Part Two: Logging

Upon their arrival to Canada in 1830, Irish immigrants, Roderick Ryan and John Egan, entered the lumber trade. A year later, they were the subject of a complaint made by Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) chief trader, John Silverright, to the company’s director, Sir George Simpson. Silverright’s grievance was that the timber men were disturbing trade at the mouth of the Dumoine. [[1]]

It was prior to the arrival of Ryan and Egan, however, that saw the development of several key lumber trade innovations that made operations on the Dumoine feasible. First, in 1806, Philemon Wright (founder of Wrights Town) piloted a square timber raft from the town to the port of Quebec, establishing the logistics for how Ottawa Valley timber could be transported by river. By 1826, Wright’s son, Ruggles Wright, built the first timber crib slide there hastening everyone’s journey to Quebec. [[2]]Londoner merchants, George and William Hamilton Sr, relocated their timber business from Britain to Quebec as their timber source from the Baltic countries had been blocked by Napoleon Bonaparte. In 1809, the Hamiltons acquired a mill at the village of Hawkesbury. Within four decades, under the name The Hamilton Brothers (later named Hawkesbury Lumber Company), their sons would replace John Egan and run the largest timber operation in the Dumoine Valley.

Roderick established a base of operations across from the mouth of the Dumoine at the village of Rockcliffe (today called Stonecliffe) because of a colonization/supply road being built from Pembroke to Mattawa. By 1840, Ryan had begun cutting up from the mouth four kilometres to a chute now named after him. Egan’s crews, led by his chief engineer, William Moffat (son of one of the founders of Pembroke), were cutting lumber above Ryan’s Chute and up the west branch of the Dumoine by 1845. Within twenty years, other lumber kings, such as Joseph Aumond, Benjamin Moore, the Cullin Brothers, and the Hamilton Brothers, joined Egan and Ryan. [[3]]

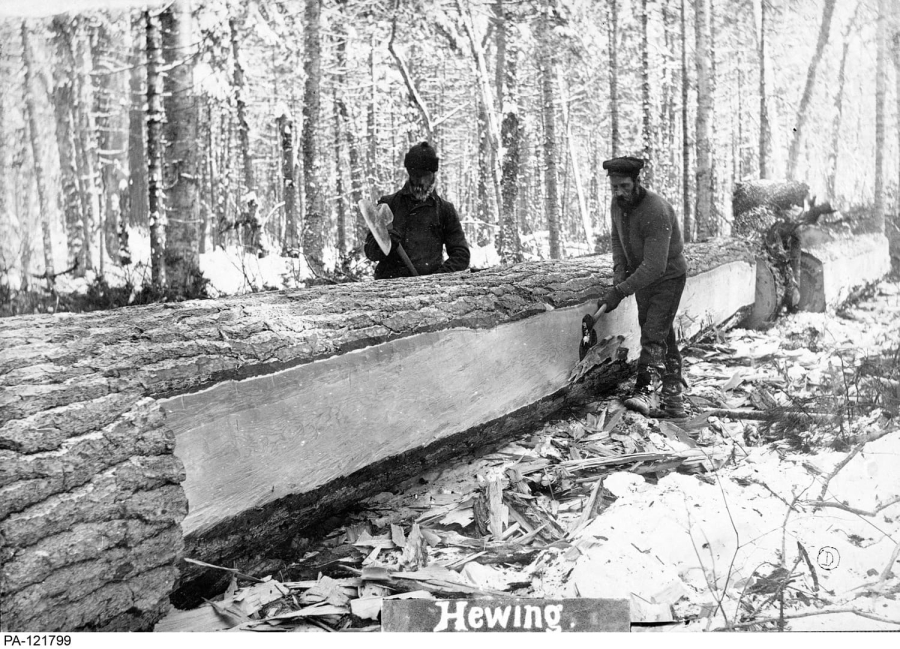

A large log boom at the mouth of the Dumoine collected the logs from all the companies. From there, the individual companies formed their hewn property into twenty-six-foot-wide cribs to fit down the slides, then combined these cribs into giant rafts and hired special crews to pilot them on the two-month journey to Quebec City. The logging business was built on a strategy of first cutting the timber closest to the Ottawa River, then proceeding up the tributaries. Each company’s specialized timber appraisers called timber cruisers, blazed the trails to find the best timber stands and identify where to build the winter shanties. Building a supply road to haul food and materials for the men and horses into the shanty camps was a key part of this strategy.

By the 1850’s, the flood of companies buying the newly surveyed timber limits in the watershed was unstoppable. Together they all formed the Dumoine Boom and Slide Company to engineer the river at bottlenecks to efficiently run logs down to their shared boom at the mouth. This extensive cutting required an army of support, farmers pulling sleighs of food and equipment into the shanty camps to keep the men and horses fed and equipped. In 1860, surveyor David Sinclair, credited William Moffat, who at the time was working with the Dumoine Boom and Slide Company, with building a beautiful wagon road from the Ottawa River to the Grande Chute (now called the Dumoine Tote Trail). [[4]] Moffat also built the first version of the Grande Chute timber slide, a 400-foot single slide clinging to the west short beginning at Grande Chute Falls.

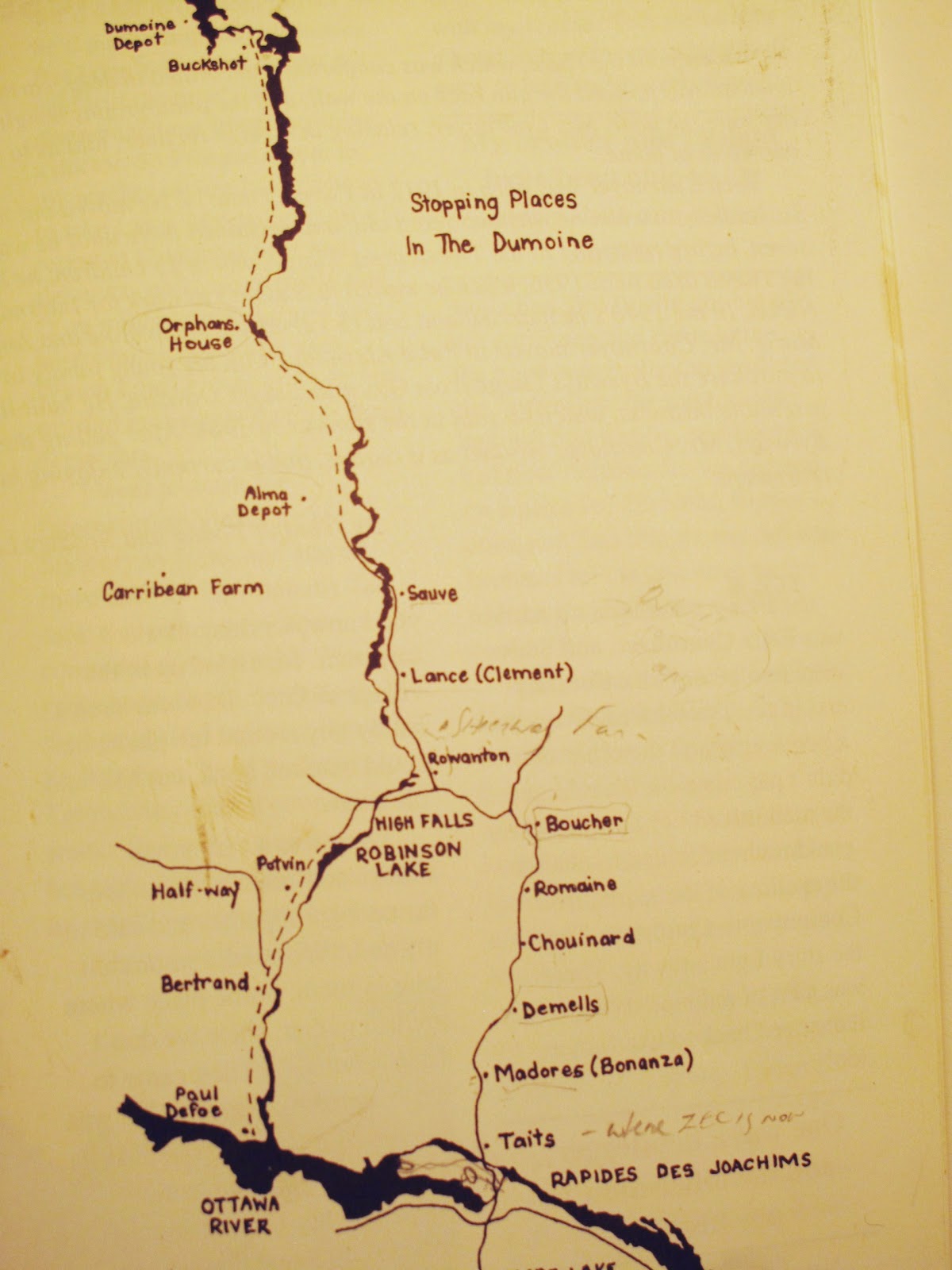

It has been calculated that a winter shanty required three pounds of supplies brought in for every board foot of lumber taken out and there were hundreds of thousands of board feet cut in the Dumoine Valley. [[5]] This constant flow of goods going up and logs coming down the Dumoine created a need for extensive infrastructure of wagon roads with stopping places every ten miles to house the teams and drivers. The teams were only capable of travelling that far each day, pulling their 2000-pound load through the snow. [[6]]

Historic map of stopping places along the Dumoine - Tamarack Magazine Issue 3 / Bill Paterson

Historic map of stopping places along the Dumoine - Tamarack Magazine Issue 3 / Bill Paterson

At Rowanton, the Hamilton Brothers, and Booth and Eddy at Lac Dumoine, built large depot farms staffed with black smiths and labourers where they stockpiled supplies, grew feed, raised livestock, and maintained sleighs, wagons and tools. These farms work with family homesteads, called Stopping Places, which were located ten miles apart to accommodate teamsters who delivered supplies in the winter.

The creeks in the watershed required the building of dams, slides, and rock walls to control the water to flush the logs down to the Dumoine each spring. The longest single log slide in the world, at 3,364 feet, was built in 1871 by the government that was around Grande Chute area to replace Moffat’s original slide. It was only used to transport squared timbers for a fee of .15c each. The last squared timbers were cut around 1920 and the slide was dismantled shortly after that for its timber value.

New mills were built at Chaudière Falls in the late 1850’s. These mills demanded thousands of smaller sixteen-foot saw logs to produce lumber. The saw logs were easier to cut and drive down the Dumoine than the squared forty-foot giants. With the closer Ottawa destination, versus the squared timbers bound for Quebec City, the saw logs could be moved by water to the mills quicker, therefore being cut further north, well beyond Lac Dumoine. JR Booth, along with EB Eddy and Bronson & Weston, were the three largest operators of the second generation of lumbermen in 1880. Canadian invented steam powered boats called Alligators replaced hand or horse powered towing methods. The remains of two alligator boats can still be viewed from the shore of Lac Laforge, located just below Lac Dumoine. From the catch boom at the mouth of the Dumoine, the saw logs were towed to the mills. A new lumber company cooperative, the Upper Ottawa Improvement Company (ICO), was created in 1868 to tow every company’s logs to the mills in Arnprior and Ottawa. Each log was stamped with the owner’s brand. By 1900, another type of log, the four-foot pulp log, was added to the Dumoine river drive. EB Eddy and Booth lumber companies both opened pulp and paper mills at Chaudière Falls beginning in the 1890’s. The last river drive on the Dumoine was April 1961. The ICO continued to tow Dumoine logs trucked out to the Ottawa River, until 1990 when all log drives were stopped due to environmental damage.

Dumoine Club members at Stonecliffe Station (1938) - Private collection D. Charbonneau, Stonecliffe, OntarioThe logging era overlapped with new forms of recreation, including outdoor hunting and fishing clubs, and canoe tripping camps. In 1892, the Quebec government allowed groups of mostly well-off gentlemen to apply for large private fishing and hunting leases and establish a lodge base camp. Many old lumber camps were repurposed as club lodges. There were five such leases in the Dumoine watershed, accessible mostly by foot or horse via the original logging tote roads. The Dumoine Rod and Gun Club still stands as a fine example of this era. By the 1940’s, there were a dozen camps running trips, and today, some of these original camps are still in existence and over a thousand independent canoeists paddle the Dumoine each season. [[7]]

Dumoine Club members at Stonecliffe Station (1938) - Private collection D. Charbonneau, Stonecliffe, OntarioThe logging era overlapped with new forms of recreation, including outdoor hunting and fishing clubs, and canoe tripping camps. In 1892, the Quebec government allowed groups of mostly well-off gentlemen to apply for large private fishing and hunting leases and establish a lodge base camp. Many old lumber camps were repurposed as club lodges. There were five such leases in the Dumoine watershed, accessible mostly by foot or horse via the original logging tote roads. The Dumoine Rod and Gun Club still stands as a fine example of this era. By the 1940’s, there were a dozen camps running trips, and today, some of these original camps are still in existence and over a thousand independent canoeists paddle the Dumoine each season. [[7]]

Wallace A Schaber

I am not a professional historian or Anishinabe expert. I am a collector of maps, stories, and artifacts about the Dumoine based on fifty years of guiding there by canoe, ski and foot. My book, Last of the Wild Rivers (2016) is available as an e-book online.

Friends of the Dumoine

In 2016, concerned Dumoine guides and travellers formed Friends of Dumoine to keep the rivers portages and campsites clean.

Mission Statement

“To champion conservation of the Dumoine watershed, promote non- mechanized recreation and strengthen knowledge of its natural environment and human history.”

Our major achievement to date is the re-opening and interpretation of the old Anishinabe portages that existed for centuries and linking them to the Dumoine tote road used by the lumber industry beginning in 1840. This hiking trail is now open from the Ottawa River to Grande Chute as a twenty-six-kilometre hiking-skiing trail www.sentierdumoine.ca . A visitor centre at Grande Chute complete with historic maps and artifacts is located at the northern gateway.

Please join us on the trail or virtually online to explore Canada's history and protect it. For more information about how to volunteer or donate write This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

Friends of the Dumoine would like to thank our partners in helping to make this project a reality.

CPAWS Ottawa Valley

Zec Dumoine

Wolf Lake First Nation

Suggested Further Readings

Barrett, Harry B. and Clarence F. Coons. Alligators of the North. Nature Heritage Books: Toronto, 2010.

Lee, David. Lumber Kings and Shantymen. James Lorimer and Company Ltd: Toronto, 2006.

MacKay, Donald. The Lumberjacks. McGraw-Hill Ryerson Ltd: Toronto, 1976.

Reid, Richard ed. The Upper Ottawa Valley to 1855. Carleton University Press: Ottawa, 1990.

Whitton, Charlotte. A Hundred Years A -Fellin: Some Passages from the Timber Saga of the Ottawa in the Century in Which the Gillies Have Been Cutting in the Valley 1842-1942. The Runge Press Limited: Ottawa, 1974.

[[1]] HBC extended goods in the fall on credit to the Anishinabe traders and expected that all furs would come to them in the spring to pay off the credit. Lumbermen interrupted this tradition by doing the trapping themselves, destroying habitat and trading more aggressively with the local trappers. Elaine Allan Mitchell, Fort Timiskaming and the Fur Trade (University of Toronto Press, 1977).

[[2]] Previously rafts needed to be completely disassembled at each rapid. By 1844, the Government of Canada had built similar slides around each major rapids from the Dumoine to Ottawa, meaning timber cribs could be run down a slide saving time and lives. Whitton, A Hundred Years A -Fellin.

[[3]] All these were timbermen from Aylmer and Ottawa, and members of the Ottawa River Lumber Association. Reid, The Upper Ottawa Valley.

[[4]] See www.sentierdumoine.ca .