Since September 2020, the Historical Society of Ottawa has presented a virtual speakers series using Zoom. A full recording of those presentations is available on the HSO YouTube channel and shown here as well.

The Historical Society of Ottawa does not necessarily subscribe to views expressed in these videos, nor take any responsibility for their content.

Thomas Mackay & The Making of Ottawa

Alastair Sweeny, author of "Thomas Mackay, The Laird of Rideau Hall and the Founding of Ottawa" recounts the beginning of Bytown.

A Local Canvas: Paintings from the Bytown Museum Collection

Bytown Museum's Collections and Exhibitions Manager, Grant Vogl, gives a snapshot of the vast collection of art works held within the museum's vault.

June & Company’s Great Oriental Circus

12 August 1851

Life was hard in Bytown during the mid-nineteenth century. The small community, which was to become Ottawa, had perhaps 7,000 souls. People laboured long hours, six days of the week, for low pay. For tired workers after-work entertainment options were limited. Many simply repaired to their neighbourhood watering hole. For the well-to-do, Hough’s Dramatic Company, a troupe of five ladies and ten gentlemen, put on dramatic productions—tragedies, dramas and farces—at the Union Hall. A seat at their performances cost 1s. 3d., the equivalent of 25 cents. Those looking to improve themselves could join the Mechanics Institute and Athenaeum or l’Institut canadien français d’Ottawa. Both organizations, which were established in the early 1850s, put on edifying lectures and organized reading rooms and small libraries for their subscribers. For the sportsman, pigeon shooting on Major’s Hill was another popular activity during the annual spring and fall migrations—at least it was until most of the trees were cut down sometime before 1860 destroying the birds’ roosting sites.

Given this limited range of entertainment possibilities, imagine the excitement when a circus came to town. For most people, it was their only exposure to the outside world, enabling them to see exotic animals, mysterious peoples, and astonishing acts that they could otherwise only dream about.

Advertisement for the June & Company’s Great Oriental Circus, The Ottawa Citizen, 26 July 1851.The June & Company’s Great Oriental Circus operated by James M. June with his partner Seth Howes came to Canada in 1851 with stops in Montreal and Toronto before coming to Bytown for a three-day visit from the 12 to 14 August, 1851. This was at least the second visit by Seth Howes. In the summer of 1840 he had brought the Equestrian Exhibition of the National Circus of New York to little Bytown which what was then little more than a remote lumbering village.

Advertisement for the June & Company’s Great Oriental Circus, The Ottawa Citizen, 26 July 1851.The June & Company’s Great Oriental Circus operated by James M. June with his partner Seth Howes came to Canada in 1851 with stops in Montreal and Toronto before coming to Bytown for a three-day visit from the 12 to 14 August, 1851. This was at least the second visit by Seth Howes. In the summer of 1840 he had brought the Equestrian Exhibition of the National Circus of New York to little Bytown which what was then little more than a remote lumbering village.

As the railway had not yet linked Bytown to the outside world, the circus must have travelled to the town by road—an onerous journey given the quality of inter-city highways of that era. The entrance fee was 1s. 3d. There was no price reduction for children; early circuses did not cater to youngsters.

The June & Company circus entered Bytown with the band car in front drawn by its eight Syrian camels “imported at vast expense expressly for this Establishment.” The circus’s advertisement also promised “a greater variety of startling and attractive entertainments than ever before been given by any single Troupe, for the effectual production of which an ‘Unparalleled Array of Talent’ has been secured.” As you can see, circus bombast started early. Most of the circus performances were equestrian in nature. Featured artists included Laverter Lee, the “great English EQUILIBRIST and DOUBLE RIDER, and his Talented Children.” The very large Lee family, which had immigrated to the United States in the 1840s, was a notable show family that provided a number of fine equestrians. The family is also reputed to have invented the “perch act,” where one performer conducts a series of acrobatic tricks on top of a pole that is being balanced by another performer. William H. Cole and his wife Mary Anne also performed. William Cole was a famed contortionist and clown. His wife was a renowned equestrienne who was billed to have come from Astley’s Amphitheatre in England. Astley’s was a famed London circus performance venue during the nineteenth century. Mary Anne Cole was the star of a show called “EXERCISES OF THE MANEGE.” Other featured equestrians were Mrs Caroline Sherwood, Mr. Lipman, “the distinguished dramatic rider” and Mr Sherwood, “the rapid rider.” The acrobats Messrs MacFarland and Sweet also performed. MacFarland was renowned for having executed eighty-seven successive somersaults. To round out the show was the clown John Gossin. Gossin, who was coming to the end of his career when he performed with the June circus, was a witty raconteur as well as a rider and tumbler. In the course of each performance, which started at 2.30 pm and 7.30 pm each day, the camels were introduced in “a new and magnificent Oriental Pageant” called the Caravan of the Desert, “representing the means of travelling in in the East and an Encampment of Wandering Arabs.”

News of the circus’s arrival in Bytown prompted controversy as well as excitement. A week prior to its appearance, a small critical article appeared in The Ottawa Citizen. It read “He of the Gazette,” in noticing the June & Company’s advertisement in the newspaper, invited readers to “a lecture on the immorality of such exhibitions.” While unnamed, “he of the Gazette” was William F. Powell, a prominent Bytown citizen who had been the editor of the Bytown Gazette. He was to become the Conservative Member of Parliament for Carleton Country in 1854. (Powell Avenue in the Glebe neighbourhood is named in his honour.)

Robert Bell, the reformist and liberal-minded editor of The Ottawa Citizen, mocked Powell. He opined that June & Co. was a “most respectable company,” and that he was “at a loss to appreciate justly the various performances, and the decent and becoming manner with which it was carried on.” He added “Really the Editor of the Gazette is impayable [priceless], when forgetting who he is, he robes himself in the garb of the casuist, and decides for the spiritual benefit of his townsmen, what sort of amusement they are to have, and what are those which might prove detrimental to their morals.” Given the warm reception given to the Circus by Bytown’s residents, Bell said Powell was “preaching in the desert.” Bell described the performance of Mrs Cole as “lady-like,” and that she had managed her spirited horse in an elegant manner. He also thought Mrs Sherwood was a good equestrian performer. As well, he praised highly the performance of the circus men especially that of John Gossin who Bell described as “a spirited and merry Clown of the troupe who kept the audience in a constant fit of laughter.” In one of the Circus’s performances, Gossin’s jokes about Powell, elicited “a roar of laughter.” Bell hoped that that would teach Powell that his position in the community “is not such as to warrant his giving advices as to what is morally becoming to the ladies of Bytown.”

After June & Company, other circuses stopped regularly in Bytown and later Ottawa through the remainder of the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth. Once the city was accessible by rail, productions also became bigger and more elaborate owing to both supply and demand reasons. Rail service lifted the constraints on what travelling circuses could transport from town to town at reasonable cost. This allowed them to respond to competitive pressures for new and more bizarre acts from increasingly jaded audiences who had become bored with equestrians, tumblers and clowns, the mainstay of early circuses. Perhaps the greatest circuses of the late nineteenth century that came to Ottawa was the famous Barnum & Bailey Circus, billed as “The Greatest Show on Earth.” So fantastic was the Barnum & Bailey Circus, it warrants its own story.

Sources:

Brown, Col. T. Allston, 1994. Amphitheatres & Circuses, Emeritus Enterprise, San Bernardino, California.

Bytown Gazette (The), 1840. “National Circus–From The City Of New York,” 27 August.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1851. “June and Co.’s Splendid Oriental Circus,” 9 August.

————————-, 1851. “Theatre,” 16 August.

————————-, 1851. “The Circus,” 16 August.

Circus Historical Society, 2002, http://www.circushistory.org/index.htm.

Slout, William L, 2002. Chilly Billy, The Evolution of a Circus Millionaire, Emeritus Enterprise: San Bernardino, California.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Sappers' Bridge

23 July 1912

It ended with a crash that sounded like a great gun going off, the noise reverberating off the buildings of downtown Ottawa. After faithfully serving the Capital for more than eighty years, Sappers’ Bridge finally succumbed to the wreckers in the wee hours of the morning of Tuesday, 23 July 1912. However, the old girl didn’t go gently into that good night. It took seven hours for the structure to finally collapse in pieces into the Rideau Canal below. After trying dynamite with little success, the demolition crew rigged a derrick and for hours repeatedly dropped a 2 ½ ton block onto the platform of the bridge before the arch spanning the Canal gave way. Mr. O’Toole the man in charge of the demolition, said that the bridge was “one of the best pieces of masonry that he [had] ever taken apart.”

View of the Rideau Canal and Sappers’ Bridge – Painting by Thomas Burrowes, c. 1845, Archives of Ontario, Wikipedia.The bridge, the first and for many decades the only bridge across the Rideau Canal, dated back to the dawn of Bytown. In the summer of 1827, Thomas Burrowes, a member of Lieutenant Colonel John By’s staff, gave his boss a sketch of a proposed wooden bridge to span the Rideau Canal, which was then under construction, from the end of Rideau Street in Lower Bytown on the Canal’s eastern side to the opposing high ground on the western side. Colonel By accepted the proposal but opted in favour of building the bridge out of stone rather than wood. Work got underway almost immediately, with the foundation of the eastern pier begun by Mr. Charles Barrett, a civilian stone mason, though the vast majority of the workers were Royal Sappers and Miners. On 23 August 1827, Colonel By laid the bridge’s cornerstone with the name Sappers’ Bridge cut into it. The arch over the Canal was completed in only two months. On the keystone on the northern face of the bridge, Private Thomas Smith carved the Arms of the Board of Ordnance who owned the Canal and surrounding land. The original bridge was only eighteen feet wide and had no sidewalks.

View of the Rideau Canal and Sappers’ Bridge – Painting by Thomas Burrowes, c. 1845, Archives of Ontario, Wikipedia.The bridge, the first and for many decades the only bridge across the Rideau Canal, dated back to the dawn of Bytown. In the summer of 1827, Thomas Burrowes, a member of Lieutenant Colonel John By’s staff, gave his boss a sketch of a proposed wooden bridge to span the Rideau Canal, which was then under construction, from the end of Rideau Street in Lower Bytown on the Canal’s eastern side to the opposing high ground on the western side. Colonel By accepted the proposal but opted in favour of building the bridge out of stone rather than wood. Work got underway almost immediately, with the foundation of the eastern pier begun by Mr. Charles Barrett, a civilian stone mason, though the vast majority of the workers were Royal Sappers and Miners. On 23 August 1827, Colonel By laid the bridge’s cornerstone with the name Sappers’ Bridge cut into it. The arch over the Canal was completed in only two months. On the keystone on the northern face of the bridge, Private Thomas Smith carved the Arms of the Board of Ordnance who owned the Canal and surrounding land. The original bridge was only eighteen feet wide and had no sidewalks.

Reportedly, one of the first civilians to cross Sappers’ Bridge was little Eliza Litle (later Milligan), the six-year old daughter of John Litle, a blacksmith who had set up a tent and workshop where the Château Laurier Hotel stands today. Apparently, Eliza was playing close to the Canal bank on the western side when she was frightened by some passing First Nations’ women. She ran screaming towards Sappers’ Bridge which was then under construction. A big sapper picked Eliza up and carried her over a temporary wooden walkway and dropped her off at her father’s smithy.

Back in those early days, there were two Bytowns. Most people lived in Lower Bytown. It had a population of about 1,500 souls, mostly French and Irish Catholics. The much smaller Upper Bytown, which was centred around Wellington Street roughly where the Supreme Court is situated today, had a population of no more than 500. This was where the community’s elite lived, mainly English and Scottish Protestants. The two distinct worlds, one rowdy and working class, the other stuffy and upper class, were linked by Sappers’ Bridge. While the bridge joined up Rideau Street on its eastern side, there was only a small footpath on its western side. The path wound its way around the base of Barrack Hill (later called Parliament Hill), which was then heavily wooded, past a cemetery on its south side that extended from roughly today’s Elgin Street to Metcalfe Street, until it reached the Wellington and Bank Streets intersection where Upper Bytown started. It wasn’t until 1849 that Sparks Street, which had previously run only from Concession Street (Bronson Avenue) to Bank Street, was linked directly to Sappers’ Bridge. During the 1840s, that stretch of path to Sappers’ Bridge was a lonely and desolate area. It was also dangerous, especially at night. It was the favourite haunt of the lawless who often attacked unwary travellers. Many a score was settled by somebody being turfed over the side of the bridge into the Canal. People travelled across Sappers’ Bridge in groups: there was safety in numbers.

Bytown, which became Ottawa in 1855, quickly outgrew the original narrow Sappers’ Bridge. In 1860, immediately prior the visit of the Prince of Wales who laid the cornerstone of the Centre Block on Parliament Hill, six-foot wide wooden pedestrian sidewalks supported by scaffolding were added to each side of the existing stone bridge. This permitted the entire 18-foot width of the bridge to be used for vehicular traffic.

But only ten years later, the bridge was again having difficulty in coping with traffic across the Rideau Canal. There was discussion on demolishing Sappers’ Bridge and replacing it with something much wider. The Ottawa Citizen opined that such talk verged on the sacrilegious as Sappers’ Bridge was “an old landmark in the history of Bytown.” The newspaper also thought that it was far too expensive to demolish especially as the bridge had “at least another century of wear in it.” It supported an alternative proposal to build a second bridge over the Canal.

In late 1871, work began on the construction of that second bridge across the Canal linking Wellington Street to Rideau Street, immediately to the north of Sappers’ Bridge. It was completed at a cost of $55,000 in 1874. It was called the Dufferin Bridge after Lord Dufferin, Canada’s Governor General at that time. Another $22,000 was spent on widening the old Sappers’ Bridge on which were laid the tracks of the horse-drawn Ottawa Street Passenger Railway.

Despite the upgrade, Ottawa residents were still not happy with the old bridge. Sappers’ Bridge was a quagmire after a rainstorm. On wag stated that “It is estimated that the present condition of the bridge has produced more new adjectives that all the bad whiskey in Lower Town.” One Mr. Whicher of the Marine and Fisheries Department was moved to write a 24-verse parody of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s poem The Bridge about Sappers’ Bridge. In it, he referred to “many thousands of mud-encumbered men, each bearing his splatter of nuisance.” He hoped that a gallant colonel “with a mine of powder, a pick and a sure fusee (sic)” would blow it up. His poem was well received when he recited it at Gowan’s Hall in Ottawa.

But it took another thirty-five years before the government contemplated doing just that. As part of Sir Wilfrid Laurier’s plan to beautify the city and make Ottawa “the Washington of the North,” the Grand Trunk Railway began in 1909 the construction of Château Laurier Hotel on the edge of Major’s Hill Park, and a new train station across the street. Getting wind of government plans to build a piazza in the triangular area above the canal between the Dufferin Bridge and Sappers’ Bridge in front of the new hotel, Mayor Hopewell suggested that Sappers’ Bridge might be widened as part of these plans in order to permit the planting of a boulevard of flowers and rockeries to hid the railway yards from pedestrians walking over the bridge. He also added that public lavatories might be installed beneath the piazza.

Demolition of Sappers’ Bridge, 1912. The arch of Sapper’s bridge is gone leaving only the broken abutments and rubble in the Canal. The newly built Château Laurier hotel in in the background on the right. Dufferin Bridge is in the centre of the photograph. Bytown Museum, P799, Ottawahh.In the event, the federal government decided to demolish Sappers’ Bridge. Both the Dufferin and Sappers’ Bridges were replaced by one large bridge—Plaza bridge. This new bridge was completed in December 1912. The piazza over the Canal was also built. It was bordered by the Château Laurier Hotel, Union Station, the Russell House Hotel and the General Post Office. A straw poll conducted by the Ottawa Citizen newspaper of its readership, favoured naming the new piazza “The Plaza.” However, the government, the owner of the site, had other ideas. It decided on calling it Connaught Place, after Lord Connaught, the third son (and seventh child) of Queen Victoria who had taken up his vice-regal duties as Canada’s Governor General in 1911.

Demolition of Sappers’ Bridge, 1912. The arch of Sapper’s bridge is gone leaving only the broken abutments and rubble in the Canal. The newly built Château Laurier hotel in in the background on the right. Dufferin Bridge is in the centre of the photograph. Bytown Museum, P799, Ottawahh.In the event, the federal government decided to demolish Sappers’ Bridge. Both the Dufferin and Sappers’ Bridges were replaced by one large bridge—Plaza bridge. This new bridge was completed in December 1912. The piazza over the Canal was also built. It was bordered by the Château Laurier Hotel, Union Station, the Russell House Hotel and the General Post Office. A straw poll conducted by the Ottawa Citizen newspaper of its readership, favoured naming the new piazza “The Plaza.” However, the government, the owner of the site, had other ideas. It decided on calling it Connaught Place, after Lord Connaught, the third son (and seventh child) of Queen Victoria who had taken up his vice-regal duties as Canada’s Governor General in 1911.

In the 1920s and 1930s, the beautification of downtown Ottawa continued. The Federal District Commission, the forerunner of the National Capital Commission, expropriated the Russell Block of buildings and the Old Post Office to provide space for a national monument to honour Canada’s war dead. The war memorial was officially opened in 1939 by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth. In the process, Connaught Place was transformed into Confederation Square.

Little now remains of the old Sappers’ Bridge. Hidden underneath the Plaza Bridge is a small pile of stones preserved from the old bridge with a plaque installed by the NCC in 2004 in honour of Canadian military engineers. The bridge’s keystone with the chiselled emblem of the Ordnance Board was also saved from destruction. For a time it was housed in the government archives building but its current location is unknown.

Sources:

Ross, A. H. D. 1927. Ottawa Past and Present, Toronto: The Musson Book Company.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1871. “editorial,” 3 May.

————————, 1972. “A Dirty Bridge,” 10 April.

————————, 1874. “Sappers’ Bridge,” 9 October.

————————, 1913. “‘Connaught Place’, Cabinet’s Choice of Name for Area Formed By Union of Sappers’ and Dufferin Bridges,” 24 March.

————————, 1925. “Muddy Sappers’ Bridge In the Seventies,” 18 July.

———————–, 1928. “Girl of Six Was the First Female To Cross Sappers’ Bridge Over Canal,” 23 June.

The Ottawa Evening Journal, 1910. “Widening of the Bridges,” 3 June.

———————————–, 1912. “Early Days In Bytown Some Reminiscences,” 27 April.

———————————–, 1912. “When Ottawa Was Chosen The Capital of Canada,” 4 May.

———————————–, 1912. “Bridge Is Blown Down,” 23 July.

———————————–, 1914. “Notable Stones In the History Of The Capital,” 16 March.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

The Corporation of Bytown

28 July 1847

Municipal elections don’t get the respect they deserve in Canada. Invariably, far fewer people vote in them than they do in their provincial or federal counterparts. And Ottawa’s municipal elections are no exception. In the 2018 election, the percentage of registered voters who actually voted was less than 43 per cent. In comparison, two-thirds of registered Canadian voters exercised their franchise in the 2015 federal election. Reasons for municipal voters’ apathy include a lack of awareness about what local candidates stand for, and a feeling that municipal governments don’t matter very much. Two hundred years ago, the sentiment was very different. The quest for independent, municipal governments responsible to local ratepayers was a potent political issue that divided communities.

When British sympathizers fled northward following the American Revolution, they brought with them the democratic processes that they had grown up with in New York, Pennsylvania, and New England. These included elected municipal officials and town hall meetings where local issues were publicly thrashed out. For British military leaders in what was to become Canada, such democratic ideas were anathema. After all, hadn’t democracy led to the loss of the southern American colonies? In their view, free elections, even at the local level, threatened peace and order. What was needed was the firm guiding hand of Crown-appointed magistrates and officials.

In 1791, Quebec was divided into two parts under the Constitutional Act—Lower Canada where the French civil code and customs prevailed and Upper Canada where British common law and practices were introduced to accommodate the many English-speaking, United Empire Loyalists. However, General Simcoe, Upper Canada’s first lieutenant governor, was loath to permit democratic notions from taking root in Canada. He was appalled when one of the first acts of the Assembly of Upper Canada was to approve town meetings for the purpose of appointing local officials. He stalled and prevaricated, favouring instead a system of municipal government guided by justices of the peace appointed by the Crown. It took decades for real democracy to be introduced. In the interim, power at both the provincial and municipal level was tightly controlled by a small group of powerful merchants, lawyers and Church of England clergymen who became known as the Family Compact.

Cracks in this authoritarian structure began to show in 1832 when Brockville won the right to have an elected Board of Police. Other towns quickly followed suit. In 1834, the town of York became the city of Toronto under its radical first mayor William Lyon Mackenzie, and held direct elections for its mayor and its aldermen. In 1835, a new Act of the Provincial Assembly transferred municipal powers from the justices of the peace to elected Boards of Commissioners. However, this democratic reform was repealed amidst the Rebellions of 1838 by resurgent conservative forces who managed to frame the debate as between order and loyalty to the Crown on one side and disorder and republican disloyalty on the other.

This set the stage for Lord Durham’s famous investigation into the causes of the Rebellions and possible solutions. In his Report made public in 1839, Durham recommended the introduction of responsible government in Canada with ministers responsible to an elected assembly rather than appointed by the Crown. He also said that “the establishment of a good system of municipal institutions throughout the Province [Upper Canada] is a matter of vital importance. In 1841, the District Council Act was passed by Parliament. It was a compromise between conservative (Tory) forces that wanted to maintain central control over local affairs in order to ward off republicanism and radical (Reform) forces that wanted total local self-government. Districts would be governed by a warden appointed by the Crown and a body of elected councillors. While some municipal officials were appointed by the councillors, certain positions, including that of treasurer, would continue to be appointed by the Crown. It wasn’t until the “Baldwin Act” of 1849 (named for Robert Baldwin) that municipalities in Upper Canada were granted wide powers of self-administration.

The broad forces that were in play in Upper Canada were also in play in little Bytown which was established in 1826 by Lieutenant-Colonel By, the architect of the Rideau Canal. Initially, it was a military town where the British Ordnance Department was the dominant player in the local administration and a major landowner. In the 1830s, Bytown became part of Nepean Township and subsequently the “capital” of the Dalhousie District with an appointed warden. In addition to Bytown, other communities represented in Dalhousie District included Nepean, Gloucester, North Gower, Osgoode, Huntley, Goulbourn, Marlborough, March, Torbolton, and Fitzroy. It was a cumbersome arrangement owing to the size of the district and poor roads.

On 28 July 1847, Bytown gained new status when the Governor General gave his assent to “An Act to define the limits of the Town of Bytown, to establish a Town Council therein, and for other purposes.” Bytown was divided into three wards, with elections held in mid-September for seven town councillors—two from each of North and South Wards and three from West Ward. North and South Wards encompassed Lower Bytown, the home of mainly working class, Roman Catholic, Irish and French settlers. West Ward contained Upper Bytown, the smaller of the two Bytowns, and the home of the upper-class, Protestant, English elite. Given these demographics, Lower Town was broadly Reform territory, while Upper Town was a Tory bastion.

With eligible voters limited to male ratepayers, there weren’t many voters—only 878 men voted in that first Bytown election. Voting was also public. A secret ballot wasn’t introduced until the Baldwin Act was passed two years later. At the time, a secret ballot was widely perceived as being cowardly and a voting method that promoted political hypocrisy. Elected were Messrs. Bedard and Friel from North Ward, Messrs. Scott and Corcoran in South Ward and Messrs. Lewis, Sparks and Blasdell in West Ward. With the four elected from the North and South Wards all reformers, they held a narrow one-vote majority on Council over the three Tory victors elected in West Ward. At the first session of Council, John Scott was elected Bytown’s first mayor by the seven elected councillors who split down political lines: four Reformers versus three Tories.

Portrait of John Scott, First Mayor of Bytown, 1848 by William Sawyer, City of Ottawa.In January 1848, John Scott was also elected to the Provincial Parliament as the member for Bytown—this was an era when politicians could hold multiple elected posts simultaneously. In the second municipal election held the following April, Scott chose not to run leading to the election of Tory John Bower Lewis as the second Mayor of Bytown. In 1849, fellow Tory, Robert Hervey, was chosen as Mayor.

Portrait of John Scott, First Mayor of Bytown, 1848 by William Sawyer, City of Ottawa.In January 1848, John Scott was also elected to the Provincial Parliament as the member for Bytown—this was an era when politicians could hold multiple elected posts simultaneously. In the second municipal election held the following April, Scott chose not to run leading to the election of Tory John Bower Lewis as the second Mayor of Bytown. In 1849, fellow Tory, Robert Hervey, was chosen as Mayor.

Hervey’s term in office was marred by two major political events—the Stony Monday riots in September 1849 in which Tories and Reformers came to blows, inflamed by Hervey’s own partisan actions and rhetoric, and the disallowance of the very Act of Parliament that had incorporated Bytown two years earlier.

The disallowance of the Act has its roots in a dispute between the Town Council and the Ordnance Department. Under its Act of Incorporation, Bytown had the right to expropriate land. Using this power, the Town Council expropriated a strip of Ordnance property along Wellington Street for the purpose of continuing the street “over the hill between the two towns to meet Rideau Street, in a direct line” at Sappers’ Bridge. At that time, Wellington Street made a bulge around the base of Barrick Hill (later known as Parliament Hill). But with the construction of Sparks Street immediately south of Wellington Street to Sappers’ Bridge following the settlement of another dispute over the ownership of the Government Reserve between Ordnance and Nicholas Sparks in Sparks’ favour, Town Council wanted to straighten Wellington Street. According to the Packet newspaper, the piece of land was “of no value” to the Ordnance Department but was “essential to preserve the uniformity of Wellington Street.”

The Town went ahead and straightened the street over the strenuous objections of the Ordnance Department. Ostensibly, Ordnance claimed that the property was necessary for possible future defensive works. The Packet thought the dispute was caused by the “avarice of one or two self-interested individuals” in Ordnance. In late September 1849, rumours started to circulate that the Home Government in London was about to overturn Bytown’s Act of Incorporation passed by the Canadian Parliament and assented to by the Governor General two years earlier. Fearing this possibility, Councillor Turgeon (a future Mayor of Bytown) proposed repealing the offending By-law that had expropriated the land.

It was to no avail. In late October, the hammer came down. Bytown’s Act of Incorporation was officially disallowed by the British Government in the name of Queen Victoria at the request of the Ordnance Department. Bytown’s politicians were thunderstruck. The news “occasioned no little hub-bub,” said the Packet. “The shock was a dreadful one.” Nobody knew what it meant practically. While “magisterial business” would devolve to the Dalhousie District magistrates, what about other business? Could Bytown pay its bills? What about staffing? The town was described as being in “a bad state” with everything “topsy-turvy.” The Packet fumed at the intrusion of the Home Government in London into a “parish,” i.e. local, matter, and darkly threatened it would be a new argument for the Annexationists (those who wanted the United States to annex Canada).

Map of Ottawa, c. 1840 showing Ordnance land and Wellington Street. Nicholas Sparks, another major landowner, successfully fought the Ordnance Department for the return to him of the Government Reserve Land. This allowed for the development of Sparks street to Sappers’ Bridge by 1849. Taylor, John 1986. “Ottawa, An Illustrated History,” James Lorimer & Company, Toronto.To make matters worse, the Ordnance Department erected a fence across Wellington Street close to Barrick Hill blocking passage of residents to Sappers’ Bridge. Fortunately, there was an alternate route down Sparks Street. The Packet raised its rhetoric called the street closure “a petty act of tyranny inflicted on the habitants of our Town.” It added, “If anything was every calculated to create in the breasts of the inhabitants of this Town an indignant opposition to the British Crown, it is the blocking of one our principal streets.”

Map of Ottawa, c. 1840 showing Ordnance land and Wellington Street. Nicholas Sparks, another major landowner, successfully fought the Ordnance Department for the return to him of the Government Reserve Land. This allowed for the development of Sparks street to Sappers’ Bridge by 1849. Taylor, John 1986. “Ottawa, An Illustrated History,” James Lorimer & Company, Toronto.To make matters worse, the Ordnance Department erected a fence across Wellington Street close to Barrick Hill blocking passage of residents to Sappers’ Bridge. Fortunately, there was an alternate route down Sparks Street. The Packet raised its rhetoric called the street closure “a petty act of tyranny inflicted on the habitants of our Town.” It added, “If anything was every calculated to create in the breasts of the inhabitants of this Town an indignant opposition to the British Crown, it is the blocking of one our principal streets.”

Fortunately, municipal business was quickly regularized with the passage of the Baldwin Act, which allowed towns and cities to incorporate, and the holding of new Bytown Town Council elections in January 1850. With John Scott re-entering municipal politics and his election along with a majority of Reform councillors, Scott was re-elected Mayor of Bytown. Consequently, Scott has the honour of twice being the first Mayor of Bytown. The new Council presented “a humble Petition to the Master General and Board of Ordnance, praying that the Hon. Board may be pleased to grant the use of a space of land opposite Wellington Street to be used for street purposes.” Despite the begging, Ordnance refused to budge.

Residents began to wonder if there was something shady going on. One writer to the Packet in 1851 thought that the Corporation was conspiring in favour of Sparks Street merchants to keep traffic routed down this street rather than negotiating for the re-opening of Wellington Street. Finally, in June 1853, almost four years after the road was closed, Ordnance relented. But its terms were steep: the removal of the fence would be at Bytown’s expense; ownership of the strip of land would remain vested in Her Majesty; the road would be closed on May 1st every year to assert the Queen’s right; Bytown would pay a nominal rent of 5/- per year (5 shillings); no buildings could be erected on this strip of land; and Ordnance reserved the right to resume possession should it feel necessary to do so.

In time, the whole issue became moot when the Ordnance Department dropped its plans to fortify Barrick Hill. On January 1st, 1855, the City of Ottawa, formerly Bytown, was incorporated. One year later, under the Ordnance Lands Transfer Act, ownership of ordnance land in Bytown, and elsewhere, was transferred to the Province of Canada.

Sources:

Canada, Department of the Secretary of State, 1873. Report for the Year Ending 30 June 1873, Appendix A., Department of the Interior, Ordnance Lands Branch, Ottawa.

Durham, Lord, 1839. Report on British North America, Institute of Responsible Government, https://iorg.ca/ressource/lord-durhams-report-on-british-north-america/#.

Elections Canada, 2018. Estimation of Voter Turnout by Age Group and Gender at the 2015 General Election, http://www.elections.ca/content.aspx?section=res&dir=rec/part/estim/42ge&document=p1&lang=e#e1.

Mika, Nick & Helma, 1982. Bytown: The Early Days of Ottawa, Belleville: Mika Publishing Company.

Owens, Tyler, 2016. “A Mayor’s Life: John Scott, First Mayor of Bytown (1824-1857),” Bytown Pamphlet Series, No. 99, Historical Society of Ottawa.

Packet (The) & Weekly Commercial Gazette, 1847. “Prorogation of Parliament,” 31 July.

—————————————————–, 1847. “The Corporation Election.” 18 September.

—————————————————–, 1849. “Bytown Corporation,” 20 September.

—————————————————–, 1849. “The Town of Bytown,” 20 October.

—————————————————–, 1849. “The Ordnance Department And The People Of Bytown,” 13 November.

—————————————————–, 1849. “No Title,” 22 December.

—————————————————–, 1850. “The Elections,” 2 February.

—————————————————–, 1850. “Vote By Ballot, Etc.” 23 February.

—————————————————–, 1850. “Town Council Proceedings,” 23 February.

—————————————————–, 1851. “Queries Addressed To No One In Particular,” 21 June.

—————————————————–, 1853. “No Title,” 11 June.

Shortt, Adam & Doughty, A.G. Sir, 1914. Canada and its Provinces : a history of the Canadian people and their institutions, Volume 18, Toronto: Glasgow, Brook & Company.

Taylor, John H. 1986. Ottawa: An Illustrated History, Toronto: James Lorimer & Company.

Whan, Christopher, 2018, “Voter turnout for Ottawa’s municipal elections up from 2014,” Global News, 23 October.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

University of Ottawa

26 September 1848

The University of Ottawa was founded on September 26, 1848, as the College of Bytown by Bishop Joseph Bruno Guigues as a bilingual Roman Catholic institution aiming to bridge the gap between Protestants and Catholics as well as anglophone and francophone populations. The bilingual college originally sat in a wooden building (now the former La Salle academy) beside the Notre Dame Cathedral on Sussex Drive and served the educational needs of Ottawa’s population and the Canadian Diocesan and Catholic clergies. The college was incorporated by the Provincial Parliament in 1849 and was moved twice in 1852 before its final move to its current location in Sandy Hill in 1856 due to increase in need for space. It was Louis-Theodore Besserer, a Quebec businessman, notary and political figure who sold a substantial portion of his estate to the college. The university now sat in a stone building to the south of Séraphin Marion and had classrooms and dormitories to accommodate the students living in residence.

Though Bishop Guigues sought funds from the government and land use authorization, the early years of the college was marked with financial difficulties and questioned the college’s existence. Bishop Guigues managed to receive a government funding of £300 in 1857 (roughly $35,000 today) while Regiopolis College, Kingston (a college that focused on education only in English) was awarded £500 in 1847 and continued to receive funding each following year. This made the Diocese of Ottawa fall into debt and the college was eventually sold to the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate in 1856. After the Oblates took over, the college was integrated into the foreign resources of the French order and had eight professors and ninety students which increased to 160 students three years later. The College of Bytown was officially renamed to College of Ottawa in 1861 and was offered university status in August 1866 with the first graduation ceremony taking place in 1890.

Father Guigues’ bilingual mission was continued by Father Joseph-Henri Tabaret who was dedicated to the growth and future university. In 1874, an increasing number of anglophone students and all courses being taught in English only excluding French literature and religion that were taught in French threatened the future of bilingual education in the university. Bilingualism slowly began to be restored in 1894 when the Oblate students pressured Rector Father Henri Constantineau to bring back French education which heightened the Franco-Irish tensions and was resolved when all the Irish Oblate professors, the loudest advocates for English education resigned in 1915.

On the other hand, Father Tabaret pushed towards an expansion that saw over 300 students enrolled by 1886 and made investments into sports by establishing the football team in 1881 and an Athletic Club in 1885. A highly decorated chapel that could seat a 1,000 people was added in 1887. The university also saw the creation of an English Debating Society in 1880, a first of its kind at that time with its French equivalent of Société des débats français followed in 1887. The tremendous growth during Father Tabaret’s period earned the university an ecclesiastic charter issued by the Pope in 1889. Affiliation with other colleges and universities in Canada was made possible through legislation passed in 1891, though it remained unused for the next two decades. At this point the university had just over 400 (all male) students, most in high school level (as the university offered both secondary and tertiary education) and fifty professors.

1903 fire - uOttawa ArchivesIn the middle of difficulties (Franco-Irish conflicts and the Ontario Schools Question) that shook the university in the early 20th century, on December 2, 1903, a fire destroyed the college’s main building, costing three lives and the lost of several historical records. New York Architect A. O. Von Herbulis was appointed to design the Tabaret Hall in a Greek Neo-classical style which replaced the main building, and it was opened in 1905. The new building was named after Father Tabaret to recognize his contributions to the university over 30 years of his tenure.

1903 fire - uOttawa ArchivesIn the middle of difficulties (Franco-Irish conflicts and the Ontario Schools Question) that shook the university in the early 20th century, on December 2, 1903, a fire destroyed the college’s main building, costing three lives and the lost of several historical records. New York Architect A. O. Von Herbulis was appointed to design the Tabaret Hall in a Greek Neo-classical style which replaced the main building, and it was opened in 1905. The new building was named after Father Tabaret to recognize his contributions to the university over 30 years of his tenure.

Tabaret Hall circa 1905 - uOttawa Archives

Tabaret Hall circa 1905 - uOttawa Archives

Though World Wars did not impact the university significantly, it should be noted that interwar years were important and contributed to the university’s growth given that this was the only Catholic institution offering education in French outside of Quebec in Canada. This paved way for the affiliation of twenty-four colleges and convents (many being francophone) in Ontario and the Western provinces with the university. Women were allowed to register into courses in 1919 and between 1922 and 1936, the university saw further expansions with the establishment of school for teacher training, nursing, and faculty of canon law and arts. With this rapid growth, the university rewrote its civil charter according to the provincial legislations in 1933 and was renamed as the “University of Ottawa”. The pontifical charter was also rewritten to meet the Pius XI’s Apostolic Constitution’s requirements and was approved by Rome in 1934. The economic boom after the end of the Second World War led to the creation of nine faculties and four schools by 1965.

In 1959, the university acquired expropriation powers to expand the Sandy Hill campus to meet the growing enrollments. This caused the university to fall into deficit every year in the 1960s and it began talks with the provincial government with the province demanding the Oblates to pass over the power to the government.

“The year 1965 marked the end of one era and the beginning of another.”

- Saint Paul University History (n.d.). Retrieved from ustpaul.ca/en/about-spu-history_493_360.htm

After rigorous negotiations with the provincial government, the Oblates handed over control to the province in 1965. The old university came to be called Saint Paul University and the province formed a new university which was named as the University of Ottawa according to the University of Ottawa Act, 1965. They became a federated institution and share the faculties. Roger Guidon who was appointed as the Rector of the old university in 1964 remained Rector of the new university until 1984. During his tenure, he modernized the university, hired substantial numbers of lay faculty, support staff and women. The number of professors had increased from 300 in 1965 to 1000 in 1990. Financial aid from government also helped further the university’s expansion well into 2000. Regarded as the largest bilingual university in North America, today it comprises of four campuses covering 42.5 hectares with more than 40,000 students and 5,000 employees and offers over 450 programs in 10 faculties.

Sources

About uOttawa. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.uottawa.ca/about/

Jones, D. (2017, May 12). 8. Académie de-la-salle. Retrieved from https://heritageottawa.org/fr/50years/la-salle-academy

Saint Paul University History. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://ustpaul.ca/en/about-spu-history_493_360.htm

Strömbergsson-Denora, A. (2012, February 8). University of Ottawa. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/university-of-ottawa

The University of Ottawa. (2019, July 20). Retrieved from https://www.ash-acs.ca/history/the-university-of-ottawa/

Image Credits

Strömbergsson-Denora, A. (2012, February 8). University of Ottawa. Retrieved from https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/university-of-ottawa

The archives turns 50. (2017, February 27). Retrieved from https://www.uottawa.ca/gazette/en/news/archives-turns-50

Story written by Nivethini Jekku Einkaran, an architectural conservation graduate from Carleton University. She has an undergraduate degree in architecture from India and is a registered architect in India where she worked as a junior architect before moving to Canada. Nivethini is a volunteer with The History Society of Ottawa.

Élisabeth Bruyère: Caring and Daring Bytown Pioneer

Venerable Élisabeth Bruyère — 175th Anniversary

Gravely needed in Bytown, Élisabeth Bruyère (aged 26) and her small entourage of young Grey Nuns bravely journeyed the frozen Ottawa River by sleigh from Montreal.

Within three months of their arrival in rugged Bytown, Mother Bruyère and her group had founded a school, a general hospital, a home for the aged and an orphanage; and within another two years Mother Bruyère and the sisters would defy the risk of deadly contagion and tend to the sick as Bytown found itself in the midst of a severe typhus epidemic.

Mother Élisabeth Bruyère was a woman with a caring and compassionate heart and of daring faith. She founded the first congregation of religious women in the Archdiocese of Ottawa, the Sisters of Charity of Ottawa (also called Grey Nuns of the Cross until 1968).

Élisabeth Bruyère was born in L’Assomption, Que., on March 19, 1918. Her father died when she was six years old. She spent her childhood in Montreal where her mother became a household servant to earn a living for her family. Élisabeth was educated by the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre Dame.

Spiritual Daughter of Marguerite d’Youville

In 1839, Élisabeth, attracted by Saint Marguerite d’Youville’s charisma, entered the Congregation of the Grey Nuns of Montreal. In 1841, she pronounced her vows of religion; for the next four years, she was given the responsibility of educating 40 young orphan girls.

Her remarkable qualities were admired by her Superiors who chose her as the founding Superior of the mission in Bytown.

Arrival in Bytown: Founder by the Will of God

Astonished to receive this assignment, Sister Élisabeth Bruyère saw in this nomination the expression of God’s will. On February 19, 1845, she left with three professed Sisters, 1 postulant and 1 aspirant. On February 20, 1845, they arrived in Bytown where the caring and daring Bytown pioneer’s mission of love, service and compassion began.

Absolute Trust in Providence

Grace nurtured faith which led Mother Bruyère to seek God’s will. Her unconditional trust in Divine Providence opened her hands to all those in need. Pain never failed to resonate in Mother Bruyère’s caring heart as she reached out to everyone the Lord placed on her path.

Heroism of Charity

Mother Bruyère’s daring faith never failed her. The Sisters’ accomplishments went far beyond the imaginable, given their meagre resources. Barely 3 months after the Sisters’ arrival, the first bilingual school in Eastern Ontario, a General Hospital (today Bruyère Continuing Care), a Home for the Aged, an orphanage and a home for foundlings came into existence.

Mother Bruyère was a woman of heroic charity. During the typhus epidemic of 1847, 17 of the 22 Sisters contracted the disease while caring for the Irish immigrants, but none of them died. The same heroism was manifested during a smallpox epidemic in 1871.

No one wanted to care for the victims; the Sisters secretly set up a “lazaretto” in the convent yard. For over two years, 5 Sisters and 2 aides lived in isolation to care for the contagious patients.

Specific Charism

Alongside Sister Rachelle Watier, Superior General of the Sisters of Charity, Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson declares Mother Élisabeth Bruyère Day on February 25, 2020, during a ceremony at the Bruyère Hospital in Lowertown. Bruyère’s arrival in Bytown in 1845 marked the beginning of organized healthcare in the city.Spiritual daughter of Saint Marguerite d’Youville, “Mother of Universal Charity”, Mother Bruyère sowed the seed of this legacy in the hostile soil of Bytown. Incarnating Marguerite d’Youville’s charism of compassion for the poor, she added a new dimension: education, a priority need in Bytown. The Congregation’s distinctive character gradually became evident: on the one hand service to the poor, the forsaken, the suffering; and on the other hand, education adapted to all levels of society and to all human needs.

Alongside Sister Rachelle Watier, Superior General of the Sisters of Charity, Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson declares Mother Élisabeth Bruyère Day on February 25, 2020, during a ceremony at the Bruyère Hospital in Lowertown. Bruyère’s arrival in Bytown in 1845 marked the beginning of organized healthcare in the city.Spiritual daughter of Saint Marguerite d’Youville, “Mother of Universal Charity”, Mother Bruyère sowed the seed of this legacy in the hostile soil of Bytown. Incarnating Marguerite d’Youville’s charism of compassion for the poor, she added a new dimension: education, a priority need in Bytown. The Congregation’s distinctive character gradually became evident: on the one hand service to the poor, the forsaken, the suffering; and on the other hand, education adapted to all levels of society and to all human needs.

A Caring and Daring Bytown Pioneer

Mother Bruyère’s pastoral initiatives responded to the urgent needs discerned in Bytown: classes for the children and for mothers, home visits to the poor and the sick, assistance to the dying. During the epidemic, she did not hesitate to bury the dead. She paid close attention to the repentant wayward girls, opened St Raphael’s house for immigrants and regularly visited prisoners. Sensitive to the spiritual needs of the Church and to the social needs of the citizens of Bytown and beyond, she opened new houses, not only in Ontario and Quebec, but also in the U.S. so as to provide schools for the Franco-American population.

Mission Well Accomplished

For 31 years Mother Bruyère was a witness to the Father’s tender love while also bearing the responsibility for her young Congregation. At the end of her life, she said: “All was blessed by God because all has been accomplished in conformity with His Holy Will.” (Dec 24, 1875). Mother Bruyère entered eternal rest on April 5, 1876; she was 58 years old.

The Sisters of Charity of Ottawa Continue her Mission

The seed planted by Mother Bruyère in Bytown has grown to full stature and the small community of 1845 has extended its branches widely. Faithful to the spirit of their caring and daring Founder, the Sisters of Charity of Ottawa continue her mission, her charism and her spirituality.

They join their charism of compassion to the evangelization mission of the Church, happy to be witnesses of God’s tenderness and messengers of hope and salvation. Daughters of the Church, they go to the peripheries to share the Good News in Canada, the U.S., Lesotho, Republic of South Africa, Malawi, Zambia, Brazil and Japan.

Conclusion

Mother Bruyère’s life was a true quest for God. She entrusted herself fully to the Providence of God, the Eternal Father. The process toward Mother Bruyère’s Canonization opened in 1978. Her entire life of service and of compassion was a function of her faith, hope and love of God. She was found to demonstrate these virtues in a heroic manner. On April 14, 2018, His Holiness, Pope Francis declared the Servant of God, Mother Élisabeth Bruyère, to be Venerable, thereby opening the path to her eventual Beatification and Canonization … in God’s good time. Venerable Mother Élisabeth Bruyère, intercede for us.

Bytown Museum’s Roots with the Historical Society of Ottawa

The guest speaker for the first HSO meeting of 2020 is familiar to many who have a love of Ottawa’s past. As the executive director of the Bytown Museum, Robin Etherington has been an enthusiastic promoter of culture and heritage in Ottawa for over 20 years. Robin has been the executive director of Bytown Museum since 2012.

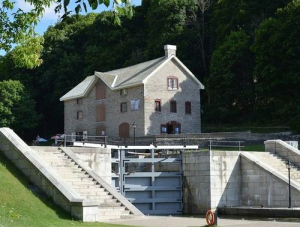

The Bytown Museum is located in the oldest building in the city. Of course, the museum wasn’t built as a museum. The stone structure was initially a “commissariat” and its construction was supervised by none other than Lieutenant-Colonel John By.

Built as early as 1826 and located near the entrance lock of the Rideau Canal, today’s Bytown Museum initially served as the operational nerve centre during construction of the canal (the Commissariat Department of the British military oversaw the supply of food and provisions) and then as the administrative headquarters of the canal once it opened in May 1832.

Robin EtheringtonRobin noted that By was more than just a canal builder. He was as much an urban planner. He laid out the early streets of Lowertown and also what is now the Parliamentary Precinct. She also noted that By purchased land in Ottawa to reassure others that a thriving community would soon grow here.

Robin EtheringtonRobin noted that By was more than just a canal builder. He was as much an urban planner. He laid out the early streets of Lowertown and also what is now the Parliamentary Precinct. She also noted that By purchased land in Ottawa to reassure others that a thriving community would soon grow here.

After talking about the early days of the museum building, Robin discussed the formation of the organization that ran the Bytown Museum for 105 years. In 1898, thirty-one Ottawa ladies formed the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa (WCHSO) to promote a better understanding of the city’s history.

The society was limited at the time to holding community meetings, but in 1917 an opportunity arose to expand the society’s scope. In 1910, the City of Ottawa had moved out of the registry office on Nicholas Street that it had occupied since 1871.

After the building was left vacant for seven years, the WCHSO proposed to establish a museum there to display artifacts that the ladies had collected over the years, with their own money.

In 1952, the Bytown Museum moved to its present location. In 1955, the men of Ottawa were invited to join the WCHSO. With the “W” now redundant, the name of the organization was changed in 1956 to the now-familiar Historical Society of Ottawa (HSO).

HSO continued to manage the museum and to hold regular meetings for members and the public until 2003, when the decision was made to transfer the Bytown Museum to a separate not-for-profit organization.

It was at this time that HSO “lost” its museum, but the association between HSO and Bytown Museum has remained strong. As such, Robin was less a “guest” speaker at our Jan. 15 meeting than she is friend, supporter and member of HSO.

Following her review of the history of the museum, Robin talked about something that is near and dear to her: the museum’s future. It’s not all good news. Being part of the Parliamentary Precinct’s independent, and rapidly aging power supply system, blackouts have become an all-too-frequent occurrence. Rockslides are a constant threat, as natural geological dynamics take a slow toll on Parliament Hill, which overlooks the museum.

Located near the bottom of a hill so steep that the lay of land forced Colonel By to build eight locks, universal accessibility to the museum has been an ongoing problem. And let’s not forget that the museum building itself will reach the beginning of its third century in 2026.

But there is a lot of good news, too. Robin observed that, “today is tomorrow’s history” and that was inspiration for Bytown Museum’s most recent exhibit, 100 Years of Youth in Ottawa.

This is a collection of photographs of young Ottawans from 1917 to 2017, showing how the many activities that youth have engaged in through the years have changed . . . and how many remain the same. All photos for the exhibit were selected and researched by the museum’s Youth Council.

New for 2020 is an exhibit entitled A Local Canvas: Paintings from the Bytown Museum Collection, in which the museum curates an eclectic assortment of paintings from an equally curious list of collectors and artists. The items chosen for the display were selected during the museum’s continuing project to capture digital images of its collection.

Burnstown Publishing.The last word for the evening went to Bruce MacGregor, who is author of Capital Recollections: A Baby Boomer Growing Up in Ottawa. Bruce has been a resident of Ottawa since 1952.

Burnstown Publishing.The last word for the evening went to Bruce MacGregor, who is author of Capital Recollections: A Baby Boomer Growing Up in Ottawa. Bruce has been a resident of Ottawa since 1952.

He taught English at Glebe Collegiate for 30 years. Capital Recollections is his first work of non-fiction. Bruce read an excerpt from his new book about a not-yet famous Canadian who happened to be at a local arena in 1963.

You’ll have to buy the book to find out who. It’s available for $20 via burnstownpublishing.com.

Ottawa LRT Art Celebrates HSO’s 1898 Origin

An elaborate public art installation at the new Lyon Street light rail transit station in downtown Ottawa is sharing the origin story of the HSO with thousands of daily commuters.

The undulating stainless steel sculpture commemorates and celebrates the 1898 founding of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa — later opened to men and renamed the Historical Society of Ottawa — and incorporates the entire 5,000-word text of a society-published pamphlet about the city’s early history.

Individualized silhouettes representing the 32 women who were present at the first meeting of the society in June 1898 adorn the top of the two-metre tall sculpture, which is fully reproduced in French.

The artwork covers a 14 x 4 metre area along a main public concourse, even snaking around one of the station’s support pillars.

The title of the artwork, With Words As Their Actions, is incorporated in a message that appears in large letters across the top of the sculpture: “These Women Built Bytown And Ottawa With Words As Their Actions.”

Along the bottom edge of the steel curtain of text, another message in large letters details the historic gathering that brought the society into existence more than 120 years ago: “Lady Edgar invited thirty-one ladies to her drawing room on 3 June 1898 to consider the formation of a Women’s Historical Society.”

The same messages appear in the French-language half of the art-work, titled Par la Force des Mots.

In March 1950, the Ottawa Citizen covered the appointment of the directors of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa, which would soon admit male members and rename itself the Historical Society of Ottawa. She added: “With Words as Their Actions pays tribute to the women who kept Bytown alive long after its transformation into Ottawa . . . Here were these women who were saying, ‘We are going to start losing history if we don’t start saving it.’ ”

In March 1950, the Ottawa Citizen covered the appointment of the directors of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa, which would soon admit male members and rename itself the Historical Society of Ottawa. She added: “With Words as Their Actions pays tribute to the women who kept Bytown alive long after its transformation into Ottawa . . . Here were these women who were saying, ‘We are going to start losing history if we don’t start saving it.’ ”

The installation was created by the Toronto-based firm PLANT Architect Inc., which was awarded the commission after a public art competition held in 2015. The company previously created the Canadian Firefighters Memorial on LeBreton Flats.

As part of the contract for construction of the LRT system, one per cent of the overall construction cost was set aside for displays of artwork at each of the 13 light rail stations.

PLANT Architect’s tribute to the founders of the WCHSO and their work as preservers and promoters of the city’s history cost $200,000.

The silhouetted figures are arrayed in pairs of women facing each other, “representing the society’s founders gathered in conversation” and “passing their knowledge from one another, and to the viewer,” the creators explained.

“This historical society was Ottawa’s first, and from the late 19th century until after World War II, all of its members were female,” PLANT partner Lisa Rapoport, the project’s design lead, told the Daily Commercial News in an interview earlier this year. “While their husbands were building with wood, stone, rail ties and financial capital, the society’s members were building an edifice of words and stories.”

Society member Anne Forbes Dewar, top left, authored a 1954 paper titled “ The Last Days of Bytown ,” republished by the HSO in 1989. The entire 5,000-word text of the pamphlet — in English and French — has been incorporated in a steel sculpture installed at the Lyon LRT station that celebrates the role of the WCHSO in preserving and promoting Ottawa’s history.

Society member Anne Forbes Dewar, top left, authored a 1954 paper titled “ The Last Days of Bytown ,” republished by the HSO in 1989. The entire 5,000-word text of the pamphlet — in English and French — has been incorporated in a steel sculpture installed at the Lyon LRT station that celebrates the role of the WCHSO in preserving and promoting Ottawa’s history.

The design, states a PLANT over-view of the project, “celebrates women as keepers of history — and in particular, the 32 women who, in 1898, founded the Ottawa chapter of the Women’s Canadian Historical Society (now the Historical Society of Ottawa).”

The bulk of the sculpture is comprised of alternating English and French lines of text from a presentation titled “The Last Days of By-town,” written in 1954 by society member Anne Forbes Dewar and published in 1989 as No. 32 of the HSO’s Bytown Pamphlet series.

There are now more than 100 published papers in the Bytown Pamphlet series, most of which are available for download at the HSO website — including Dewar’s essay — and all of which are available through the Ottawa Public Library. In a brief introduction to the Dewar pamphlet, the author was described as “an early and active member” of the WCHSO, which she also served as a board member: “She loved history and was extremely knowledgeable and well-read, especially about local history.”

Dewar, who died in 1964, had prepared her 1954 research paper by poring over old Ottawa newspapers, consulting local history books and tapping a variety of other sources to paint a portrait of Bytown as it exist- ed 100 years earlier, in 1854 — the year before the city was officially renamed Ottawa on Jan. 1, 1855.

“This is an amazing document,” Rapoport said in the DCN interview, referring to Dewar’s painstaking reconstruction of 1854 Bytown, on the eve the change to the City of Ottawa. “We thought it would be great for everybody to read it.”

Among the most noteworthy passages in Dewar’s pamphlet — especially now that her words have been laser-cut in steel into a permanent artwork at a downtown train station — were her observations about the December 1854 inauguration of the Bytown and Prescott Railway.

It was a landmark event in Ottawa history and marks the birth of rail transportation in the city.

In recounting the arrival in By-town of the first-ever trainload of passengers from Prescott on Christmas Day 1854, Dewar commented that a celebratory banquet following the event “provided the appropriate jollification.”

She then offered further thoughts on the railway’s launch that should offer some solace to present-day city officials who have faced sharp criticism over the LRT’s bumpy rollout throughout the fall and early winter of 2019.

“The railway had been a great accomplishment,” Dewar wrote of the launch of train service in 1854. “As might have been expected in the early days of operation, unlooked for difficulties arose . . . (but) before long the Bytown and Prescott was generally acknowledged to be the safest and smoothest railway line on the American continent.”

The silhouettes of Lady Matilda Ridout Elgar, host of the inaugural meeting of the WCHSO, and found- ing member Gertrude Kenny appear to engage in conversation atop the massive art installation at the Lyon Street LRT station.

The silhouettes of Lady Matilda Ridout Elgar, host of the inaugural meeting of the WCHSO, and found- ing member Gertrude Kenny appear to engage in conversation atop the massive art installation at the Lyon Street LRT station.

Photo: Randy BoswellSeveral HSO members, including past president George Neville and former board members Don Baxter and Bryan Cook, were consulted during the design of the Lyon Station artwork.

The impressive LRT tribute to the matriarchs of the present Historical Society of Ottawa joins a host of other landmarks around the capital attesting to the HSO’s enduring impact since its founding near the end of the 19th century.

These include the Bytown Museum beside the Rideau Canal head-locks and the statue of Lt.-Col. John By in Major’s Hill Park, both of which were society initiatives.

“No longer will only society members be familiar with our beginnings as the WCHSO,” said Karen Lynn Ouellette, president of the Historical Society of Ottawa. “This stunning artistic installation invites all LRT travellers to learn about our society’s contributions to saving and sharing our local heritage.”

She added: “I am so proud to be part of this legacy of women helping to preserve our city’s history.”

The curving, curtain-like sculpture (below), a tribute to the female founders of the historical society, invites passersby to sample bits of early Ottawa history inscribed in steel.

The curving, curtain-like sculpture (below), a tribute to the female founders of the historical society, invites passersby to sample bits of early Ottawa history inscribed in steel.

Photo Randy Boswell