Super User

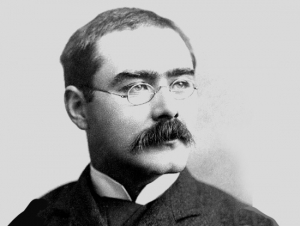

The Empire's Poet Comes to Ottawa

19 October 1907

Most people only know Rudyard Kipling as the author of The Jungle Book, the beloved tale of Mowgli, the “man-cub,” who was raised by wolves in nineteenth-century India and battled Shere Khan, the evil tiger, with help from Baloo, the bear, and the elephants. The story has been made into many movies and television shows, most notably by Walt Disney Pictures whose 2016 production went on to gross almost US$1 billion. The film was itself a remake of a 1967 animated film by the same company.

But Kipling is the author of far more—hundreds of poems, sonnets, short stories, and books. He was called the Poet of the British Empire, and won the 1907 Nobel Prize for Literature. Kipling was vastly popular in his day, as much, or more so, than Shakespeare. One contemporary American author remarked that “the literateurs of the world are divided into two classes—‘Rudyard Kipling’ and the other fellows.” Kipling’s novel Kim, the story of an Irish solider on northern Indian frontier set amidst the political intrigues of the “Great Game” between Britain and Russia, is ranked among the top English-language novels of the twentieth century. His classic children’s stories, including such tales as The Elephant Child, How the Leopard got his Spots, and Rikki-Tikki-Tavi, the adventures of a mongoose, continue to be enjoyed around the world. As a youngster, I was entranced by these stories as were my children a generation later. I also remember having to memorize in school his poem A Smuggler’s Song. Fifty years later, I can still recall it—“If you wake at midnight, and hear a horse’s feet, Don’t go drawing back the blind, or looking in the street, Them that asks no questions isn’t told a lie. Watch the wall my darling as the gentlemen go by.”

However, Kipling’s reputation and legacy are ambiguous and controversial. While many of his stories have stood the test of time, and expressions he coined have entered the English language, he held views that are today either outdated, or unacceptable, or both. An imperialist, he was an ardent supporter of the British Empire. He was most likely a racist, a failing rampant at the time. He was the author of the expression “the white man’s burden,” the title of a poem in which Kipling urged the United States in 1899 to take over the Philippines in order to bring civilization to “Your newly caught sullen peoples, Half devil, half child.” On the other hand, he could admire other peoples. In his Ballad of East and West he wrote: “…there is neither East nor West, Border, nor Breed, nor Birth, When two strong men stand face to face, tho’ they come from the ends of the earth!” Just six years after his death, George Orwell called Kipling “a jingo imperialist” who was “morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting.” Today, a veritable cottage industry has developed parsing the racism explicit and implicit in The Jungle Book. There is also an ongoing debate over the degree to which Kipling was sexist. He was author of the expression “the female of the species is more deadly than the male.”

Kipling was born in Bombay in British India in 1865. His father, Lockwood Kipling was professor of architectural sculpture at the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeboy School of Art. His mother was Alice McDonald. Home was a house on the school grounds. “Kipling House” still stands on the campus grounds of Sir J.J. School of Art, now affiliated with the University of Mumbai. As a young child, Kipling was sent to England to live with a foster family. He was terribly unhappy there. Taken out of the home, he later attended the United Services College at Westwood Ho!, a quirkily named village in Devon. As a teenager, he returned to India, where he worked as a journalist in Lahore. It was here that he began to write stories about soldiers’ lives in British India, and attracted attention as an author. He returned to England in 1889, via the Pacific and North America, with several stops in Canada, including Victoria, Vancouver, Calgary, Medicine Hat and Toronto. Three years later, he returned to Canada with his new wife Carrie (née Balestier) after a honeymoon trip to Japan. Kipling purchased property in Vancouver, attracted by its harbour, its laid-back lifestyle and its economic prospects. Kipling also found the city to be comfortably familiar. The British flag flew over its buildings, and, in his estimation, the locals spoke proper English. However, they never lived there. Instead, the Kiplings settled down for several years in Vermont in the community where his American-born wife was raised. It was in Vermont that Kipling wrote The Jungle Book stories.

Rudyard Kipling and family returned to England for good in 1896 owing to discord with his brother-in-law who was also Kipling’s neighbour, and political tensions between the United States and Britain over British Guiana. After living for a time on the southwestern coast of England in Dorset, they bought an old manor house in Sussex in 1902.

Kipling was an inveterate traveller, with multiple voyages throughout Asia, Australia, South Africa, Europe, and North America. He had a great affection for Canada which he viewed as the eldest sister of Mother England’s Dominions that could one day provide leadership to the Empire. He described Canada as a country that has “a hard, tough, bracing climate that puts iron and grit into men’s bones, and that if things don’t move so fast as in the States they are safer.” However, he apparently also thought that Canada was “constipating,” and that when he spoke to Canadians, he needed to speak in short sentences since Canadians couldn’t “carry anything more than three and a half lines in their busy heads.” In turn, many Canadians resented his characterization of Canada as “Our Lady of Snows” as it might put off potential immigrants.

In the autumn of 1907, Kipling, now at the height of his popularity, made a cross-country tour of Canada, in part to see how the west had changed, especially Calgary and Medicine Hat, since his visit eighteen years earlier. He made the trip in luxury, on a private train carriage provided to him by Sir William Horne, the President of the Canadian Pacific Railway. In cities along his route, he stopped to visit the sights. He was invariably invited to speak. He later commented that in Canada “there is a crafty network of business men called Canadian Clubs. They catch people who look interesting, assemble their members during the mid-day lunch hour, and, tying their victim to a steak, bid him discourse on anything that he thinks he knows.”

Advertisement for Kipling's book, Letters to the Family, on his reflections about Canada

Advertisement for Kipling's book, Letters to the Family, on his reflections about Canada

The Ottawa Journal, 9 May 1908He briefly passed through Ottawa at the end of September on his way west before returning to the capital for a weekend stay on Saturday, 19 October as the guest of Lord and Lady Grey at Rideau Hall. The Governor General’s Secretary, Colonel (later Major-General Sir) John Hanbury-Williams, was an old friend of Kipling. He was greeted at the train station early in the morning by the Governor General’s staff. That afternoon, Kipling met the press at Rideau Hall. The interview was a love-in. One journalist reported that Kipling was “in every way interesting and interested,” and was a “fresh and vigorous personality.” Kipling focused his remarks on immigration and trade, the hot topics of the time—not so different from today! These were subjects to which he returned in his Monday’s address to the Ottawa Canadian Club after taking the Sunday off to relax with Lord and Lady Grey and their friends. Also on that Saturday afternoon, Kipling met with representatives of the South African Veterans’ Association.

Kipling’s Monday luncheon speech to the Canadian Club was held in the railway committee room of the House of Commons owing to the large number of people eager to hear the Poet of the Empire speak. More than three hundred men were in attendance, including Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier. At the lunch, Laurier commented that not all Canadians took offence at Kipling’s characterization of Canada as “our Lady of Snows.” Laurier opined, that “the Canadian winter is one of the best of the blessings with which nature has dowered the Dominion.”

In his speech, Kipling despaired of Britain: “Sometimes one can only look out the window and pray, and say nothing.” His fears reflected the Mother Country’s blasé attitude towards its overseas dominions, including its unwillingness to support imperial trade preference as a means of helping to cement the Empire together. Britain had pursued a free trading policy since the mid nineteenth century. Consequently, it treated all trading partners alike regardless of whether they were part of the Empire or not. In contrast, Kipling praised Canada, which maintained tariffs to protect its industries, for instituting an imperial preference for British and subsequently Empire-made goods that had led to steamships trading regularly between New Zealand and South Africa and Canada. In parenthesis, a few years later Kipling waded into the 1911 Canadian political debate on the merits of reciprocity [a.k.a. free trade] with the United States, sending a letter that was widely printed in Canadian newspapers that Canada risked “its soul” should reciprocity be introduced. “Once that soul is pawned for any consideration Canada must inevitably conform to the commercial, legal, financial, social, and ethical standards which will be imposed upon her by the sheer admitted weight of the United States.” The reciprocity supporting Liberal Party lost the general election. Decades later, the very same sentiments were expressed during the 1980s when the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement was being negotiated by the Conservative government of Brian Mulroney.

Immigration was the other hot topic that Kipling addressed. In British Columbia, there had been an influx of migrants from China, Japan and India that had led to an anti-immigrant riot. The Oriental Exclusion League based in British Columbia circulated a petition urging the Canadian government to prohibit all “Oriental immigration.” The petition said that British Columbia “has been in the past, and will continue to be, the dumping ground of Oriental laborers, notably Hindoos, Japanese and Chinese; that at present there are 30,000 Orientals of the foregoing races in British Columbia; that the Orientals enter into competition with white men, whom they have largely displaced in fishing and lumbering industries and have usurped the places amongst unskilled laborers that would otherwise be filled by white men; that the Orientals are not capable of assimilation with the white races of Canada…” The Oriental Exclusion League threatened “measures to prevent the debarkation of Orientals in Vancouver” if its demands were not met. The League was not some crank organization expressing racist views. Robert Borden (later Sir), leader of the opposition Conservative Party, said in Vancouver that British Columbia “must remain a British and Canadian province, inhabited and dominated by men in whose veins runs the blood of those great pioneering races which built up and developed not only Western, but Eastern Canada.”

Rudyard Kipling by Elliot & Fry, circa 1935Kipling responded to these events by saying British Columbia’s underlying problem was a shortage of labour rather than too much Asian immigration. And, “…if you won’t have yellow labor, you must have white.” He argued that Canada should fill up with white immigrants from Britain, with government assistance if necessary, so that “you will not notice the Orientals.” He added that “If you wait for your country to be settled with your own stock or carefully chosen immigrants it would be all right, but it is only a question of time until the ring breaks in the old lands and the flood seeps to Canada. There are many hungry people wandering around the world, and Canada must prepare to receive them.”

Rudyard Kipling by Elliot & Fry, circa 1935Kipling responded to these events by saying British Columbia’s underlying problem was a shortage of labour rather than too much Asian immigration. And, “…if you won’t have yellow labor, you must have white.” He argued that Canada should fill up with white immigrants from Britain, with government assistance if necessary, so that “you will not notice the Orientals.” He added that “If you wait for your country to be settled with your own stock or carefully chosen immigrants it would be all right, but it is only a question of time until the ring breaks in the old lands and the flood seeps to Canada. There are many hungry people wandering around the world, and Canada must prepare to receive them.”

Kipling left Ottawa following his Canadian Club speech for Montreal where he was given an honorary degree by McGill University. The next year he published Letters to the Family about his trip across Canada. In it he expressed a number of fascinating opinions about Canada and Ottawa. On Canada’s bilingual nature, he thought that “There are strong objections to any non-fusible, bi-lingual community within a nation.” However, French Canada’s “unconcerned cathedrals, schools and convents,” and “the spirit that breathes from them, make for good.” English and French together make “a good blend in a new land.” He was also impressed with Canadian cities’ “austere Northern dignity.” He thought that “Montreal, of the black-frocked priests and the French notices had it” as did “Ottawa, of the grey stone palaces and the St. Petersburg-like shining water frontages” and Toronto that was “consummately commercial.”

Rudyard Kipling died in January 1936 at the age of 71.

Sources:

Experimental Wifery, 2017. “The Female of the Species Is More Deadly Than The Male,”.

History of Metropolitan Vancouver (The), 2017. Rudyard Kipling in Vancouver,.

Kipling, Rudyard, 1908. Letters to the Family, Macmillan Company of Canada: Toronto.

———————, 1930s. “Sound recording of Kipling speaking on Canadian writers and poets,”.

Kipling Society (The), 2017, http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/index.htm.

Lycett, Andrew, 1999. Rudyard Kipling, Weidenfeld & Nicolson: London.

Orwell, George, 1942. Rudyard Kipling, http://orwell.ru/library/reviews/kipling/english/e_rkip.

Ottawa Citizen (The), 1907. “Mr. Borden And Asiatic Immigration,” 1 October.

————————-, 1907. “Kipling Arrives,” 19 October.

————————-, 1907. “Famous Author Is In Ottawa,” 19 October.

Ottawa Journal (The), 1899. “Personal And Pertinent,” 25 April.

————————–, 1907. “Petitioning The Premier,” 30 September.

————————–, 1907. “Kipling Off To The West,” 1 October.

————————-, 1907. “Kipling Will Be Here Saturday,” 17 October.

————————-, 1907. “Unrestricted Immigration,” 17 October.

————————-, 1907. “Rudyard Kipling; the Man and his Work,” 17 October.

————————-, 1907. “Kipling Will Speak Monday,” 18 October.

————————-, 1907. “Fill Canada With Whites, Asiatics Will Disappear,” 21 October.

————————-, 1907. “Great Reception To Mr. Kipling,” 21 October.

————————-, 1907. “Mr. Kipling and Veteran Officers,” 21 October.

————————-, 1907. “Kipling’s Message,” 21 October.

————————-, 1936. “Nation’s Bard, Kipling, Loses Gallant Fight Against Death,” 18 January.

Price, John, 2007. “Orienting the Empire: Mackenzie King and the Aftermath of the 1907 Race Riots,” BC Studies, no. 156, Winter 2007/08.

Ricketts, Harry, 1999. Rudyard Kipling, A Life,” Carroll & Graf Publishers, Inc.: New York.

Sikov, Ed, 2016. “Are ‘The Jungle Books’ Racist or Not? And Why You Should Read Them Either Way,” Lit Reactor.

Trendacosta, Katharine, 2016. “Reminder: Rudyard Kipling Was a Racist Fuck and the Jungle Book is Imperialist Garbage,” io9.Gizmondo.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Some Chicken! Some Neck!

29 December 1941

News that Japan had attacked and destroyed much of the U.S. Pacific Fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor in early December 1941 simultaneously appalled and elated British Prime Minister Winston Churchill. While disheartened by the destruction and loss of life, he was overjoyed that the sleeping American giant was finally fully awake to the global threat posed by the Axis Powers. With the English-speaking peoples of the world now united against the common foe, Churchill was convinced that eventual victory was assured.

Churchill immediately made plans to go to the United States to confer with his new war ally, President Franklin Roosevelt. Initially, Roosevelt advised Churchill against the trip, citing the enormous risks of crossing the U-boat infested, North Atlantic, as well as domestic American political reasons; he was unsure of Churchill’s reception. But there was no dissuading the redoubtable British Prime Minister. Accompanied by staff and senior military leaders, he arrived on American soil on 22 December, just two weeks after the Pearl Harbor attack, having journeyed to North America on the newly-commissioned battleship HMS Duke of York. The perilous journey took ten days. Churchill spent much of the next four weeks a guest of the Roosevelts’ at the White House. In so doing, a close, personal bond was established between the two leaders. After spending Christmas Day with the Roosevelt family, Churchill addressed the joint Houses of Congress on Boxing Day. At the Senate rostrum, Churchill reminded his audience, and the American people who were listening to his speech by radio, that he was half American himself, and, but for a quirk of fate, he might have had a seat there instead of the House of Commons in London. He also warned his audience not to understate the severity of the ordeal they faced. He predicted dark days to come in 1942, but was confident in their ultimate success. Churchill’s frankness, and boundless enthusiasm, charmed U.S. lawmakers, who gave him a thunderous ovation.

While the prime reason for his trip to North America was to woo the United States, and to coordinate the next steps in the Allied military campaign, Churchill made a two-day side journey to Canada. With the American trip off to an excellent start, Churchill felt that he was able to accept an invitation from Canada’s Governor General, the Earl of Athlone, and Prime Minister Mackenzie King to visit Ottawa. The trip was a “thank-you” to the Dominion for the significant contribution the country had made to the war effort in the form of manpower, materials, food, and money.

For obvious security reasons, Churchill’s visit to Canada was kept top secret until only shortly before his arrival in Ottawa. But when the news broke, a wave of excitement gripped the nation’s capital. Flags and bunting quickly appeared on the city’s buildings and telephone poles. At shortly after 10am on Monday, 29 December, Winston Churchill arrived at Ottawa’s Union Station on President Roosevelt’s luxurious, bullet-proof, personal train, complete with the President’s personal valet, chef, and body guards. Also on board was Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King, who had travelled down to Washington on Christmas Day to confer with American and British officials, and to witness first hand Churchill’s historic address to the U.S. Congress.

Despite the cold and a light snow falling, twenty thousand people filled the streets around Ottawa’s Union Station to catch a glimpse of Churchill. The official welcoming committee consisted of representatives of the Governor General, Cabinet Ministers, Senators, Members of Parliament, heads of diplomatic corps resident in Ottawa, and Mayor Stanley Lewis. As the train backed into the station, the British Prime Minister stood at the end-car platform, wearing a dark overcoat and a dark blue muffler, with a heavy walking stick in hand, and his characteristic cigar clenched between his teeth. He greeted the crowd’s welcoming cheers with broad smiles, waves of his hat, and his famous “V” for Victory sign. On exiting the train, Churchill was swamped by enthusiastic citizens who had burst through the police cordon as he made his way to the official car. Apparently, he was forced to use his elbows to reach the car, though he took all the jostling in good humour.

Churchill was driven from Union Station to Rideau Hall, the residence of the Governor General, with whom Churchill would be staying on his short visit to Ottawa. Along the processional route, which took his motorcade down Nicholas Street, the Laurier Avenue Bridge, Mackenzie Avenue, Lady Jane Drive, and Sussex Avenue, thousands of Ottawa citizens cheered themselves hoarse. People clambered on top of cars to get a good view of their wartime hero who had sustained an Empire through more than two desperate years of war. Office windows on the route were jammed with spectators. Security was provided by scores of RCMP and Ottawa police both in uniform and in plain clothes.

Newspaper accounts commented that Churchill had been accompanied to Ottawa by Sir Charles Wilson, the prime minister’s personal physician. The Ottawa Citizen pointed out that Wilson’s presence signified nothing; it was “not that Mr. Churchill is in the least need of medical attention.” On the contrary, the paper said that the 66-year old British Prime Minister was “fighting fit,” looked younger than expected, and there was “no evidence of fatigue, nothing to indicate that the weight of his responsibilities is proving too much for him.” In reality, that assessment was far from the truth. Years later, it was revealed the night after his triumphant Congressional speech, just two days before leaving for Ottawa, Churchill experienced a gripping pressure in his chest, with pain radiating down his left arm. Wilson recognized the symptoms of a heart attack, but said nothing, telling Churchill that he had simply overdone things. Fortunately, for Churchill and the entire world, the symptoms eased, and the British Prime Minister continued with his gruelling schedule without further incident.

The following afternoon, Churchill was taken in procession to Parliament Hill to address a joint session of the Senate and House of Commons. As Parliament was officially in recess, members were recalled for Churchill’s speech. Before entering the Centre Block, Churchill inspected a guard of honour consisting of personnel from the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteers, RCAF, and cadets from the Canadian Officers’ Training Centre in Brockville. In charge of the guard was Major Alexandre Dugas of the Maisoneuve Regiment, recently returned from Britain. Again, the British leader was given a huge welcome by the many thousands of Ottawa citizens. To their cheers, Churchill got out of his car, and raised his hat in acknowledgement.

Inside, the House of Commons was packed. Almost 2,000 people, including MPs, Senators, privy councillors, provincial premiers, judges, clergy, high-ranking military leaders, and heads of Commonwealth and foreign delegations, sat on the parliamentary benches and on temporary seats set up on the Commons’ floor. The galleries too were packed with humanity, including a virtual army of photographers and movie cameramen there to record the historic proceedings.

At 3pm, Churchill took his seat to the right of the Commons Speaker, the Hon. James A. Glenn; the Senate Speaker, the Hon. Georges Parent, sat on Glenn’s left. Churchill’s arrival was the signal for minutes of near-frantic cheering from the assembled multitude. After the words of welcome, Churchill rose and strode over to the end of the table nearest the Speaker’s chair, where a bank of microphones had been set up. When silence was restored, Churchill addressed the throng, his words transmitted live over CBC radio, and to the crowds outside on Parliament Hill over a loudspeaker system. In his speech, one of his most memorable, Churchill thanked the Canadian people for all they have done in the “common cause.” He also said the allies were dedicated to “the total and final extirpation of the Hitler tyranny, the Japanese frenzy, and the Mussolini flop.” Alluding to defeatist comments made by French generals who in 1940 had said that in three weeks England would have her neck rung like a chicken, Churchill famously said “Some Chicken! Some Neck!” Simple words, but ones that captured the resolve of a people to fight on to victory. The House erupted into cheers.

After his speech, Churchill retired to the Speaker’s chambers. There, Yousef Karsh, the photographer, persuaded the British leader to pose for an official portrait. Churchill gruffly agreed, giving him five minutes. When Karsh took Churchill’s iconic cigar out of his mouth, Churchill glowered. Karsh immediately snapped a picture, capturing the pugnacious pose that became symbolic of British resistance to Nazi aggression. (See Karsh photograph.) Karsh later said “By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent, he could have devoured me.” The photograph made Karsh internationally famous. Mackenzie King was so delighted with the photograph that he sent three copies to Churchill.

The next day, Churchill returned to the United States for more talks with President Roosevelt and U.S. political and military officials, as well as for a short, but much needed, holiday in Florida. On 16 January 1942, Churchill finally left America on a Boeing 314 Flying Boat called the Berwick, departing from Virginia to Bermuda. The intrepid leader took the controls of the plane and flew it for part of the journey. Arriving in Bermuda, he had been scheduled to rendez-vous with the battleship Duke of York for the remainder of the trip back to the United Kingdom. However, advised that the weather was favourable, and eager to get back home after being away for more than a month, he continued his journey to Britain by plane—an audacious undertaking; transatlantic air travel was still in its infancy. While the flight itself was largely uneventful, disaster was narrowly averted when the airplane accidently flew within five minutes of the coast of occupied France. When a course correction was finally made, the flying boat, now headed north to Plymouth Harbour, was identified by British coastal defences as a German bomber. Six Hurricane fighters were sent to intercept the airplane and shoot it down. Thankfully, they were unable to locate it. As Churchill laconically put it “They failed in their mission.”

Churchill returned to Canada in late 1943 to confer once again with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Mackenzie King. By then, the tide of war had finally turned. Instead of focusing on how best to resist the Axis onslaught, the leaders, at La Citadelle in Quebec City, plotted the invasion of Nazi-occupied France.

Sources:

British Pathé, 1941. “Churchill in Ottawa".

CBC Digital Archives, 2015. 1941: Winston Churchill’s ‘Chicken’ Speech.

Cobb, Chris, 2011. Winston Churchill 70 Years Ago: “Some Chicken! Some Neck!” The Churchill Centre.

Dr. Tsai’s Blog, 2011. Did Churchill have a heart attack in December 1941?”.

Evening Citizen (The), 1941. “Grim War Ahead, Churchill Warns U.S.,” 26 December.

————————–, 1941. “Prime Minister Churchill To Visit Ottawa And Address Parliament, 27 December.

————————–, 1941. “City Prepares Warm Welcome For Churchill,” 27 December.

————————–, 1941. “Crowd To Hear Speech On Parliament Hill Tomorrow,” 27 December.

————————–, 1941. “Mr. King Returns After Taking Part In War Conference,” 27 December.

————————–, 1941. “Churchill Takes Ottawa By Storm As Crowds Shout Tumultuous Welcome,” 29 December.

————————–, 1941. “Churchill Again Widely Cheered On Hill Arrival,” 30 December.

————————–, 1941. “Churchill Promises To Carry The War Right To Homelands of Axis,” 31 December.

Karsh.org, 2015. “Winston Churchill, 1941,”.

Sir Winston Churchill Society of Ottawa, 2015.

Wilson, James Mikel, 2015. “Churchill and Roosevelt: The Big Sleepover at the White House, Christmas 1941 – New Year 1942,” Columbus, Ohio: Gatekeeper Press.

Maier, Thomas, 2014. “A Wartime White House Christmas With Churchill,” The Wall Street Journal, 21 December.

World War II Today, 2012. “January 16, 1942: Churchill Returns to Britain By Air,”.

Image:

Winston Churchill in the House of Commons, Ottawa, 30 December 1941, Library and Archives Canada, C-022140.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

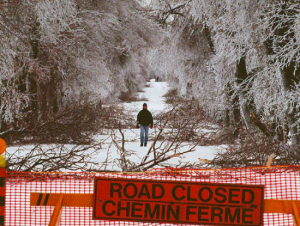

Winter's Icy Grip

5 January 1998

Ottawa’s citizens claim that their city is the second-coldest capital city after Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. While this may or may not be accurate, it’s undeniably true that you better pack your woollies if you are planning a winter visit. During the month of January, the city experiences frigid temperatures of below -9°C more than half the time, with the thermometer occasionally dipping to -30°C, or lower.

Despite Ottawa’s frosty reputation, the winter of 1997-98 began significantly milder than usual, with the city’s temperatures moderated by the impact of el Niño, a warm current that arrives around Christmas off the Pacific coast of Latin America. Usually, the current is relatively weak and is of little meteorological consequence. However, every several years, the current is warmer than usual and can have a major effect on atmospheric conditions across North America. In the fall of 1997, el Niño arrived much earlier and was far warmer than usual. The water temperature in the eastern Pacific rose by more than 4 degrees Celsius, the most in more than 50 years. In December 1997, Ottawa’s average temperature was several degrees above normal leading to complaints from winter enthusiasts about the lack of snow.

With mild weather persisting, a powerful low pressure system stalled in early January 1998 across the Great Lakes, its eastward path blocked by a large high pressure system over Labrador as well as an unusually strong Bermuda-Azores high over the North Atlantic. As the Labrador high pressure swept cold Arctic air southward into Ontario and Quebec, the low pressure system pumped warm moist air from the Gulf of Mexico northward. Slipping below the warm Gulf air, the heavier Arctic air began to collect in the Ottawa and St. Lawrence River valleys. The conditions were ripe for a significant accumulation of freezing rain.

Freezing rain is precipitation that falls when the temperature is below 0°C in the form of super-cooled rain rather than as snow or ice pellets. The water droplets freeze on contact, coating all exposed surfaces with a layer of ice. This phenomenon occurs when a thin layer of cold air is trapped beneath a thick layer of warm air. Moisture, which at high altitudes may start to fall as snow, melts when it passes through the warm air zone. The resulting water drops have insufficient time to re-freeze into ice pellets when they pass through the thin layer of cold air immediately before hitting the earth. Located in a valley, Ottawa and its neighbouring communities are frequently hit by freezing rain, experiencing at least a dozen episodes in an average year. But what they were about to experience in January 1998 was anything but average.

At 3.00am on the morning of 5 January, freezing rain began to fall in Ottawa. With temperatures hovering close to the freezing point, it didn’t stop, other than for an occasional pause, until 4.00pm four days later. The storm was massive. At its height, freezing rain was falling from southern Ontario, through to Kingston, Ottawa, Montreal, the eastern townships of Quebec, parts of New Brunswick and Nova Scotia, upstate New York and New England. In total, Ottawa received 85 millimetres of precipitation over that period, most of it in the form of freezing rain. Montreal and Cornwall, located in the St. Lawrence River Valley, fared even worse, each getting more than 100 millimetres of precipitation.

Quickly, all exposed surfaces— every road, sidewalk, building, branch and power line—became layered with a thick coating of ice exceeding three centimetres thick. Roads became impassable. Branches littered the ground. Trees, bent double under as much as two tonnes of ice, snapped with a sound like cannon fire. Many of the Arboretum’s rare specimen trees were destroyed. Behind the Nepean Sports Centre, the recreational pathways used in winter for cross-country skiing were blocked with downed trees and branches. Often only splintered trucks were left standing, reminiscent of images of World War I.

Falling branches and the weight of the ice brought down tens of thousands of kilometres of power lines and thousands utility poles. High-tension transmission pylons that fed power to Ottawa, Montreal and other major cities were felled, leaving more than 4 million hydro customers without electricity for days, some for weeks. At night, the sound and flashes of transformers shorting out provided an eerie accompaniment to the tinkling of freezing rain and the crash of falling branches.

Regional Chair Bob Chiarelli declared a state of emergency throughout the region. Rural communities, such as Rideau, Osgoode, and Goulbourn, were particularly hard hit. There, the lack of electricity meant water pumps could not operate. Barns collapsed and livestock perished. Across the Ottawa River, emergencies were declared throughout west Quebec. Thousands of government workers were told to stay home. Universities and colleges closed. In an unprecedented move, Bayshore, St. Laurent and the Place D’Orléans shopping centres were also closed and transformed into emergency shelters.

The army was called out to assist emergency workers to clear debris and to deliver supplies to shelters. Called Operation Recuperation, 2,000 soldiers from Petawawa and Borden helped in the Ottawa area, with their headquarters set up in the Cartier St Drill Hall. Many thousands more helped through the rest of Ontario and Quebec. In total, more than 15,000 troops were mobilized.

By 14 January, the city, and the region more generally, was getting back to normal. Power had been restored to most urban areas through the truly heroic efforts of hydro linesmen, many brought in from neighbouring provinces and U.S. states. Rural communities continued to suffer, however; some unfortunate residents remained without power for more than a month through the worst of a Canadian winter. It is believed that 28 deaths were caused directly by the storm, most from hypothermia. Roughly 600,000 people had to leave their homes. More than 30,000 utility poles and 130 major transmission towers collapsed. Millions of trees were destroyed, with an estimated 100,000 downed in the Ottawa area alone. The damage done to maple trees severely affected maple syrup production for years to come. The storm was Canada’s largest natural disaster with estimated losses of roughly $5 ½ billion.

Sources:

National Weather Service, Forecast Office, Burlington Vt, 2008. 10th Anniversary of the Devastating Ice Storm in the Northeast:.

Susan Monroe, 2013. Canadian Ice Storm in 1998, Ask Canada.com.

The Ottawa Citizen, 2008. “The Great Ice Storm of ’98,”.

The Weather Network, 2009. “Taken By Storm—1998 Ice Storm”.

Wikipedia: North American Ice Storm of 1998.

Environment Canada, 2013. Canada’s Ten Top Weather Stories of 1998.

Weather Spark, Average Weather for Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Image: Experimental Farm, Ash Lane, 1998, David Chan, The Ottawa Citizen.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.

Heartbreak Hotel

3 April 1957

In 1956 came a musical phenomenon the likes of which the world had never before seen. Elvis Aaron Presley, a poor, twenty-one year old boy from Nashville Tennessee with a ducktail haircut, smoldering good looks and deep blue eyes, took the world by storm. His seductive, wide-ranging voice, and tunes that combined black rhythm and blues with country music, electrified the youth of America, starved for a fresh sound. “Heartbreak Hotel,” released by RCA Victor in January 1956 and Elvis Presley’s eponymous debut LP released two months later were instant successes. Both rocketed to the top of Billboard charts, and stayed there for weeks. On stage, Presley’s singing prowess and sexually-charged performances wowed teenagers, and shocked a deeply conservative American establishment.

After his first album was released, Presley’s career, astutely managed and promoted by Colonel Tom Parker, went into overdrive with multiple appearances by the young singer on U.S. nationwide television, including the CBS Stage Show, the Milton Berle Show, and the Steve Allen Show. An estimated 60 million viewers watched Presley perform on the iconic Ed Sullivan Show in early September 1956. At this appearance, Presley sang the title song of his up-coming movie Love Me Tender for the first time in public. Advance sales of the song went gold before the movie’s release by 20th Century Fox that November. Owing to the wild success of his first appearance on his show, Sullivan invited Presley back twice more over the next four months. Many of his viewers were in Canada, able to pick up the American television signals.

Now a celebrity, Presley went on a multi-city eastern tour in March 1957 which brought him and his backup group, the Jordanaires, to Fort Wayne, St Louis, Philadelphia, Buffalo, and, across the border for the first time, to Toronto and Ottawa. Other than a stop in Vancouver later that year, it was the only time Presley was to perform outside of the United States. After back-to-back shows at Maple Leaf Gardens wearing his famous Nudie Cohen-design gold lamé suit in front of 30,000 adoring fans, Presley and his entourage boarded the overnight train to Ottawa. They arrived in the nation’s capital at 8am on 3 April 1957.

The Ottawa Journal disparagingly reported that Presley skipped lightly like a girl through Ottawa’s downtown Union Station, passing bemused and largely unmoved commuters on his way to an awaiting taxi. The singer was described as “red-eyed and rumpled with sleep,” with “traces of makeup and what looked like mascara” failing “to hide tired lines around the wobble-singer’s Grecian nose.” Presley, who looked like “any Canadian boy who needs a haircut,” was wearing a dark suit, and a velvet shirt, covered by a “crumpled rosy beige raincoat, with smudgy white buckskin shoes.” Protected by “a flying wedge” of police guards and his entourage, he was taken by taxi to an undisclosed location for some much needed sleep, safe from the prying eyes of teen-aged fans who were laying siege to the city’s hotels in hopes of catching a glimpse of the young singer.

Later that day, Presley played two sold-out gigs at the old Ottawa Auditorium, located on the corner of O’Connor and Argyle Streets where the YMCA is today. Ticket prices ranged from $2 to $3 for the 5pm show, and $2.50 to $3.50 (roughly $20 to $30 today) for the 8.30pm performance. While Presley was the headline performer, also on the program were Frankie Trent, a tap dancer, and Frankie Connors, an Irish tenor. Needless to say, the warm-up acts were at best tolerated by fans who were there to see Elvis in the flesh. Many had come from afar to be part of the fun. Busloads of teenagers made their way from Cornwall, Ontario, and from upstate New York. A special 10-car special CPR train called the “Presley Special,” or the “Rock N’ Roll Cannon Ball,” brought hundreds of fans from Montreal who paid $11 for the round-trip, which included the price of admission. Some of the riders were the lucky winners of a Montreal, city-wide contest which asked them to answer the question “Why I would like to go to Ottawa April 3.” En route, four rock and roll guitarists got the fans into the mood.

16,000 mostly teenaged fans saw Elvis at the Auditorium, though a number of adults sporting “I love Elvis” buttons were spotted in the crowd. The singer again wore his trademark gold lamé jacket and gold accessories, but this time chose to wear dark trousers. Keeping to the adage of always leaving them wanting more, his sets were only 40 minutes long, consisting of nine songs. But he played most of his big hits of the day, including Don’t be Cruel, You Ain’t Nothin But a Hound Dog and Heartbreak Hotel. He also sang Love Me Tender, his adaptation of an old U.S. Civil War love ballad Aura Lee (or Aura Lea). Now considered a classic, ranked by Rolling Stone magazine as one in the greatest 500 songs of all time, the Ottawa Journal reporter called Presley’s rendition “a travesty.” It was reported that the gate for the two performances amounted to $45,000, of which Elvis’s cut was $20,000.

Elvis’s trip to Ottawa was not without controversy. As was often the case south of the border, many adults considered Presley’s on-stage gyrations immoral and un-Christian. Across the city, students were warned to behave themselves, and to do nothing that would bring disrepute on themselves or their schools. The nuns at Notre Dame Convent went further, pressuring their students to promise that they would not take part in the Elvis festivities. They kids were obliged to copy from the blackboard and sign a letter that read “I promise that I shall not take part in the reception accorded Elvis Presley and I shall not be present at the program presented by him at the Auditorium on Wednesday April 3 1957.” Some went notwithstanding the pledge. Those caught were suspended by the school, though they were later reinstated following complaints from their parents.

Fearing that crowds of screaming, near hysterical, teenagers might become disorderly as they had been at previous Elvis performances, a hundred special police and guards were on hand to keep control and to stop spectators rushing the stage. But the guards had relatively little to do besides keeping the aisles clear. Although the throngs of fans proved to be well behaved, they were extremely loud. So loud were they that it was difficult for anybody except those at the very front rows in the arena to hear Presley sing. Poor audio facilities at the Auditorium didn’t help either. But most spectators didn’t appear to mind, content to watch Presley do his thing on stage and be part of the event. As reported by the Journal “With every shimmy the idol’s knees further beckoned the floor. The closer they came, the louder became the screams and when he finally rested on the stage floor—thunder!”

Between performances, a quieter, more subdued Elvis Presley was on display. He greeted a number of young female fans that had been chosen to come backstage, and was photographed with them. Young Janet Fulton, only 13-years old at the time and, fortunately for her, a student at the Sacred Heart Catholic School rather than at the Notre Dame Convent, not only met her idol but received a kiss on the cheek. Presley also gave an interview to Gord Atkinson, host of the CFRA radio’s popular weekly program Campus Corner. Presley politely answered Atkinson’s questions about his sudden popularity, his purchase of Graceland mansion the previous week, his music, and family life. Atkinson then presented him with a scroll indicating that he had been chosen the “Top Artist” by the listeners of Campus Corner. Presley courteously thank him, and replied that he had received more fan mail from Toronto, Ottawa and Montreal than anywhere else.

Pictures were also taken of Elvis Presley with Ottawa jazz musician, drummer Arni May. As union rules required local talent to be hired for the performance, Presley requested that the Ottawa drummer, then only 18-years old, and his orchestra, play with him and the Jordanaires. May recalled that Elvis was a “first-class gentleman,” and had treated him like a friend. May was paid $30 as the band leader; his band members each received $20. May reprised his performance in August 2007 at an Elvis tribute concert at the Pacific National Exposition, fifty years after the singer’s only western Canadian event.

At the end of the evening performance, Elvis left the stage and quickly left the Auditorium never again to return to Ottawa. But behind him, he left memories of a lifetime for thousands of Ottawa teenagers.

Sources:

Beagley, Piers, 2011. “Kissed by Elvis”—Interview with Janet Fulton, Elvis Information Network.

CBC, 2014. Elvis shakes his pelvis in Canada, CBC Digital Archives, CBC News Roundup, 2 April 1957.

City of Ottawa, Elvis Presley.

Click It Ticket, 2014-2018. All About the King, https://www.clickitticket.com/elvis/about-the-king/biography.asp.

Elvis Australia, 2014. Elvis Presley: Ottawa, Canada, 3 April 1957.

Elvis Presley, Official Website of the King of Rock and Roll, 2014. Elvis Presley Biography.

Plummer, Kevin, 2013. “Historicist—Elvis in Toronto, 1957,” Torontoist.

The Ottawa Citizen, 1957. “Flying Wedge Gets Elvis Safely Past Giddy Girls,” 3 April.

———————–, 1957. “Riding the Elvis Special was Weird and Wonderful,” 4 April.

The Ottawa Journal, 1957. “Presley in Ottawa, Skips Through Union Station,” 3 April.

————————, 1957. “16,000 See Elvis in Ottawa Shows,” 3 April.

————————, 1957. “Teenagers Beseige (sic) Hotels,” 3 April.

————————, 1957. “Asked Girls Stay Away From Elvis,” 3 April.

————————, 1957. “Overwhelmed by Police Control,”

Toronto Sun, 2012. “Ottawa’s Arni May played with Elvis,” 9 January.

Vancouver Courier, 2007. “Arni’s ready to beat drums again for the King,” 3 August.

Images: A. Andrews, C. Buckman, D. Gall, T. Grant, 3 April 1957, City of Ottawa Archives.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.