycle Skirt,” The Ottawa Citizen, February 12, 1897, 3, https://books.google.ca/books?id=RmcuAAAAIBAJ&lpg=PA2&dq=bicycle%20skirt&pg=PA2#v=onepage&q=bicycle%20skirt&f=false.

[[10]]Rebecca Beausaert, “‘Young Rovers’ and ‘Dazzling Lady Meteors:’ Gender and Bicycle Club Culture in Turn-of-the-Century Small-Town Ontario,” Scientia Canadensis 36, no. 1 (2013): 34, https://doi.org/10.7202/1025788ar; “Female cyclists,” Dominion Medical Monthly and Ontario Medical Journal Vol.7, no.3 (September 1896): 255, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06539_15; Female cyclists,” Dominion Medical Monthly and Ontario Medical Journal Vol.7, no.5 (November 1896): 514, https://www.canadiana.ca/view/oocihm.8_06539_17.

[[11]] Norcliffe, The Ride to Modernity,244 -245; Mackintosh, “A Bourgeois Geography of Domestic Bicycling, 133.

[[12]]Mackintosh, “A Bourgeois Geography of Domestic Bicycling, 144. A Faneuse or Flaneur is some who strolls about the city, taking in its sights and sounds.

[[13]]“Society and personal,” The Ottawa Citizen, November 13, 1900, 9, https://books.google.ca/books?id=elguAAAAIBAJ&lpg=PA5&dq=%22Bicycle%20gymkhana%22&pg=PA5#v=onepage&q=%22Bicycle%22&f=false; “A Bicycle Gymkhana,” The Ottawa Journal, October 3, 1900, 8, https://www.newspapers.com/image/42370524/; “The Gymkhana,” The Ottawa Journal, November 18, 1900, https://www.newspapers.com/image/42371912/.

Beep Ball, Disability, and Sports Memory in Ottawa

David (Dave) Kent - Beep Ball, Disability, and Sports Memory in Ottawa

In March 2024, the Historical Society of Ottawa sat down with David (Dave) Kent to discuss beep ball, disability and sports memory in Ottawa.

Why don’t we start by telling a bit about yourself and your life?

Dave: Well I was born in Ottawa in the summer of 1951 and did almost all of my schooling, elementary, middle and high school in Ottawa. I went to the University of Ottawa in the early '70s and did an arts degree in Geography. I then went to the University of Manitoba to take a course in data processing, or what they call computer science now. I had normal vision until I was about 8 or 9, when I lost 90% of my sight.

And what was it like attending public school with a visual impairment?

Dave: In the 1960s, it was normal for any kid with any difference to be sent off somewhere, like the Ontario School for the Blind in Brantford or similar schools for deaf children. There were also sunshine classes for the kids in wheelchairs. My parents wanted me to stay in the public school system in Ottawa because they knew I’d have to adjust to this anyways. But there were no organized supports, it often depended on what the teacher thought they could do to help. Sometimes my teacher might copy a test from the blackboard onto paper for me or use the sideboard instead.

The program I took at the University of Manitoba was supported by the CNIB (Canadian National Institute for the Blind) and the governments. I think it was called Data Processing for the Blind. The reason I took the course, even though I already had a Bachelor's degree from the University of Ottawa, there weren’t any jobs at the time. So I now worked 35 years in what became information technology, 7 years for the Federal Government and 28 years for the City of Ottawa in their IT team, designing programs and databases. In about 1980, I met my wife. We’ve been together 40 years now and have six kids. We also have a cat named Tintin. So that’s the 5 minute biography.

So can you explain to me what exactly beep ball is and how you became involved? I think I have an idea from my Google searches but I’m not sure.

Dave: So beep ball or beeping baseball has its origins in the US, probably in the early '60s. The culture in the US was that there was really only one sport: baseball. The NFL, NHL, and the NBA were just fledgling organizations. The only real sport was baseball, “America’s game” or “America’s pastime.”

There was a group of former Bell telephone employees called the Bell Pioneers, and they believed every boy in America should be able to play baseball. So they created a baseball the size of a softball with a pin, and inside there’s a device that beeps. When you pull the pin out it starts beeping, and when you put it back in it stops.

In the US, it’s played by someone throwing the ball in the air to a blind batter, hitting it, and then running to a beeping base. That isn’t quite the way we played. We played the more traditional version where the batter would be blindfolded, with six fielders, also blindfolded, but the pitcher and the catcher were sighted. The pitcher would pull the pin to make the ball beep, he or she would say “ball coming” and then roll the ball across the ground. The batter would be kneeling, and sweep their bat across the ground to hit the ball.

The batter would start running towards first base with the assistance of a guide. In the field, when the ball was caught, that ended the play. If the batter made it to the base, they were safe. If they were caught between bases, they were out. Beep ball was also played on grass rather than a baseball surface because quite often, you’re on your hands and knees crawling around and such. In 1992, Maclean-Hunter, a Canadian cable company, actually did a ten minute video for us, so we have that on VHS.

How I became involved was that my wife's father was actually working for CNIB in 1986. At the time, CNIB was trying to put together a summer activity program for their client base. They had a fellow called Murray Thorpe, and he decided to start a beep ball league for the clients with the idea that it promotes physical and social activity. There was a real concern amongst the blind community about physical activity, and of course, blindness can be socially isolating.

So that’s how I first got involved.

How often did you play?

Dave: We used to play on a weekly basis. At the time, there was actually a beep ball tournament in Belleville, and we ended up winning the first couple of years.

After that first summer, the group of us who met one another through beep ball continued to play for the next few years. In 1990, Ottawa was part of the Twinning Games, which involved an exchange of athletes between Ottawa and The Hague. The people from The Hague came here and we wrote to the City of Ottawa saying we’d be interested in meeting some of their blind athletes. A group came over who played Showdown, a game very much like air hockey. If you saw it and didn’t know what it was, you’d think they were just playing air hockey. So it worked out really well because both cities were worried about finding a group on either side who could accommodate their needs.

In 1991, Ken McColm was walking across the country. He was a blind fellow walking across Canada for diabetes because that’s how he had lost his sight. When he got to Ottawa, I got in touch with the Diabetes Association and we put together a beep ball exhibition game against the CJOH NoStars on the main lawn of Parliament Hill. The Diabetes association then asked if we’d be interested in running a tournament next year. This was at a time when Hope Volleyball was really big, so we wanted to create a beep ball tournament. In 1992, we had B.A.T., the Blind Awareness Tournament on Parliament Hill with four teams. In 1993 we had eight teams. In '94 it was 16 teams and we moved to St. Paul’s University. We then got too big for people to run this part-time, so that was the last of the B.A.T. tournaments, but we continued to play after that.

In the city at the time there was a blind sports club called the Capital Eyes, so we used that pun. As the Capital Eyes we were part of the Ottawa disabled sports club, we even had our own shirts!

What other activities did you participate in? Did you engage in politics at all?

Dave: Apart from our normal play, we used it for reverse integration, so we’d take the equipment to schools, guide meetings, and offices to play with sighted folks. This really was reverse integration and it gave those people a chance to see what it would be like to not see or have to rely on other people.

We didn’t do any political lobbying, we were more recreational. But we did have various people come out to see us, like the head of Baseball Canada. We wanted them to know that, hey, we’re out here too and we’re playing too. He had never heard of beep ball, he was fascinated. During one of our tournaments we also commissioned the Dominion Carillon player Gordon Slater to play Take Me Out to the Ball Game on the Peace Tower Carillon.

Throughout your career, have you seen any changes in the way people discuss disability?

Dave: There was certainly a change in attitude between elementary school and high school, and when I got to university. When I went to university, the only thing people cared about was if you could do the work.

When I first entered the workforce there was a reluctance or a concern about hiring an individual who was blind. They were concerned about if you could do the job, so you had to prove you could do it before their concerns were alleviated. I found the people I was working with very supportive. But if you interviewed with people in other organizations, the first thing they’d realize was that this guy has a problem, and did they really want to invite a problem into their workplace. So I suspect I may not have gotten some jobs over my life because of their lack of vision, not my lack of vision.

There were no accommodations when I entered the workforce in 1975, everything was print based, so at one point I did have a manual sent off the CNIB to enlarge it. But really no special accommodations. I’ve now been out of the workforce for 13 or 14 years so I can’t really talk about the present day. Certainly technology has changed a lot. There's a lot of accessibility features built into devices that didn’t exist most of the time I was working.

Listen to Dave explain the origins of beep ball and how it's played in Ottawa.

And, in this linked video, Dave shows us what a beep ball looks and sounds like.

Learn the Beep Ball - Rules of Play.

Further Reading and Resources:

- About the CNIB: https://www.cnib.ca/en?region=on

- About the Bell Pioneers: http://www.telecompioneers.ca/pioneer-links/bellaliant

- Get involved with Ottawa’s Miracle League: https://www.miracleleagueofottawa.com

- About Diabetes Canada: https://guidelines.diabetes.ca/about

-

About Hope Volleyball Ottawa: https://hopehelps.com

Women on Ice: Ottawa’s Own

It was just coincidental, though perhaps entirely appropriate, that the presentation on March 23, 2024, at the Main branch of the Ottawa Public Library titled “Ottawa Women on Ice” took place against the backdrop of the World Figure Skating Championships in Montreal and a game between Ottawa and Toronto in the newly-formed Professional Women’s hockey League. James Powell, the speaker that afternoon, told an enthusiastic audience of 44 about Ottawa’s lengthy and often glorious history in women’s hockey and the achievements of two Ottawa women in figure skating—Barbara Ann Scott and Elizabeth Manley. James is a frequent speaker at HSO and community events; runs the blog “Today in Ottawa’s History” and was awarded the Historical Society of Ottawa’s Story Teller award in 2023 for his fine work in telling Ottawa’s history.

Few probably realize that women’s hockey started in Ottawa when Isobel Stanley, the daughter of Lord Stanley, Canada’s Governor General from 1888-1893, strapped on a pair of skates in 1889 and stick-handled around other Rideau Hall women in the first ever women’s hockey game in an outdoor rink at Government House. That same year, Isobel Stanley and other ladies from Rideau Hall triumphed over a team from the Rideau Rink in the first ever women’s hockey game covered by the press. With a vice-regal stamp of respectability helping to alleviate concerns about the appropriateness of women playing hockey, women’s hockey teams multiplied in the Ottawa-Hull area and throughout the Ottawa Valley, this included the “Alphas” of New Edinburgh, the Rideau Rink Ladies, the Vestas of Hull, and the Cliffside Ladies, also known as the “Busy Bees,” who claimed the first city championship when they defeated the Sandy Hill Ladies in 1908. Away games by Ottawa teams to play teams in Smiths Falls and Cornwall were chaperoned to keep the young ladies in line. Long skirts and tam-o-shanters were the uniforms of the day.

Women’s hockey received a major boost with the outbreak of World War I. With the men away, scarce rink time opened up for women. As well, rink owners looked for new ways to rent out the ice and fill seats. In Montreal, a women’s hockey league brought in thousands of fans attracted by the high calibre of the game. Many also came to see the Cornwall Victorias, led by their superstar Albertine Lapensée, also known as the “Miracle Maid” and “Étoile des étoiles”, and the Ottawa Alerts, the formidable team from the Capital. Lapensée was likely the first professional female hockey player.

The origins of the Ottawa Alerts are obscure but the team, captained by Edith Anderson burst onto the scene in 1916. Their most fierce local rivals were the Westboro Pats led by Tena Turner. The two teams fought for the city championship in 1917 with the Alerts prevailing in a two-game, total goal series. The Alerts then defeated the Westerns, Montreal’s hockey champions, to win the Dey Cup.

The Ottawa Alerts joined the Ladies’ Ontario Hockey Association (LOHA) in 1922 when the league formed, bringing together fifteen teams from across the province. Behind their star player, the all-round athlete Shirley Moulds, the team won two consecutive championships in 1923 and 1924. The Alerts went into decline when Moulds moved to the Ottawa Rowing Club as the team’s captain. The “Scullers” defeated the Alerts to take the city championship in 1927, and subsequently won the provincial title, defeating the Toronto Pats.

The Great Depression was the death knell for women’s hockey in Ottawa and in Canada more generally. Both the Alerts and the Scullers disappeared into history as did the LOHA and the Dominion Women’s Amateur Hockey Association, the latter founded in 1933. By the onset of World War II, organized women’s hockey was no more. However, before the end came, the 1930s saw the emergence of the most powerful women’s hockey team of the era—the Preston Rivulettes. During its short career, the team lost only two out of 350 games.

Women’s hockey didn’t re-emerge as a significant sport until the 1970s. However, leading the way in the post-war era was ten-year old Dee Dee Hamilton who stepped into the breach in 1956 when the goalie on her brother’s team, the St. Pat’s, couldn’t play in a game hosted by Ottawa’s Cradle Hockey League. So good was Dee Dee that she played in the 1957 All-Star Game. For two years, she was the only girl amidst 800 boys in the league.

With the establishment of a new professional women’s hockey league at the beginning of 2024 with a team in Ottawa, it is possible that the old “Alerts” name may be revived. In the lead-up to the formation of the league, a number of trademarks were registered for potential names of its clubs. In addition to such monikers as the Toronto Torch and the Montreal Echo was the Ottawa Alert.

Credit: Frank Royal / National Film Board of Canada / Library and Archives Canada / PA-112691.Switching to figure skating, James traced the career of Canada’s sweetheart, Barbara Ann Scott, from winning the Canadian Junior Figure Skating crown in 1940 to taking the gold medal at the 1948 Winter Olympics held in St. Moritz, France. But it didn’t come easily for Scott. Her success required long hours of practice and hard work, training at the Minto Skating Club, the skating club founded by Lord and Lady Minto in 1903. James showed a short film of her performance at St Moritz which displayed her grace and form as a gold-medal figure skater.

Credit: Frank Royal / National Film Board of Canada / Library and Archives Canada / PA-112691.Switching to figure skating, James traced the career of Canada’s sweetheart, Barbara Ann Scott, from winning the Canadian Junior Figure Skating crown in 1940 to taking the gold medal at the 1948 Winter Olympics held in St. Moritz, France. But it didn’t come easily for Scott. Her success required long hours of practice and hard work, training at the Minto Skating Club, the skating club founded by Lord and Lady Minto in 1903. James showed a short film of her performance at St Moritz which displayed her grace and form as a gold-medal figure skater.

Returning to Ottawa as a national hero after the Olympics, some 70,000 fans met her train at Union Station, where she was personally greeted by Prime Minister Mackenzie King and Ottawa Mayor Stanley Lewis. Schoolchildren were given a half-day holiday. In honour of her victory, Ottawa gave Scott a car with the licence plate 48-U-1. She then started her professional career, ousting Sonja Henning, her arch rival, from the Hollywood Ice Review. In 1950, the most desired Christmas gift was a Barbara Ann Scott doll, complete with white figure skates, costing a steep $5.95.

Scott retired from skating in 1955 when she married Tom King. In 1991, she was appointed to the Order of Canada. Scott passed away in 2012 in Florida at age 84. She bequeathed her sports memorabilia to the City of Ottawa.

James ended his presentation with the career of another daughter of Ottawa, Elizabeth Manley, who won the silver medal at the 1988 Olympics in Calgary. Like Scott forty years earlier, it took years of grit and determination to achieve perfection—and that was what she achieved in her long program in Calgary. Although she came first in that section of the competition, she lost overall by a hair to East Germany’s, Katerina Witt. At the end of a short video of her long program, people in the library auditorium broke out into applause, indicative of the power of Manley’s performance thirty-four years ago. Manley was appointed to the Order of Canada in 1988, and, following her skating career, has devoted considerable time to charity.

In the usual question and answer section that followed, three descendants of Shirley Moulds, the Ottawa Alerts’ star player, identified themselves in the audience. They indicated Moulds had been a very private person who had not talked about her hockey career. Her niece said that it was only after Shirley’s death that she became aware of her prowess as a hockey player. The only thing she knew was that Aunt Shirley was a great bowler! Shirley Moulds’ great-nephew was instrumental in Moulds being named to Ottawa’s Sports Hall of Fame in 2010.

Sports Vignettes from Old Ottawa

Football fans in this town have managed to remain loyal to their home team for 145 years, be it the Rough Riders, or the Renegades, or back again to the Rough Riders, and now the Redblacks. Hockey fans have retained their allegiance to two different Senators teams over 80 seasons, separated a by a 58-year winter when locals were forced to chose between the Leafs, Habs, or other members of the Original Six. But as we learned at our January 26th presentation, Ottawa’s sports history is much more than hockey and football.

Our guest speaker for the January 26, 2022, Virtual Speaker Series was HSO member James Powell, who began his presentation by reminding us that in the late 19th century, watching professional sports was not nearly as popular as participating in amateur pastimes like lacrosse, cricket, and cycling. As James noted, skiing was a popular pastime in Ottawa before devotees could even come to agreement on how to spell the name of their favourite sport.

As always, when it comes to James’ presentations, his history is well researched. During the Q&A session that followed, one participant though he might have stumped James with a question regarding the obscure sport of “hose reel racing” which was held annually in Ottawa a century ago. Suffice to say, James had an answer. I won’t tell you here what hose reel racing is. You’ll find it more entertaining to watch James’ presentation for the answer.

Like all our Virtual Speaker Series presentations, you can find James’ talk at our HSO website. The website is also the place to register for upcoming presentations.

Lord Stanley’s Cup

18 March 1892

Each spring as winter’s snows begin to recede, the thoughts of Canadians turn to the Stanley Cup. One of the oldest sporting trophies in the world, the Cup is the symbol of hockey supremacy in North America. Its provenance is well known; it was purchased and given to the hockey community by Lord Stanley of Preston, Canada’s Governor General, in 1892. What is less well known is that Ottawa featured prominently in the Cup’s story. It was in Ottawa that Stanley let it be known his intention to provide a championship trophy. As well, during his vice-regal tenure in the nation’s capital, the Governor General, an avid hockey fan, and his equally hockey-mad children, did much to make hockey Canada’s national game. The Ottawa Hockey Club also played in the first Stanley Cup championship game.

The sport of ice hockey has a long history. It probably originated in “ball and stick” games played by both Europeans and natives peoples in North America. Shinny, an early form of ice hockey, was played on rivers or ponds in Nova Scotia during the early nineteenth century. Shinny could involve scores of players on each team, using a wooden puck, one-piece hockey sticks and hockey skates. Modern ice hockey dates from early 1875 when Halifax native James Creighton organized an indoor game at the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal. Given the constrained skating surface, teams were limited to nine per side (reduced to seven in 1880). Played with a flat wooden disk using hockey sticks made by Mi’kmaq carvers from Nova Scotia, the game used “Halifax Rules” that included a prohibition on the puck leaving the ice and no shift changes. The match was an overwhelming success for both its participants and its appreciative audience.

In response to growing interest in the sport in central Canada, the Amateur Hockey Association of Canada (AHAC) was formed in 1886 with five teams, four from Montreal (the Victorias, the Crystals, the Montreal Hockey Club, and McGill College) and one from Ottawa, the Ottawa Hockey Club, known as the Ottawas. The Ottawas were established in 1883 and were a frequent participant in hockey games held during the Montreal Winter Carnival during the 1880s.

Lord Stanley of Preston arrived in Canada in 1888 to take up his position as the Dominion’s sixth Governor General. An avid sportsman, he was introduced to the game of ice hockey in February 1889 when he and members of his family, including his eldest son Edward and daughter Isobel, visited the Montreal Winter Carnival. Arriving while a hockey game was in progress—play was temporarily halted on his arrival—the Governor General, his family and friends watched the Montreal Victorias defeat the Montreal Hockey Club.

Lord Stanley was instantly hooked on the game. He quickly built an outdoor rink at Rideau Hall, his Ottawa residence, for the use of his family and staff. He took to the ice himself, though he apparently got into some trouble for skating on the Sabbath. In March 1889, his Rideau Hall rink was the site of what is believed to be the first woman’s hockey match between a Government House team on which Isobel Stanley played, and a Rideau ladies team. Her brothers, Edward, Arthur, Victor and Algernon, were also keen hockey players. They played with various official aides, MPs and senators on a team dubbed the “Rideau Rebels,” but more formally known as the Vice-Regal and Parliamentary Hockey Club. The Rebels played exhibition games throughout eastern Ontario including Kingston and Toronto that helped to popularize the game. The fact that Lord Stanley had placed his vice-regal stamp of approval on the game was another important factor in hockey’s rapid acceptance as Canada’s national winter sport.

In 1890, Lord Stanley’s son, Arthur, along with two team mates from the Rideau Rebels, helped create the Ontario Hockey Association (OHA), composed of thirteen teams from Toronto, Kingston and Ottawa, later joined by a team from Lindsay. Today, the OHA oversees junior hockey in Ontario. During the late nineteenth century, long before there was a National Hockey League and professional players, OHA teams represented the cream of Ontario hockey. The Ottawa Hockey Club team played in both the OHA and the AHAC centred in Montreal.

The Stanley Cup dates from 18 March 1892. That night, a celebratory dinner for members of the Ottawa Hockey Club was held at the Russell House Hotel. The Russell House was Ottawa’s top watering hole at the time, standing at the north-eastern corner of Sparks and Elgin Streets, roughly between today’s National War Memorial and the National Arts Centre. The Ottawas had just finished a championship year, winning the Cosby Cup of the OHA and holding the AHAC championship from January to early March before losing it to the Montreal Hockey Club. The Ottawa Evening Journal noted that the back of the dinner’s menu cards recorded the achievements of the team: nine championship matches won to only a single defeat, during which the team scored 53 goals “against the best teams in Canada,” allowing only 19 goals the other way.

Accounts differ on the number of people at the dinner. The Journal reported that there were between 70 and 80 present, while the Montreal Gazette said that about 200 admirers attended. The latter, larger number probably reflected the addition of the ladies who joined the men after the dinner for “ices.” Mr J.W. McRae, president of the Ottawa Amateur Athletic Association, the senior umbrella sporting association to which the Ottawa Hockey Club was affiliated, presided over the soirée, while the band of Governor General’s Foot Guards provided suitable musical entertainment.

At about 10pm, after the loyal toast to Queen Victoria, followed by another toast to the health of the Governor General, Lord Kilcoursie, an aide to Lord Stanley, rose to reply on behalf of the Governor General who had been unable to attend the evening’s event. After thanking the gathering, Kilcoursie read out a letter from Stanley. Dated 18 March 1892, it said:

I have for some time past been thinking that it would be a good thing if there were a challenge cup which should be held from year to year by the champion hockey team in the Dominion. There does not appear to be any such outward and visible sign of a championship at present, and considering the general interest which matches now elicit, and in the importance of having the game played fairly and under rules generally recognized, I am willing to give a cup, which shall be held from year to year by the winning team.

I am not quite certain that the present regulations governing the arrangement of matches give entire satisfaction, and it would be worth considering whether they could not be arranged so that each team would play once at home and once at the place where their opponents hail.

The letter was enthusiastically received by the partisan hockey crowd.

Kilcoursie also revealed that the Governor General had commissioned his former military secretary, Captain Charles Colville of the Grenadier Guards, who had recently returned to Britain, to purchase an appropriate trophy on Stanley’s behalf.

After a series of more toasts, including one to the Ottawa Hockey team as well as others to members of the league, the Press and the Ladies, the dinner broke up at about midnight, though not before many songs were sung. In particular, Lord Kilcoursie entertained the party goers by singing a “ditty” titled The Hockey Men that he had personally composed to honour the members of the Ottawa Hockey Club. The first two verses went:

There is a game called hockey

There is no finer game

For though some call it ‘knockey’

Yet we love it all the same.

This played in His Dominion

Well played both near and far

There’s only one opinion

How ’tis played in Ottawa.

At the end, the crowd gave “a rousing chorus, rendered in stentorian style” according to the Journal, repeating the third verse of the eighteen-verse poem:

Then give three cheers for Russell

The captain of the boys.

However tough the tussle

His position he enjoys.

And then for all the others

Let’s shout as loud we may

O-T-T-A-W-A!

Over in England, Captain Colville purchased Stanley’s Cup from the London silversmiths G.R. Collis of Regent Street for the sum of 10 guineas (ten pounds, ten shillings). As one pound was worth $4.8666 in Canadian money, this was the equivalent to $51.10, a considerable sum in 1892. On one side of the silver bowl with a gilt interior was engraved “Dominion Hockey Challenge Trophy,” while the inscription “From Stanley of Preston” with his family coat of arms was on the other. The Cup arrived in Ottawa the end of April 1893 and was entrusted to two trustees, Sheriff John Sweetland and Philip D. Ross.

The original Stanley Cup. The silver bowl stands 19cm high and has a diameter of 28.5 cm and a circumference of 89 cm

The original Stanley Cup. The silver bowl stands 19cm high and has a diameter of 28.5 cm and a circumference of 89 cm

Library and Archives CanadaThe trustees announced that the Cup would henceforth be called the “Stanley Cup” in honour of its donor and, as specified by Lord Stanley, it would be a “challenge” cup. In other words, the Cup would be open for all. Any team could challenge the holder of the Cup for the championship title though the two trustees had the final say on whether a challenge would be accepted. Other conditions included the requirements that a winning team keep the trophy “in good order,” that each winning team (except for the first winner) would engrave its name on a silver ring fixed to the trophy at its own cost, that the Cup was not the property of any one team, and that in case of doubt over who was rightly the champion team in the Dominion, the trustees’ decision was final.

Unfortunately, the presentation of the first Stanley Cup in May 1893 was mired in controversy. The Montreal Amateur Athletic Association (MAAA) was awarded the trophy by virtue of the 7-1 victory of its affiliated hockey team, the Montreal Hockey Club, over the Ottawa Hockey Club, the OHA champions. The trustees duly engraved Montreal AAA on the Cup, and arranged for Sheriff Sweetland to present the trophy at the Association’s Annual General Meeting. The president of the Montreal Hockey Club, James Stewart, who was also a player on the team, was asked to attend the Annual General Meeting to receive the Cup. However, Stewart refused to accept the trophy until the terms and conditions related to holding the Cup were clarified. Enraged by this decision, and not willing to embarrass the Governor General’s emissary, Stewart accepted the Cup from Sweetland on behalf of the MAAA.

The spat between the MAAA and the Montreal Hockey Club went on for some months. After a number of letters between the two organizations and between Sweetland and Ross, a reconciliation was achieved, and the Stanley Cup was finally transferred to the Montreal Hockey Club in time for the 1894 championship game. Held in late March of that year with the Ottawa Hockey Club, their long-time rivals, the match attracted some five thousand cheering fans to the Victoria Skating Rink in Montreal. After Ottawa took a one-goal lead, the Montreal team stormed back with three unanswered goals to win the game 3-1 and the Cup. Later, the neutral words “Montreal 1894” were engraved on the Cup to avoid any hard feelings between the parent Montreal Association and its related Montreal Hockey Club.

Sadly, Lord Stanley, the man behind the Cup, was not there to witness the first challenge match for his trophy. He had returned home the previous summer to take up the duties as the 16th Earl of Derby following the death of his elder brother.

Sources:

Batten, Jack, Hornby Lance, Johnson, George, Milton Steve, 2001. Quest for the Cup, A History of the Stanley Cup Finals 1893-2001, Jack Falla, Genera Editor, Thunder Bay Press: San Diego.

Hockey Hall Of Fame, 2016. Stanley Cup Journal.

Jenish, D’Arcy, 1992. The Stanley Cup: A Hundred Years of Hockey At Its Best, McClelland & Stewart Inc.: Toronto.

McKinley, Michael. 2000. Putting A Roof On Winter, Greystone Books: Vancouver.

Montreal, Gazette (The), 1892. “Lord Stanley Promises To Give A Championship Cup,” 19 March.

Ottawa Evening Journal (The), 1892. “Stars of the Ice.” 19 March.

————————————, 1893. “The Stanley Cup.” 1 May.

Shea, Kevin & Wilson, John J., 2006. Lord Stanley: The Man Behind The Cup, Fenn Publishing Company Ltd: Bolton, Ontario.

Vaughan, Garth, 1999. The Birthplace of Hockey.

Wikipedia, 1891-92, 2014. Ottawa Hockey Club Season.

Images:

Lord Stanley of Preston, 1889. Topley Studio/Library and Archives Canada, PA-027166.

The Stanley Cup, Library and Archives Canada.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.