Museum Club Visit to Manotick

Under threatening skies, the Museum Club visited Dickinson Square in Manotick on Sunday, August 18, 2024, for a guided tour of Watson’s Mill and Dickinson House. Eighteen of the twenty registered participants took the chance and were rewarded with a wonderful experience.

After we gathered and were welcomed by our host Avery Geboers, we split into two groups, one starting in Watson’s Mill and the other in Dickinson House.

Inside Watson's MillWatson’s Mill was built by Moss Kent Dickinson and Joseph Merrill Currier, one of four mills to be constructed in the general location, including a sawmill (1859), a flour & grist mill (1860, Watson’s Mill), a wool carding mill (1861), and a bung, plug and spile mill (1875, 1888). The 4-storey mill was a marvel of automation for its day, powered by water turbines, rather than a waterwheel, which allowed the mill to operate year round. An ingenious combination of belts and chutes enabled the mill to be run by one person. As far as we know, we were not joined on our tour by the ghost of Ann Crosby Currier, (wife of Joseph for only 6 weeks), who died in a tragic accident in the mill in 1861 and is said to have never left.

Inside Watson's MillWatson’s Mill was built by Moss Kent Dickinson and Joseph Merrill Currier, one of four mills to be constructed in the general location, including a sawmill (1859), a flour & grist mill (1860, Watson’s Mill), a wool carding mill (1861), and a bung, plug and spile mill (1875, 1888). The 4-storey mill was a marvel of automation for its day, powered by water turbines, rather than a waterwheel, which allowed the mill to operate year round. An ingenious combination of belts and chutes enabled the mill to be run by one person. As far as we know, we were not joined on our tour by the ghost of Ann Crosby Currier, (wife of Joseph for only 6 weeks), who died in a tragic accident in the mill in 1861 and is said to have never left.

Inside Dickinson HouseDickinson House, across the street from the mill was built in 1867 and served as the village post office, general store and home to the Dickinson family and all subsequent mill owners. The house is furnished in pieces from the late 1800s, though only one chair and a notary seal are from the Dickinson family.

Inside Dickinson HouseDickinson House, across the street from the mill was built in 1867 and served as the village post office, general store and home to the Dickinson family and all subsequent mill owners. The house is furnished in pieces from the late 1800s, though only one chair and a notary seal are from the Dickinson family.

The costumed interpreters in both the mill and the house were poised, polite, professional and extremely knowledgeable. They added greatly to our understanding of the site and our overall enjoyment of our visit.

When both tours were completed, we gathered again in the mill. On most summer Sunday afternoons there is a milling demonstration, but due to unfortunate circumstances, this could not be done on the day of our visit (a good reason for another trip). Our hosts did, however, arrange for us to start the water turbine so we could see some of the mill equipment in motion. The President of the Historical Society of Ottawa, Emma Kent, was put to work, turning the heavy wheel to start the mill. You can watch her in this video:

If you were unable to join us for the day, we strongly urge a visit to this very interesting complex. There is much more to learn about Watson’s Mill and Dickinson Square from their fact-filled website: Watson's Mill & Dickinson House

Grain Milling Process at Watson's Mill

Grain Milling Process at Watson's Mill

Having finished at the mill site, fifteen of us took the short walk to The Vault Bistro where we enjoyed a variety of fine dishes.

The weather smiled upon us and we all left Manotick with smiles ourselves.

Video and photos courtesy of Justin Lacasse.

Museum Club Visit to Merrickville

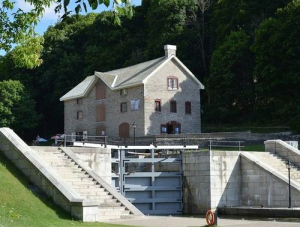

The third Museum Club outing took place on Thursday, July 18, 2024, when a dozen registered participants, and two “foundlings” received a guided tour of the Merrickville Blockhouse Museum from our host, Jane Graham, who is the President of the Merrickville & District Historical Society (MDHS). Jane explained that the Blockhouse was built in 1832 to defend the Rideau Canal but never served in its original role. Instead, it became the home of the first lockmaster, Sgt. Johnston, his wife and children. Over the years the Blockhouse has had many other uses including as a storage facility and a church. Eventually it fell into disrepair and was scheduled to be demolished in the early 1960s. It was saved by the community of Merrickville who raised funds and created the Merrickville & District Historical Society to restore and operate the Blockhouse. The work has since become more than the volunteers of the MDHS can realistically handle, so the Town of Merrickville has now assumed responsibility for the Blockhouse Museum.

After about an hour in the Blockhouse Museum, Jane led ten of us on a guided walking tour along the main street of Merrickville pointing out many of the historic buildings and telling us the stories behind each. Jane told us some of the details of the history of Merrickville itself, from its origin as a thriving industrial and commercial hub, through its decline into the mid twentieth century and its renaissance in the past few decades as a vibrant community and a haven for artists and artisans of all kinds. She also told us some colourful stories of a number of its more prominent early residents and of the plans of the MDHS to honour one of these, Harry McLean, with a statue. The weather was perfect for the walking tour and there was much to see and yet more that could be explored independently based on a walking tour guide that is available through their web site.

Following our walking tour, which lasted just over an hour, we said good bye to Jane and retreated to the Mainstreet Restaurant, across the street from the Blockhouse, where the ten of us were warmly greeted. The large menu offered many tasty choices and their own lager was enjoyed by a number of our party. After lunch, the group dispersed, some browsing, and buying, in Merrickville’s fascinating array of shops.

Museum Club provides an opportunity for its participants to make new connections or in some cases discover existing connections they did not know they already had. The latter occurred on our Merrickville trip when a casual lunchtime discussion revealed that one of the participants knew the grandparents of another, even though the two participants had never met and the grandparents live in south-western Ontario. As they both agreed, it is a small world.

One of the goals of the Museum Club is to strengthen the relationships between the Historical Society of Ottawa and other organisations involved in the exploration of our local history or in preservation and conservancy. To this end, a partnership is now being established between the HSO and the MDHS whereby the MDHS will send the HSO electronic copies of their newsletters and invitations to their speaker series presentations and the HSO will reciprocate, providing more opportunities for the members of both organizations.

A Local Canvas: Paintings from the Bytown Museum Collection

Bytown Museum's Collections and Exhibitions Manager, Grant Vogl, gives a snapshot of the vast collection of art works held within the museum's vault.

Bytown Museum’s Roots with the Historical Society of Ottawa

The guest speaker for the first HSO meeting of 2020 is familiar to many who have a love of Ottawa’s past. As the executive director of the Bytown Museum, Robin Etherington has been an enthusiastic promoter of culture and heritage in Ottawa for over 20 years. Robin has been the executive director of Bytown Museum since 2012.

The Bytown Museum is located in the oldest building in the city. Of course, the museum wasn’t built as a museum. The stone structure was initially a “commissariat” and its construction was supervised by none other than Lieutenant-Colonel John By.

Built as early as 1826 and located near the entrance lock of the Rideau Canal, today’s Bytown Museum initially served as the operational nerve centre during construction of the canal (the Commissariat Department of the British military oversaw the supply of food and provisions) and then as the administrative headquarters of the canal once it opened in May 1832.

Robin EtheringtonRobin noted that By was more than just a canal builder. He was as much an urban planner. He laid out the early streets of Lowertown and also what is now the Parliamentary Precinct. She also noted that By purchased land in Ottawa to reassure others that a thriving community would soon grow here.

Robin EtheringtonRobin noted that By was more than just a canal builder. He was as much an urban planner. He laid out the early streets of Lowertown and also what is now the Parliamentary Precinct. She also noted that By purchased land in Ottawa to reassure others that a thriving community would soon grow here.

After talking about the early days of the museum building, Robin discussed the formation of the organization that ran the Bytown Museum for 105 years. In 1898, thirty-one Ottawa ladies formed the Women’s Canadian Historical Society of Ottawa (WCHSO) to promote a better understanding of the city’s history.

The society was limited at the time to holding community meetings, but in 1917 an opportunity arose to expand the society’s scope. In 1910, the City of Ottawa had moved out of the registry office on Nicholas Street that it had occupied since 1871.

After the building was left vacant for seven years, the WCHSO proposed to establish a museum there to display artifacts that the ladies had collected over the years, with their own money.

In 1952, the Bytown Museum moved to its present location. In 1955, the men of Ottawa were invited to join the WCHSO. With the “W” now redundant, the name of the organization was changed in 1956 to the now-familiar Historical Society of Ottawa (HSO).

HSO continued to manage the museum and to hold regular meetings for members and the public until 2003, when the decision was made to transfer the Bytown Museum to a separate not-for-profit organization.

It was at this time that HSO “lost” its museum, but the association between HSO and Bytown Museum has remained strong. As such, Robin was less a “guest” speaker at our Jan. 15 meeting than she is friend, supporter and member of HSO.

Following her review of the history of the museum, Robin talked about something that is near and dear to her: the museum’s future. It’s not all good news. Being part of the Parliamentary Precinct’s independent, and rapidly aging power supply system, blackouts have become an all-too-frequent occurrence. Rockslides are a constant threat, as natural geological dynamics take a slow toll on Parliament Hill, which overlooks the museum.

Located near the bottom of a hill so steep that the lay of land forced Colonel By to build eight locks, universal accessibility to the museum has been an ongoing problem. And let’s not forget that the museum building itself will reach the beginning of its third century in 2026.

But there is a lot of good news, too. Robin observed that, “today is tomorrow’s history” and that was inspiration for Bytown Museum’s most recent exhibit, 100 Years of Youth in Ottawa.

This is a collection of photographs of young Ottawans from 1917 to 2017, showing how the many activities that youth have engaged in through the years have changed . . . and how many remain the same. All photos for the exhibit were selected and researched by the museum’s Youth Council.

New for 2020 is an exhibit entitled A Local Canvas: Paintings from the Bytown Museum Collection, in which the museum curates an eclectic assortment of paintings from an equally curious list of collectors and artists. The items chosen for the display were selected during the museum’s continuing project to capture digital images of its collection.

Burnstown Publishing.The last word for the evening went to Bruce MacGregor, who is author of Capital Recollections: A Baby Boomer Growing Up in Ottawa. Bruce has been a resident of Ottawa since 1952.

Burnstown Publishing.The last word for the evening went to Bruce MacGregor, who is author of Capital Recollections: A Baby Boomer Growing Up in Ottawa. Bruce has been a resident of Ottawa since 1952.

He taught English at Glebe Collegiate for 30 years. Capital Recollections is his first work of non-fiction. Bruce read an excerpt from his new book about a not-yet famous Canadian who happened to be at a local arena in 1963.

You’ll have to buy the book to find out who. It’s available for $20 via burnstownpublishing.com.

Victoria Memorial Museum

10 May 1901

At the end of Metcalfe Street between McLeod and Argyle Streets can be found the Canadian Museum of Nature, housed in a magnificent baronial building with beautiful stained glass windows. Constructed over a several-year period during the first decade of the twentieth century, the edifice’s official name is the Victoria Memorial Museum Building, in commemoration of Queen Victoria who died in January 1901. Within weeks of her death, the government chose to honour her reign by the construction of a museum.

On 10 May, 1901, a sum of $50,000 appeared in the supplementary estimates for the 1901-1902 fiscal year for the commencement of work on the Victoria Memorial Museum. After considerable debate, the appropriation was approved by the government of Sir Wilfrid Laurier, though the Conservative opposition complained about the lack of a definitive plan for the building. The government was also uncertain of its location. It favoured siting the building at Major’s Hill Park, with a bridge across the Rideau Canal connecting the Park to Parliament Hill, roughly where the Château Laurier Hotel is situated today. However, others thought Nepean Point might be a good location. Still others objected to both locations arguing that the land should be conserved for parklands. They preferred a location somewhere in the south of the city. Mr. Joseph Tarte, the Minister of Public Works, assured the House that no work would commence until he and his colleagues were convinced they had found the best design and the best site for the new building. To that end, he had sent David Ewart, the Chief Dominion Architect, to Europe to look into museum designs.

The site finally selected for the new museum was a property owned by the Stewart family a mile due south of Parliament Hill. Located there was a stone building called Appin Place surrounded by fields and gardens. Appin Place was a homestead that dated back to 1856, though actual construction of the house was delayed until 1862 owing to the death of the property’s owner, William Stewart, who had been the Member of Parliament for Bytown in the Province of Canada legislature. Appin Place, whose paddock was sometimes used as a cricket pitch, was a well-known landmark. It was surrounded by a massive cedar hedge that was noted for its beauty. The hedge had been transplanted from a nearby swamp during the 1840s. The house itself was built on the highest point of land in “Stewarton” in a direct line and level with the Centre Block on Parliament Hill. Appin Place was reportedly where Lord Dufferin had presented the colours to the Governor General’s Foot Guards in 1874. The government acquired the land for $73,500 at a sheriff’s sale in 1903 or early 1904.

Post Card of The Victoria Memorial Museum, before 1915

Post Card of The Victoria Memorial Museum, before 1915

Valentine & Sons’ Publishing C. Ltd, London, Toronto Public Library.The museum was designed by David Ewart, and built by George Goodwin of Ottawa. Goodwin had won the contract for building the museum with his bid of $950,000, excluding the cost of the electrical work, heating and furnishings. His was the lowest of four bids on the government contract. He would later come to rue winning the contract. The total cost of the building came to roughly $1,250,000, equivalent to more than $27 million in today’s money. Goodwin had previously worked on other public works projects, including the construction of the Trent Valley and Soulonges Canals. The new museum measured 430 feet by 169 feet with a tower 97 feet high. Its walls were built using Scottish work masonry in Nepean brown stone, with trimmings in Nova Scotia red stone. Credit Valley stone was also used. The four-story building was fire-proof with its floors made of porous terra-cotta covered with concrete. Wooden sleepers were set into the concrete to which wooden floors were fastened. The walls of the basement were lined with enamelled brick.

Demolition of the old stone Appin Place took only three days in mid-April 1905. Work on the foundation of the new museum commenced almost immediately. The structure was scheduled to take four years to build. But problems, disputes, and tragedy dogged the construction which took longer than expected. Goodwin wanted to substitute stone quarried in Ohio for the Nova Scotia stone, but was overruled by government; the contract called for Canadian stone throughout. In 1908, a labourer fell to his death while working on the building. He apparently lost his footing when he was 70 feet up on the girders. While he survived the fall, he sustained grievous injuries and died at St. Luke’s Hospital. By 1911, six stone cutters who had worked on the building had died from “stone cutters’ lung disease”—an illness, now called silicosis, caused by the inhalation of dust—that causes shortness of breath, cough, bluish skin, and ultimately death.

The name and organization of the new museum also proved to be controversial. A delegation of Ottawa’s finest, including Thomas Ahearn and Warren Soper (the partners who owned Ottawa’s electrical company and electric railway), J.R. Booth, the timber baron, and Erskine Henry Bronson, after whom Bronson Avenue was later named, appealed to the Prime Minister. They wanted the new museum to be called the National Museum of Canada that would report to a special government commission comparable to the British Museum in London and the National Museum in Washington D.C. Laurier promised to consult his Cabinet. The appeal failed.

As the building was finally nearing completion in early 1911, cracks began to appear in the front tower owing to settling. A slight separation was also noted between the tower and the main building. The Ottawa Evening Journal ominously noted that the contractor, George Goodwin, was the builder of the Laurier Tower, an addition to the West Block on Parliament Hill erected a few years earlier that had subsequently collapsed. Government engineers initially thought that the cracks in the museum would soon be remedied. However, they proved to be wrong. By late 1911, cracks had appeared on both sides of the entrance rotunda. Some were as much as five inches across. The cracks were plastered over several times, only to reappear. In late 1913, the Department of Public Works denied that it was considering dismantling the tower. However, by the summer of 1915, it became obvious something had to be done to ensure public safety. There was even talk of tearing down the entire building. In the end, engineers decided that while the building could be saved, the tower had to come down. It was simply too heavy to be supported by the foundation which rested on unstable clay. Goodwin, the builder, who reportedly lost a fortune on the building, died later that same year. It is said that he had tried to warn the government about problems with the building’s specifications but his concerns had been brushed aside.

Inside of the Victoria Memorial Museum, 1913

Inside of the Victoria Memorial Museum, 1913

Geological Survey of Canada/Library and Archives Canada, C-065507.Despite worries about its solidity, staff moved into the Victoria Memorial Museum in 1911 in order to get ready the many artifacts in the government collection. This included the Geological Survey’s collection of Canadian ores and minerals, fossils, stuffed mammals and birds, insects, as well as First Nations’ handicrafts, phonographic records of songs of Indigenous peoples, as well as antiquities and other objects of scientific value. The National Gallery of Canada, with its over four hundred paintings, sketches, etchings and sculptures, also moved into the Museum. In 1913, the Museum acquired a complete skeleton of a “duck-billed” dinosaur, of the family Trachodonatae, discovered in the Red River Valley of Alberta. According to the Ottawa Evening Journal, the fossil was three million years old. Today, this animal is known as a hadrosaur, the old name of Trachodon no longer being used. The fossil, which can still be seen at the Museum of Nature, is actually about 65 million years old.

When the museum first opened its doors to the general public is a bit murky. The National Gallery of Canada located in the Museum building opened in mid-May 1912, from 9 am – 5 pm Monday to Saturday. It is probable that the Geological Survey’s collection opened at the same time. Admission was free. Owing to the great popularity of the museum, opening hours were subsequently extended to Sunday afternoons despite opposition from some clergy.

When the Centre Block on Parliament Hill was gutted by fire in early 1916, the Victoria Memorial Museum was quickly fitted out as the temporary home of the Senate and House of Commons. The House of Commons was located in the lecture hall while the Senate was housed in the hall previously devoted to fossils and extinct animals, a fact that caused great hilarity. Some wags noted that little had changed. Parliament met at the museum until 1920. The previous year, the body of Sir Wilfrid Laurier had laid in state in the temporary House of Commons chamber.

Over its life of more than 100 years, the Victoria Memorial Museum building has undergone two major renovations. During the early 1970s, it was closed to allow for workmen to stabilize the building which was still sinking into the Ottawa clay that lay beneath it. In 2010, a major building renewal and renovation took place. A 65-foot glass tower was installed in the same location as the old tower that was torn down in 1915. It was unveiled by Queen Elizabeth in 2010 and is called the “Queen’s Lantern.”

Museum of Nature, Victoria Memorial Museum Building, 2017, Google Street View.

Museum of Nature, Victoria Memorial Museum Building, 2017, Google Street View.

Sources:

Canadian Museum of Nature, 2018. Historical Timeline.

Globe, 1912, “The National Art Gallery of Canada,” 4 May.

—————————–, 1915. “”Contractor Goodwin Dead,” 1 December.

—————————–, 1916. “Tempoarary House of Parliament,” 5 February.

Globe and Mail,” 2006. “New life for old bones,” 21 October.

Ottawa Evening Journal, 1904. “Commons And Ottawa Items,” 25 March.

————————–, 1904. “To Build Royal Victoria Museum,” 27 September.

————————–, 1905. “Number One Hard Wheat Threated by the States,” 10 February.

————————–, 1905. “Appin Place, Historic House, Will Disappear,” 4 March.

————————–, 1905. “Stewart Homestead A thing Of The Past,” 17 April.

————————–, 1906. “He Must Use The Canadian,” 2 May.

————————–, 1908. “Fatal Fall From Victoria Museum,” 16 June.

————————–, 1910. “Deputation on Change of Name,” 8 December.

————————–, 1911. “One Million And A Quarter Dollars of Estimates Passed,” 24 March.

————————-, 1911. “Cracks In Museum Wall Is Not Growing Larger,”21 April.

————————-, 1911. “Five Stone Workers Dead,” 8 May.

————————-, 1912. “Art Gallery To Open On Saturday,” 14 May.

————————-, 1913. “Dinossaur (sic) Is Secured For Museum,” 4 January.

————————-, 1913. “Museum Tower,” 2 October.

————————-, 1915. “Sealed Tenders for Partial Removal Of Tower,” 11 August.

————————-, 1915. “Contractor For Museum Warned Minister Plans Would Not Suit,” 12 August.

————————-, 1914. “Fine Skeleton Of Dinosaur At Victoria Museum,” 12 September.

Story written by James Powell, the author of the blog Today in Ottawa's History.

Retired from the Bank of Canada, James is the author or co-author of three books dealing with some aspect of Canadian history. These comprise: A History of the Canadian Dollar, 2005, Bank of Canada, The Bank of Canada of James Elliott Coyne: Challenges, Confrontation and Change,” 2009, Queen’s University Press, and with Jill Moxley, Faking It! A History of Counterfeiting in Canada, 2013, General Store Publishing House, Renfrew, Ontario. James is a Director of The Historical Society of Ottawa.