Solidarity in the Chaudière District

The Main Branch of the Ottawa Public Library welcomed us back on Saturday, September 28, a beautiful fall afternoon, for our first in-person English language Speaker Session of the 2024 / 2025 series. We were pleased to partner with the Workers History Museum for this presentation and honoured to have their President, David Dean, on hand to introduce our guest speaker. Brian McDougall describes himself as a “socialist historian”, one who asks different questions and so draws different conclusions than main-stream historians. David Dean described Brian as a former civil servant, educator, author and activist with a dedication to public history. Brian related the stories of two early strikes and how they are now remembered. His audience of 40 was enthralled.

Brian began by giving us some background on the match industry at the turn of the 20th century. Prior to the general electrification of the world, matches were a critical product and the E. B. Eddy factory in Hull was at one time the largest match making factory in the British Commonwealth. The work, which involved men cutting the matches and women making the packaging and packing the matches into the boxes, was not only low paying, as was all industrial work at that time, it was also highly dangerous. Prior to the First World War, matches were made using white phosphorous, a highly flammable and poisonous chemical which resulted in a condition called phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, (aka Phossy Jaw), in which the vapours from the white phosphorous destroyed the bones of the jaw. Fire was another ever-present danger.

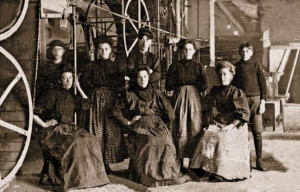

The ‘Match Girls’ (les Allumettières) were young, poorly educated, French, Catholic women, forced into the work force by the low wages paid to all members of the working class. Their living conditions were appalling, characterized by large families inadequately housed, with poor sanitation, bad nutrition and rampant disease. Working women held the dual responsibilities of contributing to the family income while also caring for all of its members.

Brian told us, perhaps surprising many, that the women match makers at E.B. Eddy were unionized: l'Union ouvrière féminine de Hull. The women, however, were not permitted to negotiate for themselves, this being done “on their behalf” by male union leaders and the Oblate Fathers, the church being central to all aspects of life in that community. The negotiators believed in a strategy of progress through cooperation and conciliation with the English ownership rather than a strategy of confrontation.

A heavy demand for matches, led the company, in October 1919, to demand that the women work double shifts. The women refused and were locked out. After some discussions with the male leadership, the company offered a shorter work week and an increase in wages, but demanded the right to change work hours as they wished and included a “yellow-dog” clause in the proposed settlement that would ban the women from union membership. The women refused. Shortly thereafter an agreement was reached in which the women would work double shifts for a period of 4 months, would receive a 50% pay increase (little in real terms) and would retain their union membership. This was accepted and work resumed.

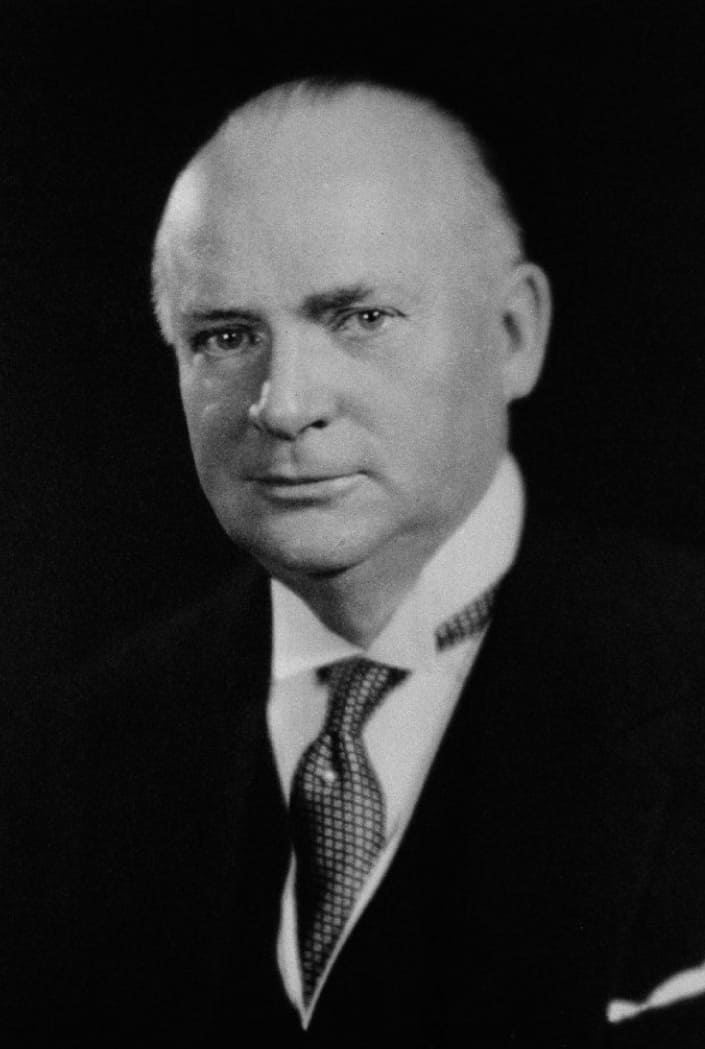

Richard Bedford Bennett, LAC 1930.Brian explained that labour issues came to a head again in September 1924, this time driven by a drop in prices for matches. By now the company had left the control of the Eddy family, with future Prime Minister R. B. Bennett being the principle owner, who held that he was not bound to agreements signed by the previous owner. The company demanded a 50% pay cut and to seize the hiring process from the women supervisors, with the intention to hire non-French Catholics and so break the union. In response, union president, Donalda Charron led the women out on strike. The women picketed, fundraised, held 9 public meetings to explain their position, and so received both financial support and donations of food from the local communities. This included printed support from the French language newspaper Le Droit.

Richard Bedford Bennett, LAC 1930.Brian explained that labour issues came to a head again in September 1924, this time driven by a drop in prices for matches. By now the company had left the control of the Eddy family, with future Prime Minister R. B. Bennett being the principle owner, who held that he was not bound to agreements signed by the previous owner. The company demanded a 50% pay cut and to seize the hiring process from the women supervisors, with the intention to hire non-French Catholics and so break the union. In response, union president, Donalda Charron led the women out on strike. The women picketed, fundraised, held 9 public meetings to explain their position, and so received both financial support and donations of food from the local communities. This included printed support from the French language newspaper Le Droit.

After two months the male negotiators and the company reached a settlement in which the women would return to work at their same hours and rate of pay. The union would remain in place. No improvements in working conditions were achieved. Donalda Charron was not rehired and the women supervisors lost control of the hiring process. The women supervisors were later fired and the union was lost.

The two strikes of 1919 and 1924 were the first by solely women workers in the Province of Quebec and in this area. The match works was sold in 1927 and finally closed in 1933.

Brian went on to tell us of an earlier, larger and more radical strike, which is now less remembered. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the lumber industry was the backbone of the local economy. While the lumber barons lived in luxury, Brian explained that their workers did not. Long hours, (11 or 12 hour days, 6 days a week), for poor pay in a hazard-filled work place, where it was commonplace for workers to be maimed or killed, was the norm. As there was no work in the winter, there was no pay. Thus the winters were especially hard on the families already suffering from inadequate housing, poor diet, lack of sanitation and multiple diseases.

In 1891 there was a drop in demand for lumber and a corresponding drop in price. In response, in September, the mill owners, acting collectively, cut worker wages by 50 cents a week, almost a 20% pay cut and refused to honour an earlier promise to reduce the work day to 10 hours. The mill workers were not unionized, though an American-based union, the Knights of Labour, did have some membership in Canada, including 6 members at the Perley & Pattee Lumber Company. On the 14th of September the workers there demanded the reinstatement of their full wages, the mill owner, George Pattee, refused, insisting that he was only following what was being done at all the other mills in the area. The workers walked off the job, an illegal strike as 6 months notice was required. As such, the Knights of Labour did not support the action, preferring arbitration to confrontation. Representatives of the workers soon went to all the other mills and lumber yards, where these workers too put down their tools and joined the strike.

Brian pointed out that the mill owners were powerful. E. B. Eddy, who was also the Mayor of Hull, arranged, on the 16th, to have two companies of the Governor General’s Foot Guards and two companies of the 43rd Battalion called out, armed with live ammunition, to protect the mills. The troops were sent home the next day when workers representatives, among them Napoléon Fateux and J. W. Patterson, convinced Eddy that no damage would be done and established worker teams to safeguard the mills. The owners also tried to break the strike through the use of scab labour, but the strikers blockaded the roads, dissuading the scab workers from reporting.

Brian explained that the call for the 10 hour work day had a broad appeal across the working poor. The 2,500 mill workers were eventually joined by an additional 1,500 workers from other industries, a large block of the workforce at that time. Significantly, however, the more professional workers who had already achieved a reduced work week were generally not supportive. Support for the strikers, in terms of donations of funding and food, and even the creation of striker’s stores to help the families followed, but as time went on the momentum began to fade and the approach of winter caused cracks to develop on both sides of the dispute.

By mid-October, Brian explained, most workers had returned to their jobs, the mill owners having made no concessions. Approximately 1,000 experienced mill workers had left the area during the strike, 600 of those to Michigan. This delayed the return of the industry to full capacity. Shortly after the return to work the mill owners reversed the 50 cent pay cut and several years later a 10 hour work day was implemented.

The Historical Society of Ottawa has another article on the 1891 strike that can be read at: Strike! En Grève! Plus, you can read about more labour strife at the E.B. Eddy plant in the story: The Eddy Lock-out.

Brian pointed out that although both labour actions were ultimately unsuccessful, as a society we now only remember and honour the actions by the women match workers. This can be seen through the naming of a Gatineau library branch for Donalda Charron, the renaming of Boulevard de l’Outaouais, in the Hull section of Gatineau, as Boulevard des Allumettières and by an event organized by the Public Service Alliance of Canada (PSAC) in October 2014 as part of Women’s History Month. There has been no such recognition of the much larger strike of 1891. Perhaps it has simply been forgotten, though Brian speculates that it has more likely been intentionally ignored. No government or organized labour union of today would benefit from honouring a broad-based labour revolt that was led by workers themselves and not by professional leadership.

The Anishinabek

Time immemorial and 7 October 1763

Canada is widely viewed as a young country, its history stretching back no more than a few hundred years to the arrival of French and British settlers to its shores. But this is a very blinkered view of things. The territory that we now call Canada was not terra nullius when the Europeans arrived, far from it. It was instead populated by a diverse group of Indigenous peoples with their own cultures, traditions and languages from the Pacific Ocean in the west, to the shores of the Arctic Ocean in the north, the Great Lakes in the south, and to the Atlantic Ocean in the east. Pre-contact population estimates vary widely, but modern estimates place the population of the Pacific Northwest alone at as much as 500,000. One, therefore, wonders what the population of the entire territory that was to become Canada might have been. Sadly, European traders and settlers brought diseases, such as smallpox, to which the native population had little or no resistance. Whole communities were virtually wiped out within a short period of time. By 1867, the Canadian Indigenous population had fallen to about 125,000 souls, out of a total Canadian population of about 3.7 million, and was to continue to fall for decades after.

Nobody could live in the Ottawa region until the glaciers of the Wisconsin glacial episode had retreated sufficiently to expose the territory. This occurred roughly 11,000 years ago. Recent archaeological work has found traces of humans dating back as much as 8,000 years. Excavations at several locations along the Ottawa River have uncovered many artifacts fashioned by the Laurentian people of the Archaic period. These included the discovery of spear throwers on Allumette Island in Quebec close to Pembroke, Ontario. These implements enabled hunters to propel spears with greater force than relying on muscle power alone. Also found were tools made of stone and bone, knives crafted from slate and copper, scrapers, harpoons, fish hooks, awls and finely-made needles, the latter requiring a high degree of sophistication to manufacture. On Morrison Island, also close to Pembroke, hundreds of grinding stones were found along with axes, drills, and adzes. These early residents were highly skilled and had a strong artistic sensibility. Many bone articles had been delicately engraved.

The archaeological record also shows a continuous human presence right in the National Capital Region since those early days, reflective of its strategic position at the confluence of three major river systems—the Ottawa which flows into the St. Lawrence and from thence to the Atlantic; the Gatineau which extends northward for almost 400 kilometres; and the Rideau which, via a series of portages, provides access southward to the Great Lakes. These waterways were major transportation and trade routes for indigenous peoples, and continued as such well after the arrival of European settlers at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Indeed, the Rideau Canal built in the late 1820s traced the well-travelled indigenous route from Lake Ontario to the Ottawa River.

Indicative of the importance of the region as a trading centre, archaeological digs in the National Capital Region have uncovered an extraordinary range of material brought many hundreds if not thousands of kilometres. These include quartzite from central Quebec, different types of chert (a type of rock) used for making tools from the Hudson Bay, Illinois, and Ohio, ceramics from south of the Georgian Bay of Lake Huron, and copper from the western edge of Lake Superior. Today’s Leamy Lake Park appears to have been a key stopping point with evidence indicating continuous seasonal occupation of the delta at the mouth of the Gatineau River for over 4,500 years. There, indigenous people from all over stopped to meet, trade, and enjoy the rich bounty of natural resources to be found there.

Ottawa First Nation family, J.G. de Sauveur, Engraving, 1801, Library and Archives Canada, 2937181.Other excavations, pioneered by Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, a prominent Bytown physician, identified in 1843 an “Indian burial ground” on the northern shore of the Ottawa River. He uncovered the remains of twenty individuals in communal and individual graves. Also found at this site were ashes from cremations. Recent investigations during the twenty-first century have confirmed the location of the site as Hull Landing, immediately opposite Parliament Hill, now the location of the Canadian Museum of History.

Ottawa First Nation family, J.G. de Sauveur, Engraving, 1801, Library and Archives Canada, 2937181.Other excavations, pioneered by Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, a prominent Bytown physician, identified in 1843 an “Indian burial ground” on the northern shore of the Ottawa River. He uncovered the remains of twenty individuals in communal and individual graves. Also found at this site were ashes from cremations. Recent investigations during the twenty-first century have confirmed the location of the site as Hull Landing, immediately opposite Parliament Hill, now the location of the Canadian Museum of History.

We also know that the Chaudière Falls was a site of considerable spiritual significance to the Indigenous peoples of the region. In 1613, Samuel de Champlain described in his journal the “usual” ceremony that was celebrated at that site. He wrote that after the people had assembled, and a speech given by one of the chiefs, an offering of tobacco on a wooden plate was thrown into the roiling waters of the cauldron to seek the intercession of the gods to protect them from their enemies.

It was Samuel de Champlain who popularized the name for these indigenous peoples—the “Algoumequins” a.k.a. the Algonquins. But the people knew themselves as the Anishinabek, sometimes translated as true men, or good humans.

Following first contact with Europeans at the beginning of the seventeenth century, many eastern First Nations became embroiled in the seemingly endless conflicts between European powers for political and economic ascendancy in North America. The semi-nomadic Algonquins, who were superb hunters and trappers, became key partners with the French in the European fur trade. They supplied pelts from their own extensive territories in the Ottawa and St. Lawrence Valleys, or acted as middlemen for the Cree to the north. In exchange, the Algonquins received firearms that they used to defend themselves from their traditional rivals, the Iroquois First Nations, who were important allies of Dutch settlers to the south, and subsequently the English.

These European struggles culminated in the long conflict between England and France in the mid-eighteenth century, called the Seven Years’ War, which ultimately led to an English victory and France’s loss of its North American colonies with the exception of the important fishing centres on the islands of St. Pierre and Miquelon located in the mouth of the St. Lawrence close to Newfoundland.

When Montreal capitulated in 1760 to English forces, the English agreed to a French condition of surrender that their indigenous allies could remain in their traditional territories and would not be molested. Three years later, in June 1763, France ceded its North American territories to the English under the Treaty of Paris.

On 7 October 1763, King George III issued a Royal Proclamation outlining how his new territories in North America would be administered and how relations with the Indigenous communities would be undertaken. The Proclamation stated: “And whereas it is just and reasonable, and essential to our interest and the Security of the Colonies, that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians, with whom We are connected, and who live under our Protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories as, not having ceded to, or purchased by Us, are reserved to them, or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds.”

Another provision of the Proclamation forbade private purchases of land from Indigenous peoples, with this right reserved to the Crown. This provision set the basis for the negotiation of future treaties between the Crown and Canada’s indigenous peoples.

Notwithstanding this 1763 Royal Proclamation, Europeans quickly settled on indigenous territories. Following the American War of Independence, which ended in 1783, the Crown gave grants of land to Loyalist refugees coming north to Canadian territory according to their rank and service. These grants were given without the consent of the First Nations.

Here in the greater Ottawa area, Loyalists received grants of land on the Rideau River, including at such places as today’s Merrickville, Burritt’s Rapids, and Smiths Falls. Grants of land along the Ottawa River from Carillon westward to Fassett on the north shore in Quebec and at Hawkesbury in Ontario were also handed out.

In addition, European settlers began settling on indigenous territory in the National Capital Region in 1800 with the arrival of Philemon Wright in what is now the Hull sector of Gatineau. Initially hoping to farm, settlers almost immediately began to exploit the seemingly inexhaustible supply of pine for sale in the United Kingdom and later the United States. Settlement accelerated with the building of the Rideau Canal and the naming of Ottawa as the capital of Canada in 1857.

The clearance of vast tracks of land for farms, lumbering and urban development irrevocably altered the landscape of the Ottawa Valley. By the 1920s, less than four percent of the original, old growth forest was left. For the Algonquins, who had lived for untold centuries in harmony with nature, their way of life was also irrevocably changed. As no treaty had been made with the Crown, the Algonquin First Nations had been marginalized on their own territory. Canada’s capital continues to sit on unceded Algonquin territory in contravention of the 1763 Royal Proclamation.

Territorial claims of the Ontario Algonquins, Province of Ontario.

Territorial claims of the Ontario Algonquins, Province of Ontario.

Today, there are ten recognized Algonquin First Nations with a total population of about 11,000. Nine Algonquin communities are in Quebec—Kitigan Zibi, Barriere Lake, Kitcisakik, Lac Simon, Abitibiwinni, Long Point, Timiskaming, Kebaowek, and Wolf Lake. The tenth, Pikwakanagan, is located in Ontario. There are three additional Ontario First Nations that are related by kinship—the Temagami, the Wahgoshig and the Matchewan.

In October 2016, the Algonquins of Ontario reached an agreement-in principle-with the federal government and the government of Ontario to settle all land claims covering some 36,000 square kilometres of land in the watersheds of the Ottawa and Mattawa with a population of 1.2 million. Algonquin territorial claims in Quebec were not covered by the agreement. The agreement-in-principle is viewed as a major milestone towards reconciliation and renewed relations. If ratified, the agreement would lead to the transfer of 117,500 acres of provincial Crown land to Algonquin ownership, the provision of $300 million by the federal and provincial governments, and the definition of Algonquin rights related to lands and natural resources in Ontario. No land will be expropriated from private owners. The agreement would be Ontario’s first, modern-day, constitutionally protected treaty. As of time of writing (2021), a final agreement had not yet been reached.

Sources:

Algonquins of Ontario, 2021. Our Proud History.

Belshaw, John Douglas, 2018. “Natives by Numbers,” Canadian History: Post Confederation, BC Open Textbook Project.

Boswell, Randy & Pilon, Jean-Luc, 2015. The Archaeological Legacy of Dr. Edward Van Cortlandt, Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 39: 294-326.

Di Gangi, Peter, 2018. Algonquin Territory, Canada’s History, 30 April.

Hall, Anthony, J. 2019. Royal Proclamation of 1763, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 7 February 2006.

Hele, Carl. 2020. Anishinaabe, The Canadian Encyclopedia, 16 July.

Ontario, Government of, 2021. The Algonquin Land Claim.

Neville, George A. 2018. Loyalist Land Grants Along the Grand (Ottawa) River 1788, Bytown Pamphlet, No. 103, Historical Society of Ottawa.

Pelletier, Gérard, 1997. “The First Inhabitants of the Outaouais; 6,000 years of History,” History of the Outaouais, ed. Chad Gaffield, Laval University.

Pilon, Jean-Luc & Boswell, Randy, 2015. “Below the Falls; An Ancient Cultural Landscape in the Centre of (Canada’s National Capital Region) Gatineau,” Canadian Journal of Archaeology, 39 (257-293).

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Ottawa the Beautiful: The Gréber Report

18 November 1949

Ottawa is undoubtedly a beautiful city. Blessed by geography, the city borders the mighty Ottawa River, and is bisected by the Rideau River and the Rideau Canal, one of only eight UNESCO world heritage sites in Canada. Reputedly, Ottawa has 8 hectares (20 acres) of parklands for every 1,000 residents, compared to only 3.2 hectares (8 acres) of green space for every 1,000 Toronto residents, and a miniscule 1.2 hectares (3 acres) for every 1,000 Montréalais. And that’s not counting Gatineau Park that encompasses 361 square kilometres (139 square miles) of rolling hills and pristine lakes, and extends close to the centre of Gatineau, Quebec, just a few minutes’ drive from Parliament Hill.

Befitting a capital city, Ottawa can also boast magnificent governmental, cultural, and historic buildings and monuments. The National Capital Commission’s “Confederation Boulevard,” which is bordered with broad, tree-line sidewalks, runs along Sussex Drive and down Wellington Street before looping across the Ottawa River and along rue Laurier in Gatineau before returning to Ottawa. On this ceremonial route, one can find the stately homes of the Governor General and the Prime Minister, Canada’s National Gallery, the War Memorial, the storied Château Laurier Hotel, and the Canadian Museum of History. Of course, the crown jewels of the route are Canada’s iconic Gothic Revival Parliament buildings on Wellington Street, perched on a bluff overlooking the Ottawa River.

While a beautiful and extremely livable city, Ottawa is not without blemish. Sparks Street, once the commercial heart of the city, hardly beats these days, while parts of Bank and Rideau Streets are tired and shop-worn. And let’s not talk about LeBreton Flats. But Ottawa is redeemed by its parks and gardens, flourishing neighbourhood communities, thriving markets, and leafy parkways that border its waterways.

Not that long ago, however, Ottawa was a grim, dirty, industrial town; crumbling buildings and blighted neighbourhoods were but a short distance of the Parliament buildings. During World War II, most of the downtown green spaces was filled with “temporary” wooden office buildings hastily constructed to house the Capital’s burgeoning civil service. The city’s natural beauty was also threatened with unplanned urban sprawl, while its waterways were fouled by the detritus of the area’s extensive wood-products industry and the untreated sewage of its mushrooming population.

Efforts to improve the city began shortly after Confederation with the creation of Major’s Hill Park in 1874. In 1899, three years after Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier voiced his desire for Ottawa to become the “Washington of the North,” the first city improvement committee called the Ottawa Improvement Commission (later the Federal District Commission) initiated a number of landscaping projects, including the Rideau Canal Driveway. A series of urban planning studies were subsequently commissioned, including the Todd Report in 1903, the Holt Commission in 1915, and the Cauchon Report in 1922. Their recommendations included an expansion of Ottawa parklands, the rationalization of the city’s tangle of railway lines, and the enforcement of building regulations. Broadly speaking, however, little was achieved owing to changing government priorities, war, and the Great Depression. One idea that initially found traction but ultimately also failed was the suggestion of forming a National Capital District, akin to the District of Columbia in the United States, that would encompass the cities of Ottawa in Ontario and Hull in Quebec, along with their hinterlands. Political opposition, notably from Quebec, and concerns about the linguistic future of the area’s francophone residents scuppered the idea.

Another effort at rejuvenating Ottawa’s downtown core close to the Parliament buildings began in 1937 under the guidance of Jacques Gréber, a noted French urban planner whom Prime Minister Mackenzie King had met at the Paris Exhibition (Exposition Internationale des Arts et Techniques dans la Vie Moderne) held that same year. Gréber had been the Chief Architect of the Exhibition. When the two men hit it off, King asked Gréber to come to Ottawa to help prepare long-term plans for the development of government buildings along Wellington Street and in adjacent areas. However, war broke out before much could be achieved beyond the construction of the National War Memorial at the intersection of Wellington and Elgin Streets.

Immediately following the end of World War II, Mackenzie King invited Gréber back to Ottawa to head a far larger urban planning project—devising a long-term development plan for the entire 2,300 square kilometre (900 square miles) National Capital Region. Gréber was a controversial choice. The Royal Architectural Institute of Canada objected, writing a letter to Mackenzie King saying that the National Capital development project should have been entrusted to a group of Canadian specialists rather than to a foreigner. Officially, responsibility for the project rested with the 17-member National Capital Planning Committee composed of representatives of the cities of Ottawa and Hull and area counties, the chairman of the Federal District Commission (FDC), the Federal Minister of Public Works, Canadian professional institutes, including the Royal Architectural Institute of Canada, and others. While Gréber was clearly the lead consultant, he was supported by the FDC and a staff of Canadian architects and engineers.

Jacques Gréber shows off the model of his plan for the National Capital to Members of Parliament, 30 April, 1949.The final 300-page report, along with the accompanying volume of maps, watercolours, and scale model of the city, was released on 18 November 1949 after more than four years of work. Mackenzie King, who had retired as prime minister the previous year, wrote the foreword to the report. In many ways, Gréber’s plan for the National Capital was King’s legacy to the country. The plan was also dedicated as a memorial to Canadian service people who died in World War II.

Jacques Gréber shows off the model of his plan for the National Capital to Members of Parliament, 30 April, 1949.The final 300-page report, along with the accompanying volume of maps, watercolours, and scale model of the city, was released on 18 November 1949 after more than four years of work. Mackenzie King, who had retired as prime minister the previous year, wrote the foreword to the report. In many ways, Gréber’s plan for the National Capital was King’s legacy to the country. The plan was also dedicated as a memorial to Canadian service people who died in World War II.

Before discussing its recommendations and their justification, the Report provided an in-depth survey of the National Capital Region, covering its physical characteristics, history, demographics, land use, housing, public buildings, transportation systems, with a special section on the railways, and recreational/touristic facilities. Sometimes the Report is more poetry than prose, referring, for example, to the “broad bosomed” Ottawa River and the “boisterous leaping Chaudière.” At one point it strays into conjecture, uncritically accepting the unsubstantiated claim that the 1916 fire that demolished the Centre Block on Parliament Hill was “set by a German hand.” Despite such quibbles, the Report is exhaustive, and makes a compelling case for its sweeping urban renewal plans for downtown Ottawa-Hull, and the preservation of rural greenspaces.

The key recommendation was the relocation of the railways and associated rail yards and warehouses out of the downtown core. Gréber argued that the tracks had been laid to serve the interest of their operators and the lumber barons rather than those of the broader community. Originally on the outskirts of the city, the railways had been constructed without regard for future urban expansion. In addition to beautifying the city, their removal would return the city to its citizens by eliminating rail barriers that divided neighbourhoods, improve safety, and speed traffic circulation. Replacing the railways would be a network of highways, urban arteries, and tree-line parkways. Gréber recommended the construction of two new bridges across the Ottawa River on the outskirts of the city that would link the Ontario and Quebec highway systems, one in the west over Nepean Bay at Lemieux Island, and another in the east over Upper Duck Island. Gréber also sought the elimination of Ottawa’s trolleys as their overhead wires and related infrastructure in the downtown core detracted from the beauty and monumental nature of the area.

Other important recommendations included urban renewal for blighted neighbourhoods close to Parliament Hill, such as LeBreton Flats, the elimination of the war-time “temporary” buildings that littered the city, the imposition of strict building regulations to preserve the view of Parliament Hill, and the decentralization of government operations. To address urban sprawl, Gréber recommended that the Government acquire land to build a greenbelt around the city. He also favoured the expansion of Gatineau Park and the preservation of neighbouring forests and rural areas for recreational and touristic purposes. In downtown Ottawa, he recommended the construction of a number of large monumental buildings, including an Auditorium and Convention Centre on Lyon Street between Sparks and Albert Streets, the establishment of a National Theatre on Elgin Street, a National Gallery on Cartier Square, and a National Library on Sussex Street, north of Boteler Street. Noting that, a “capital without a dignified City Hall is a paradox,” Gréber proposed the construction of a new Ottawa City Hall to replace the one destroyed by fire in 1931 but never rebuilt. His proposed building fronted on Nicholas Street with a new bridge across the Rideau Canal at that point. He also recommended relocating Carleton College (the forerunner of Carleton University) to the fields of the Experimental Farm along Fisher Avenue. Finally, in keeping with the idea that the redesigned National Capital Region would be a memorial to Canada’s war heroes, Gréber planned a giant memorial terrace at the southernmost point of the Gatineau Hills with “an imposing panoramic view” of Ottawa.

As one might expect with any such sweeping plan, there was opposition; many of Gréber’s recommendations were rejected or ignored. But the French urban planner got his way on two key recommendations—the relocation of the railways out of downtown Ottawa, and the establishment of a greenbelt. Through land swaps between the FDC and the railways companies, downtown Union Station, which was across the street from the Château Laurier Hotel, was replaced with a new passenger station built south of the city on Tremblay Road. The unsightly, 600 foot long, train shed at Union Station was demolished, and the tracks that ran alongside the Rideau Canal were removed, making way for Colonel By Drive. Similarly, the Ottawa West freight station and tracks at LeBreton Flats were expropriated. Ottawa’s rattling trams with their unsightly overhead wires were also retired in favour of more economical buses. Earning the gratitude of future residents, the Federal Government was also able to push through Gréber’s greenbelt proposal south of the Capital, despite opposition from suburban townships—Nepean politicians called the greenbelt the “weed belt.”

On other issues, Gréber was less successful. His idea of a huge war memorial in Gatineau was dropped owing to opposition from veterans who wished to commemorate World War II dead at the National War Memorial in downtown Ottawa. Most of the monumental buildings he planned for the downtown core were never built, or were located elsewhere, though his call for the demolition of the “temporary” war-time office buildings was heeded, albeit over a very long time, with the last one—the Justice Annex to the east of the Supreme Court building—only succumbing to the wrecking ball in 2012. His attempt to preserve the view of Parliament Hill from the south through height restrictions on commercial buildings also failed as high-rise office buildings, constructed to house federal civil servants, blocked the view. Similarly, his attempt to rejuvenate the LeBreton Flats took more than a generation to get underway owing in part to changing government priorities and inertia. Fifty years after the blighted neighbourhood was demolished, it remains a work in progress.

With hindsight, Gréber’s preference for the automobile over trains and trams, also had its downside, in part because he grossly under-estimated the expected future population of the National Capital Region. He had anticipated a population on the order of 500,000-600,000 by 2020, compared to 1.4 million today. Like the railways that preceded them, highways and major urban arteries came to divide neighbourhoods. A case in point is the Queensway which replaced the east-west CN rail line; Gréber had envisaged a tree-lined boulevard. Many mourn the loss of a downtown train station, and the passing of the city’s tram lines. The failure to build two new bridges across the Ottawa River at the city’s periphery linking the Ontario and Quebec highway systems has meant that interprovincial traffic continues to be routed across downtown bridges, aggravating traffic woes. Finally, the development of the greenbelt did little to stop urban sprawl as Gréber had hoped. Instead of the greenbelt promoting the development of self-contained satellite communities as he had envisaged, the automobile permitted them to become bedroom communities for Ottawa, and in the process further contributed to traffic congestion.

In sum, the Gréber Plan was marred by faulty assumptions and inadequate follow-through. But, despite all, Ottawa was transformed from a grimy, industrial city to a capital Canadians can be proud of. For that, we must give a big hand to the vision of Jacques Gréber.

Sources:

Butler, Don, 2012. “Putting things back on track for Ottawa’s train station,” 27 May, The Ottawa Citizen, http://www.ottawacitizen.com/news/Putting+things+back+track+Ottawa+train+station/6690940/story.html.

City of Ottawa, 2010-15. Relocating the Rail Lines, http://ottawa.ca/en/residents/arts-culture-and-community/museums-and-heritage/witness-change-visions-andrews-newton-6.

Gordon, David. 2000. Weaving a Modern Plan for Canada’s Capital: Jacques Gréber and the 1950 Plan for the National Capital Region, https://qshare.queensu.ca/Users01/gordond/planningcanadascapital/greber1950/Greber_review.htm.

Théoret, Huger, 2013. “Le plan Gréber dévoilé aux Communes,” Le Droit, 8 mars.

NCC Watch, 2003(?). NCC Blunders: Ottawa’s Union Station, http://nccwatch.org/blunders/unionstation.htm.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1945. “Canadian Architectural Institute Protest Hiring of Jacques Greber,” 2 October.

———————-, 1945. “Jacques Greber Arrives to Plan National Capital,” 2 October.

National Capital Planning Committee, 1950. “Plan for the National Capital,” (The Gréber Report), https://qshare.queensu.ca/Users01/gordond/planningcanadascapital/greber1950/index.htm.

Macleod, Ian, 2014. “The lost train of nowhere,” The Ottawa Citizen, 18 December, http://ottawacitizen.com/news/local-news/from-the-archives-the-lost-train-of-nowhere.

Images:

Intersection of Wellington Street and Lyon Street, looking south, 1936, the Gréber Report, Illustration #153.

Jacques Gréber shows off the model of his plan for the National Capital to Members of Parliament, 30 April, 1949,National Capital Commission, 172-5, http://www.lapresse.ca/le-droit/dossiers/100-evenements-historiques/201303/08/01-4629049-16-le-plan-greber-devoile-aux-communes.php.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.